After 40 Years, Vincent Chin’s Death Remains Deeply Troubling

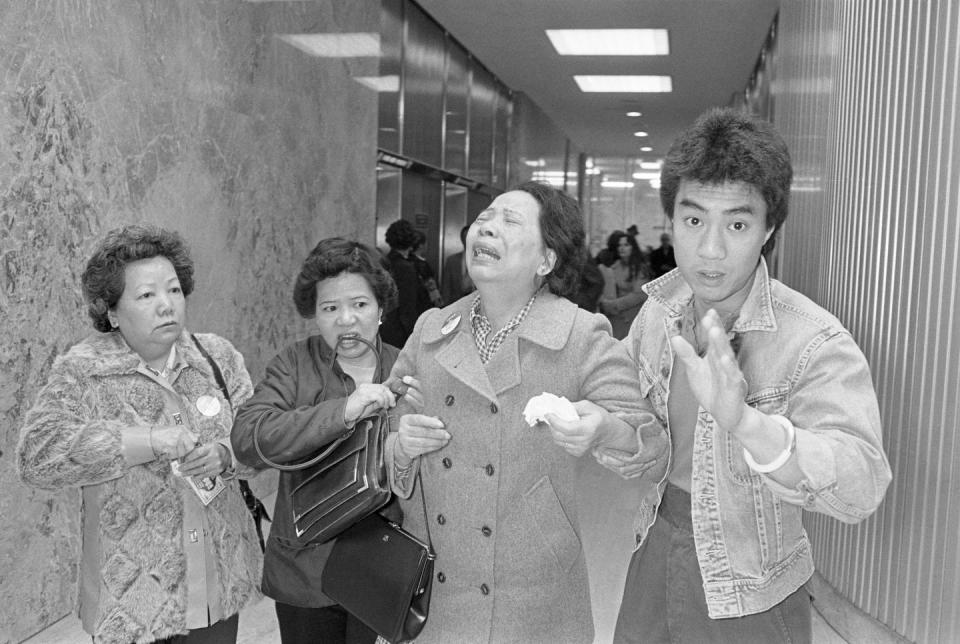

The killers pled guilty to manslaughter and—even more shocking than the crime—they got probation instead of jail time.

UAW member Sandra Engle calls on the union to confront bigotry in strengthening union values and because the union was founded decades ago on an urgent need for justice and fairness for all.

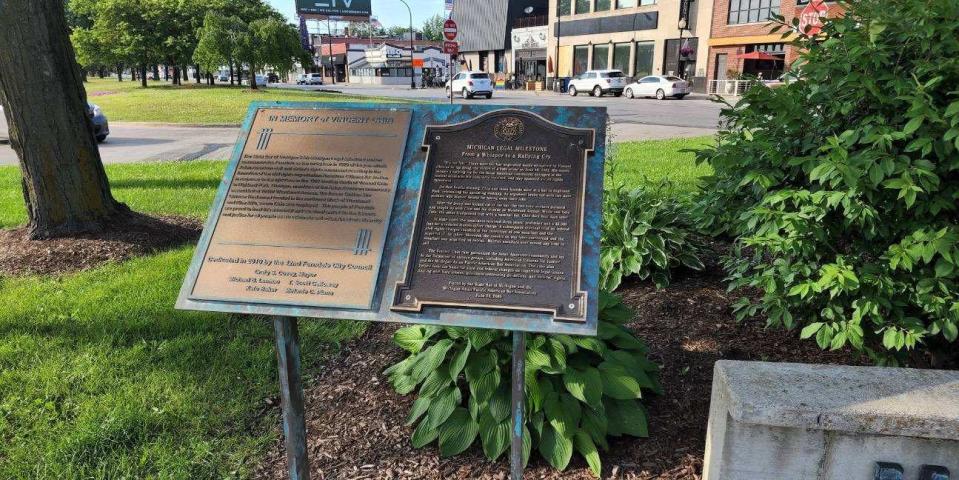

Hatred and racism have not abated since the death of Vincent Chin. (Above, a plaque dedicated to Chin in Ferndale, Michigan, four miles from the scene of the crime.)

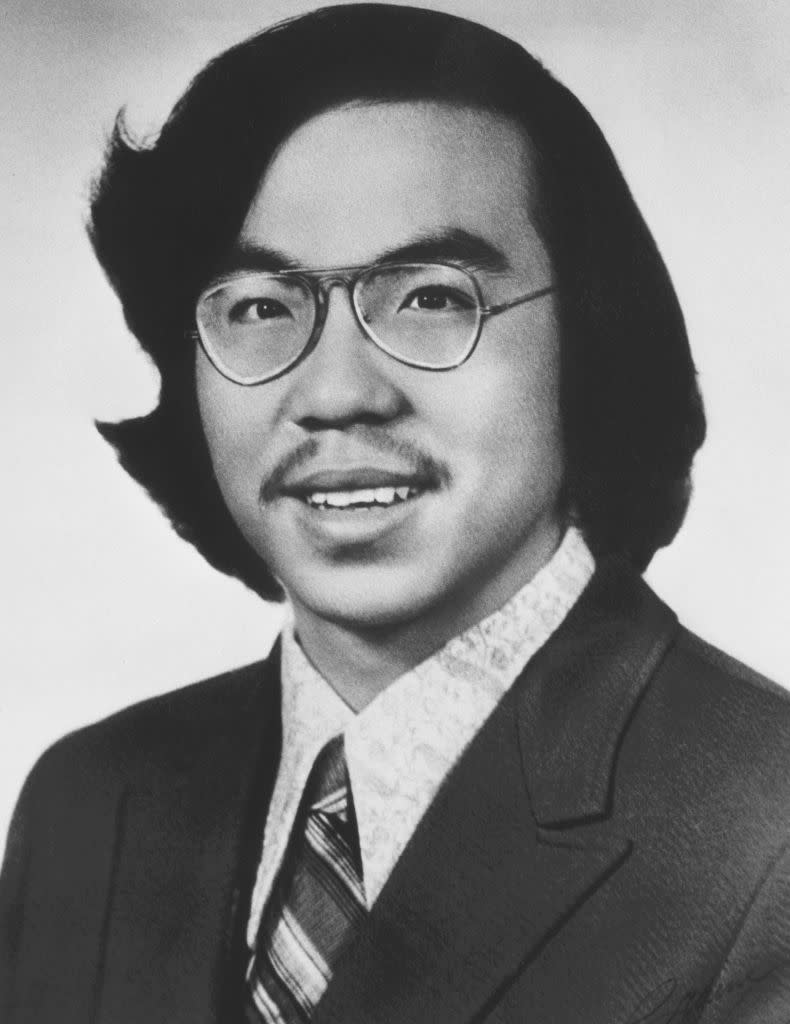

Forty years ago today, Vincent Chin was beaten to death with a baseball bat outside a strip club in Highland Park, Michigan, by two disgruntled auto workers—Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens, 43, and his laid-off stepson Michael Nitz, 22, a member of the United Auto Workers union.

Chin represented to them the reason why American automotive jobs were disappearing. He was Chinese, but they believed he was Japanese on that spring day in 1982 when the US was enforcing quotas directed largely at Japanese imported cars. Later that year, a Honda Accord would become the first Japanese automobile to roll off a US assembly line in Marysville, Ohio—the start of a trend of “foreign” cars built on American soil that continues today.

Inside the strip club 40 years ago, Ebens was eager to share his frustration and economic insecurity with Chin, a stranger who was there with friends for his bachelor party. Ebens was heard shouting at Chin: “It’s because of you little m—f—s that we’re out of work.” When Chin left the bar, Ebens and Nitz pursued him, found him outside a McDonald’s, and beat him savagely. He died four days later. The killers pled guilty to manslaughter and—even more shocking than the crime—they got probation instead of jail time.

Since the death of Vincent Chin, the US auto industry has grown much more diverse and global. And today the union recognizes that even before Vincent Chin’s death, there were signs that anti-Asian bigotry in Detroit was reaching dangerous proportions.

“Some auto plant walls displayed graphics featuring stereotyped buck-toothed Japanese taking American jobs,” UAW member Sandra Engle writes in a lengthy article posted May 26 on the UAW website. Racial slurs directed at Asians flowed freely on shop floors. “These were not closeted acts of bigotry—they were displayed proudly at Labor Day parades and on T-shirts worn to UAW events,” Engle writes.

At the time, Detroit automakers General Motors, Ford, and then-Chrysler ruled the market, but the next 20 years would see foreign automakers from Japan, Germany, and Korea set up assembly plants to build cars for America, in America, with American labor. Because of those foreign investments, tens of thousands of jobs were created in places like Marysville, Ohio; Smyrna, Tennessee; Georgetown, Kentucky; and Tuscaloosa, Alabama. UAW leaders have tried repeatedly to organize these transplant facilities, with no luck. Along the way, UAW membership has withered, from more than 1 million when Vincent Chin died in 1982 to fewer than 400,000 today. Retirement and health-care benefits are not what they used to be, and a contract negotiated in 2007 created a new starting pay of $14.50 an hour, much lower than pay rates for senior employees.

Today’s UAW jobs are are not the gravy they were perceived to be in 1982, and the union continues struggling to win back concessions granted to Detroit automakers when General Motors and Chrysler landed in bankruptcy in 2009. Harsh economic realities continue hitting us all—at the gas pump, on the assembly line, in the white-collar engineering labs, in the migrant farm fields. It seems no job is safe, whether there’s a pandemic ravaging the economy or not. Vincent Chin died because of racism and because change can be frightening, infuriating, and—to some—unacceptable. But his murder failed to alter the course of an American auto industry facing extreme upheaval.

In her article, Engle calls on the union to confront bigotry as an important part of strengthening union values and because the union’s founding was based on an urgent need to seek justice and fairness for all. “We must ask ourselves how this happened. We need to acknowledge that we failed to speak out against the vilification of a people,” she writes. “It is a conversation long overdue and timely today. The voices of the Black Lives Matter movement are demanding truth and reconciliation with such a fervent urgency that the status quo of yesterday cannot remain.”

A year before Chin's death, I remember being at a church fair in suburban Detroit and watching a long line of angry people pay $1 to swing a sledgehammer as hard as they could at a Japanese car. Those people were having a great time, and I recall these slam-fests happening across metro Detroit. I never imagined that such rage could be directed at a fellow human being. To think that two autoworkers would see their livelihoods so threatened that they would take the life of a young man purely because of his appearance was something a carefree high-school kid like me could not grasp—and still can’t. Also impossible to grasp was the sentence meted out in the name of "justice."

Hatred and racism have not abated since the death of Vincent Chin. In reality, the

problem is much worse now, demonstrated by so many tragic events in recent times.

That’s why the death of Vincent Chin remains relevant after 40 years—and why we

insist on remembering him today.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos