Breast cancer costs linger for many women as Medicare falls short

Devastated, tired and still in some pain after a mastectomy and radiation last fall, Jacqueline Abdelmeguid lives wondering how long it will take to regain her health. Hopefully it’s soon.

But she fears it will take her years to pay the medical bills that keep coming, perhaps for the rest of her life, just to make sure her breast cancer doesn’t return.

She holds up her phone and scrolls through her Corewell Health medical chart to show a note in cursive telling her: You owe $4,122.89.

“I skip over it real quickly because it makes me sad,” said Abdelmeguid, 65, who is on unpaid medical leave from her 30-year Postal Service job. She owes two months’ rent on the Oak Park home where she lives with her husband, a recent immigrant from Egypt, two daughters and her grandson, 15.

Medicare can fall short by thousands of dollars

Older women who, like Abdelmeguid, struggle with the financial burden from their breast cancer care, are a poorly recognized part of a serious American health care problem that leaves millions of Medicare recipients with out-of-pocket expenses that strain and even bankrupt them.

Many are shocked to find their Medicare insurance — including popular Part C and D plans — can leave them financially vulnerable for thousands of dollars in co-pays for medicines, doctor visits and hospitalization.

“Some people think, 'Oh, you’ve got Medicare. It’s a get-out-of-jail-free card.' But it’s not,” said Dr. Reshma Jagsi, an Emory University radiation oncologist among the first researchers to study financial problems among breast cancer patients, in a large study in 2014 in Detroit and Los Angeles.

More: 3.17 million Michiganders must reapply for Medicaid. Why it matters now.

More: U-M to begin prescription drug delivery by drone in 2024

Research about the burden of medical bills, known as financial toxicity, has focused mostly on people younger than 65, in part because they do not have the almost universal coverage that people 65 and older have through Medicare.

Only 1% of the U.S. population, some 350,000 who are 65 or older, have no Medicare coverage, including many undocumented immigrants. About 9% of Medicare’s 61 million current beneficiaries have only the barest of coverage, and are faced with large medical debts if they develop chronic problems requiring more doctor visits, prescription medicines and testing.

But a six-month investigation of older women with breast cancer, a project funded through three national organizations, found breast cancer patients with more comprehensive Medicare plans struggling to pay bills, relying on strained financial assistance programs.

Assistance programs can be spotty and burdensome

Help from hospitals and nonprofits may not be offered because doctors may never ask, and hospitals may not use screening tools and questionnaires to find out who needs help.

What help is available is scattered and even can dry up temporarily because some organizations run out of money and must put applicants on wait lists. With or without help from social workers, women scramble to assemble needed documents like tax returns and bank statements to apply for grants to help pay household or medical expenses, mortgages and costly prescription drugs. Others raise money through online platforms or events like church spaghetti dinners.

Left with tough choices to put food on the table, gas in the car or pay a medical bill, as many as 30% of patients do not fill a prescription for a cancer drug, according to an April 2022 study in the journal Health Affairs. Health care costs are the top cause of bankruptcy filings in the United States, as well as being the most common reason for online fundraisers.

Others go without food or skip medical appointments, compromising their health. Some decline unaffordable treatments that could be lifesaving.

Jane Monstrola, 69, of Irwin, Pennsylvania, said she would have told her daughter “I’m done’’ without outside help she received from fundraisers and advocacy groups.

“It was just co-pay after co-pay,” said Monstrola, who underwent chemotherapy and a double mastectomy in 2020. A mother of two, she hopes to return to her part-time, minimum wage job at a card shop that helps pay the family’s bills.

Breast cancer patients are particularly vulnerable to developing financial problems because they must undergo several types of treatment and years of follow-up, explained a Feb. 8 editorial for the Journal of the American Medical Association’s JAMA Online.

“Compared with other chronic conditions, patients with cancer are at risk for higher out-of-pocket expenses,” the editorial said. “Breast cancer care in particular may be associated with high financial toxicity given the need for screening and diagnosis, multidisciplinary care and longitudinal follow-up; notably gender affects financial security.”

Medicare's vital role for women

A Medicare debate unfolding in Congress about the nearly 50-year-old program is particularly important to women, who outlive men and account for 54% of Medicare’s 61 million recipients. The program’s enrollment will grow to 80 million older or disabled adults by 2030.

Breast cancer, the most common tumor in American women, also is a disease of aging. One in 5 women 70 and older get breast cancer, compared with 1 in 43 for women ages 40-50.

For these older women, Medicare is a lifeline. They often don’t have health and pension benefits as good as men’s plans. Retirement benefits may be smaller because they moved in and out of the paid workforce, raising families and serving as family caregivers. Others worked in part-time, lower-paying jobs without benefits or never had a life partner with benefits upon the partner’s death.

As potential congressional debate on Medicare looms, the White House already has issued several statements advocating changes to lower Medicare out-of-pocket costs, as well as the opposition it expects from Republicans.

Medicare always has had noticeable gaps and shortfalls, and often has been considered less generous in coverage than employer-sponsored insurance, said Marianne Udow-Phillips, a University of Michigan health insurance expert and former executive at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

High-deductible plans can lead to big bills

The average Medicare beneficiary spent $3,024 on out-of-pocket costs in 2017, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund, a New York health advocacy foundation. A cancer diagnosis can bring even greater financial challenges, with some drugs costing $20,000 or more a year.

High-deductible plans requiring policyholders to first pay set amounts, starting every Jan. 1, before their insurance begins to cover care, also contribute greatly to out-of-pocket spending on health. These plans are particularly popular among younger people, but older ones bought them for the same reason: They were willing to take a chance they wouldn’t get sick in exchange for a low monthly premium.

More: Doctor disciplined in 7 states for medical errors still practicing in Michigan

More: Maternal mortality jumped 35% during pandemic's 1st 9 months, MSU study shows

The Internal Revenue Service, which sets limits each year on what insurers can charge, defines a high-deductible plan as one beginning at $1,500 for a person to $3,000 for a family, though a plan can require some policyholders to pay deductibles as much as $7,500 for a single person and $15,000 for a family in total yearly out-of-pocket costs.

Spending even $1,000-$2,000 can cause worry and sacrifice, along with a reduced quality of life and lower satisfaction with cancer care, says the American Cancer Society. A 2019 Federal Reserve Board analysis reported that 40% of Americans do not have $400 in the bank.

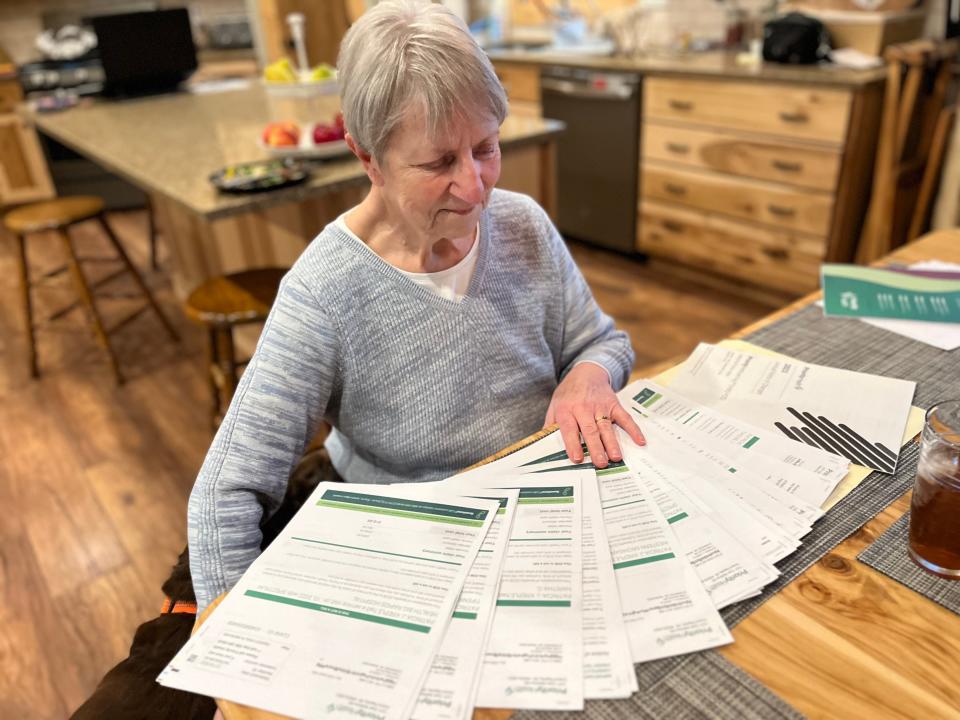

Pat Kreple, 76, a mother of three from Stanwood, near Big Rapids, typically a rock in her family, admits she “freaked out’’ when she got a bill “on the three-week anniversary of my mastectomy last November.”

“I couldn’t sleep at night. I mean, I would lie awake and go, oh, my gosh, we’re going to have to put this on credit cards. How are we ever going to pay this off?”

She reluctantly accepted gas money and a mortgage payment from her kids. “You never want to ask for help, but I had no choice,” said Kreple, a caregiver for her husband, a retired truck driver with early-stage dementia.

Kreple found an ally in a hospital social worker at Corewell Hospital in Grand Rapids, who insisted she notify her about any financial need that arose. She told her about several programs and helped her apply for them, including a $500 Meijer grocery card from the New Day Foundation in Rochester Hills. “Holy cow, we almost spent the entire thing in one day,” Kreple said. “We need food, toilet paper, shampoo, everything.”

Marilyn Collins, 68, of Waterford, considers the financial stress she faced after her February 2022 breast cancer diagnosis to be “very comparable" to the shock of learning she had an aggressive form breast cancer. She finally returned to work this February at a Waterford Buick dealership, where she is a customer service coordinator, because she developed an infection from a painful skin problem following surgery.

As her bills mounted, she went online and found various patient assistance funds, including the Pink Fund, a Southfield nonprofit that gives up to $3,000 to pay nonmedical bills of people during their breast cancer treatment. It helped Collins pay bills for three months, bringing her immense relief. A McLaren Oakland Hospital social worker in Pontiac helped further and gave her the name of an affiliated Karmanos Cancer Institute financial counselor who took the time to come to her home to talk to her and her daughter.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos