From the Archive: Paris by Pontiac Trans Am

From the January 1979 issue of Car and Driver.

It was [then–associate editor Mike] Knepper's idea. "Why don't you try to get a Trans Am to drive while you're in Europe?" he asked. Immediately, that sounded like a terrific idea. Pick it up at Frankfurt-Main airport, drive it to Austria, then Stuttgart, then Paris, then give it back. "Terrific!" said GM Overseas Public Relations, so we called the travel agent and made our low-buck Apex reservations, Detroit–Frankfurt. When it was too late to change, GMO called back and said, "Hey, terrific, you can pick the car up in Antwerp!" So a deal was struck. We borrowed a Porsche 928 for the first leg of our trip, then flew from Stuttgart to Brussels to collect our Trans Am.

We spent a lovely afternoon with the irrepressible Tony Lapine, chief designer for Porsche and resident sage at their growing Weissach facility. Then, with considerable regret, left him to race off into a 40-minute traffic jam that interposed itself 'twixt us and Flughafen Stuttgart, whence Sabena would transport us to beautiful Brussels and our waiting Firebird.

Belgium is not a fun place, especially when it's cold and foggy. Belgium is not very big, either, and the high density of the small nation's industrial plants means that you're never far from a smokestack or some dispirited village that depends on a local coal mine for survival. As a result, the Belgian man on the street looks like one of H.G. Wells's Morlocks.

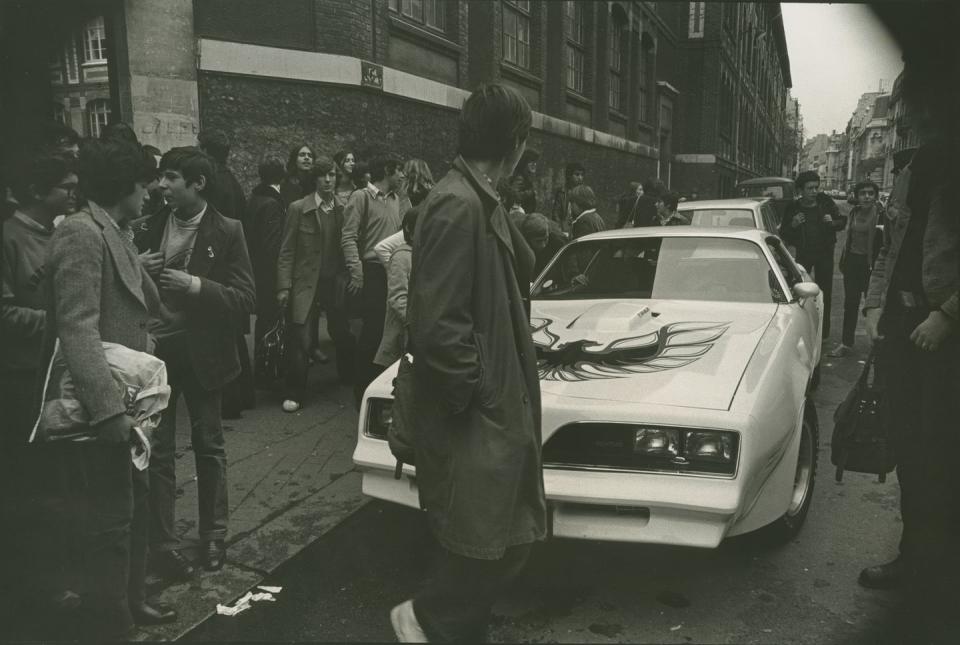

At Brussels, the customs guys waved us by without checking our luggage, but even so managed to convey the feeling that they recognized us as undesirable aliens, probably smugglers. Out on the sidewalk, I guarded the luggage while J.L.K. Davis went off in search of the Trans Am. I was watching Belgian cabdrivers jockey for position in front of the terminal, enjoying the near misses that occurred regularly, when a white Trans Am complete with screaming chicken decal and Chris Craft exhaust note came rumbling out of the maw of the parking lot, my wife at the helm.

The Pontiac Trans Am is one of the last—but surely the best—of the Sixties' silly cars. It is large for what it is supposed to do, claustrophobically small for whom and what it's supposed to carry. It still manages to look sexy, and Pontiac's enthusiast-engineers certainly seem to have found the secret of eternal youth and applied it to this clearly obsolete package, because a Trans Am is still a great kick, visually and dynamically, and that kick never came through as forcibly as when I saw our shiny white one shouldering its way through the Fiats, Renaults, and Citroëns in front of the Brussels airport.

If the customs people eyed our luggage suspiciously, the Trans Am was positively hostile about it. Pop the decklid. "Twit! You thought you'd get some luggage in here!" The specifications for this car say that it offers 6.6 cubic feet of luggage accommodation. This is true, but only if you're hauling loose sand. You could carry quite a lot of clothing back there, but only if you left the suitcases at home. We managed to get one duffel bag into the trunk, but the other four pieces had to be stacked on the back seat. Hah! "Seat," they call it, with considerable irony. It may look like a seat, but it is no place to sit.

It was disappointing to clamber inside and find an automatic-transmission selector lever instead of a four-speed manual, but otherwise it was predictably Pontiac—a little bit of home for two Americans who'd been away from the Big PX for 10 days. And after 10 days in a variety of Fiats, Porsches, and Citroëns, I unconsciously reached for the seat adjustments and was sharply brought back to another fact of American life: the non-adjustable seat (unless you count fore-and-aft). Maybe Nash wrecked it for all future generations of American car buyers . . . The cars from Kenosha came with reclining seats, not for driving but for sleeping, and this seemed to give reclining seats a bad name forever in the strait-laced American heartland. So there you are in America's premier road machine, bolt upright for want of a simple product feature that's been on German cars for 30 years, and standard equipment on even the meanest Japanese import. The front seats aren't necessarily bad, but it is a shame that the driver and passenger must adjust their bodies to the seats, and not the other way around.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos