Bill Simpson Lit Himself on Fire to Protect Racers Worldwide

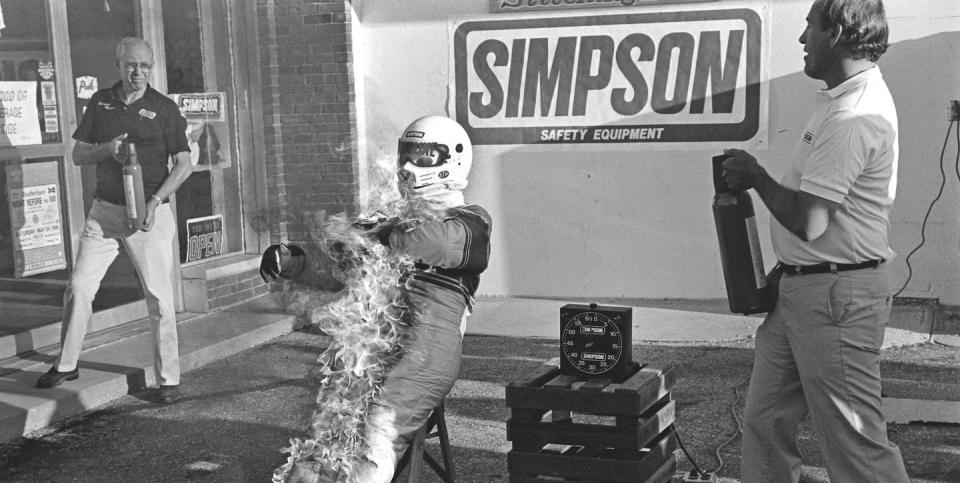

The ad that brought Bill Simpson to fame was a perfect visual for the man.

Set ablaze for a publicity stunt in the early Seventies while wearing his company’s flameproof racing gear, the safety pioneer, who died last December at 79, burned shades of bright red. Then the fire was put out. The colors matched his temperament. In that ad, the human torch sat inside Turn 1 at Indianapolis as waves of heat furled skyward. By demonstrating his willingness to be set alight inside the very Nomex he sold, Simpson launched his company to prominence. Simpson Racing Products stole the march within America’s burgeoning driver-safety market.

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Road & Track.

“If you ever did anything in racing where you had to put a helmet on, seatbelts on, a fire suit, shoes, gloves, fireproof underwear—at some point, he touched your life,” says three-time NASCAR champion Tony Stewart.

Simpson’s initial foray into safety-equipment manufacturing came at a time when the Southern California hot-rodding scene took a faster, scarier turn.

“I met Bill in the late Fifties,” says drag-racing legend Don Prudhomme, Simpson’s lifelong running buddy. “We were at Lions Drag Strip in Long Beach, and we were just thinking about putting parachutes on our drag cars because they were going… well, at the time we thought, really quick.

“We had drum brakes. Simpson had this idea of putting parachutes on the back to slow us down after we crossed the finish line. So I went over to his house, and he was stringing up parachutes out in his garage. I ran one of his very first parachutes, and that changed the sport completely.”

The sport would meet its greatest change in Simpson’s late-Sixties encounter with NASA astronaut Pete Conrad. The racing-mad Conrad introduced Simpson to Nomex, a new fire-retardant material used in spacesuits. Driver safety vaulted out of the Dark Ages.

“We were wearing jeans and a leather jacket driving these front-engine top fuel cars of the late Fifties,” Prudhomme adds. “He came up with an idea from the parachutes to do fire suits, and he had us all looking like spacemen. Had these silver suits, and they looked kind of corny, but they really worked good.

“I was in one of them and had a fire. It saved my ass. Then he started building fire suits for IndyCar guys, all sorts of stuff. But he really got his start with that and seatbelts in drag racing.”

Simpson’s mark on racing was also driven by trust. More than 50 Indy-car starts from 1968 to 1977, including one at the 1974 Indy 500, cemented his reputation as a fellow racer whose safety equipment performed. But despite being embraced by most drivers—all of whom saw value in his products—Simpson’s volatile personality was met with firm opposition by USAC, the sanctioning body in charge of the Indianapolis 500.

“USAC immediately hated him. Nobody [there] wanted to take him seriously, because he was this long haired, Fu-Manchu-mustache-wearing, dope-smoking hippie,” says celebrated IndyCar reporter Robin Miller. “But the younger guys that raced at Indy, Mario Andretti and Johnny Rutherford and guys like that, they at least cared about safety. Because we had no clue about anything safety-wise, and [drivers] were so unprotected.

“I mean, it took A.J. Foyt a while to accept it, but he was always the last guy to sign up. Bill was the very first guy that ever took safety seriously. Nobody thought about shit like that until he came along.”

Simpson’s creations, including his first racing helmets, took hold in North America throughout the Seventies. By the latter part of the decade, his name was seen in Formula 1 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans, but his market share enveloped Indianapolis.

“Lew Hinchman had been around forever, and most everybody wore his [company’s] fire suits until Bill started chipping away at that monopoly,” Miller says. “Then Simpson really started to take over. I think he had all but three of the 33 drivers in the ’77 Indy 500 wearing his suits. And it wasn’t that Hinchman suits weren’t good. It was just that Bill, he promoted himself, and you know… when you set yourself on fire to prove a point. Well, Lew wasn’t going to go that far.”

Facing a wave of opposition from new safety-apparel manufacturers by the mid-Eighties, Simpson went back to the well for headlines.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos