Paul Goldsmith Dies at 98: NASCAR Cup Race Winner Could Do It All

Editor's Note: Paul Goldsmith, whose racing career was spread across several disciplines, died at the age of 98 on September 6, 2024.

A member of several racing halls of fame and saluted by many of his contemporaries as one of the best all-around drivers in racing history, Goldsmith found success on four wheels and two.

A nationally-known star in motorcycle racing in the early 1950s, Goldsmith, with the considerable help of mechanic/crew chief/racing guru Smokey Yunick, transitioned to stock cars and became one of NASCAR’s finest. He raced in the Cup Series from 1956 to 1969, scoring nine wins and 44 top fives despite running only partial schedules. He and engineer/team owner Ray Nichels, a 2021 Motorsports Hall of Fame of America inductee, were a dynamic duo for part of that period.

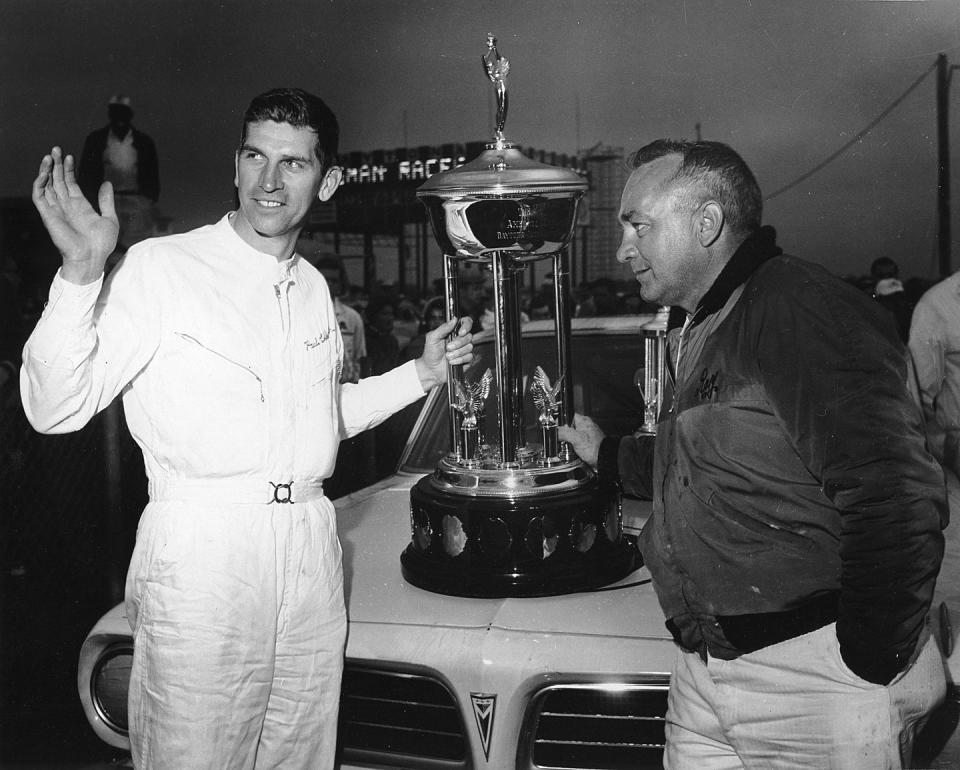

Goldsmith’s most notable NASCAR achievement will keep his name in stock car racing record books forever. He won the final race on the famous Daytona Beach, Fla. beach-road course, steering a Yunick-owned Pontiac to a five-car-length win in 1958. A year later, Daytona International Speedway opened a few miles from the shoreline, and the beach-road course, which combined racing on the Atlantic sand with the parallel two-lane paved highway, lost to the tide of the times.

As with several other race locations, Goldsmith used experience racing motorcycles to help navigate the difficulties of the Daytona beach-road course. Goldsmith also had won on motorcycles on the course.

The same dynamic helped Goldsmith score his first Cup victory Sept. 23, 1956 at the storied Langhorne Speedway in Pennsylvania. Known as the Track That Ate The Heroes, Langhorne was one of the most dangerous speedways in the country. At least 23 competitors died in accidents on the near-circular one-mile track.

A lead driver for Harley-Davidson, Goldsmith won at Langhorne in 1953, one of the highlights of a motorcycle racing career that would earn him entry into the American Motorcyclist Association Hall of Fame.

Three years later, Goldsmith returned to Langhorne in a stock car and used his mental blueprint of the track to win in NASCAR for the first time, outdistancing series veteran Lee Petty by an embarrassing seven laps. He led 182 of the 300 laps.

“It was a terrible track,” said Goldsmith, echoing the opinions of many drivers who ran Langhorne. “It was mainly about the kind of surface it was. Some of it was deep, some of it shallow. It was a lot of work, but I didn’t have much trouble. I could run just about wide open around the track because I knew where to go. I knew where the bumps were and where the surface changed.”

The race was a grueling affair, 300 laps around the wicked Langhorne circle. Twenty-four of the 44 starters failed to finish the race, and the fifth-place finisher, Herb Thomas, was a full 10 laps behind. Few were surprised at the power of the track to decimate the field. Driver Cotton Owens said racing at Langhorne was like “jumping a fresh-plowed field.”

The race was entertaining, however, particularly as Goldsmith and emerging star Fireball Roberts, who would win five times that season, exchanged the lead over a tense series of laps. Roberts’ challenge to Goldsmith ended, however, when he parked his Ford with a broken oil line.

The Langhorne win came in Goldsmith’s eighth NASCAR race and made him the first competitor to take checkered flags there in motorcycle and stock car events.

Yunick had been Goldsmith’s “agent” as he shifted from two wheels to four.

“I met Smokey racing motorcycles on the beach at Daytona,” Goldsmith said, remembering the moment 65 years later. “He saw me running (on the sand) and came over and said, ‘Why don’t we take your motorcycle out on this highway and so some things to it and make it go a little faster?’ We went out there on a back road, and I ran with another bike. I could stay even with him. We kept tinkering with mine, changing different things over a four-day period, and pretty soon I outran the other bike pretty bad. That helped me win the 200-mile bike race on the beach.”

Yunick, a mechanical genius who also had a good eye for talented drivers, pushed Goldsmith into stock cars, and they returned to the beach and the tough 4.1-mile test with four wheels.

“It was difficult to get a car set up for both the beach and the highway,” Goldsmith said. “And the highway was rough. The car wouldn’t handle unless you had the right suspension. Smokey helped me with that quite a bit. We went out on a back road there about four miles north of Daytona and worked on different shocks, tire pressures and suspensions. That’s where we learned how to do it. And I had raced motorcycles there, so that helped.”

Goldsmith outran Curtis Turner, the driver he later would classify as the toughest to beat, to win the beach-road course finale in a Pontiac carrying sponsorship from Yunick’s famous “Best Damn Garage in Town.”

Goldsmith won once in Cup in 1956, four times in 1957, once in 1958 and three times in 1966, his best season.

By the time Goldsmith, who also raced at Indianapolis Motor Speedway and in USAC stock cars, retired from competition in 1969 to concentrate on business interests, his home and office were filled with trophies from a spectrum of racing disciplines, including, oddly, one for a brief foray into harness racing.

At 95 years old (he turns 96 on Oct. 2), Goldsmith remains active. His office at the Griffith-Merrillville (Ind.) Airport (which he owns) contains some racing memorabilia, but his trophies were scattered to the winds over the years, some going to friends and relatives. “I had a truckload in here,” he said. “I had to get rid of them.”

But wait … there’s more

• Goldsmith’s worst racing injury occurred during his motorcycle career. In a race at a track near Cleveland, he ran his bike into a fence to avoid hitting another rider. He slid off the track banking and into race traffic. A following driver ran across his feet, breaking both.

• Goldsmith, born Oct. 2, 1925, had been the oldest surviving winner of a Cup Series race.

• Goldsmith probably could have challenged for a Cup championship, but he never ran anything close to a full season. He finished fifth in points in 1966 despite running only 21 of the 49 races.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos