Bernie Ecclestone interview: ‘People don't go to F1 for a lecture from the drivers’

Gstaad is the lair of the billionaire, a little Alpine nirvana so saturated with wealth that even the prices for fondue are faintly heartbreaking. The ornate wooden chalets lining the central promenade bear the insignia of global haute couture: Louis Vuitton, Ralph Lauren, Prada, Chopard. Only one, Hotel Olden, still seems authentically Swiss, with its hand-painted facade, vibrant window boxes and history of resident yodellers. It is here that Bernie Ecclestone suggests meeting at 11.30am. The choice is less sentimental than practical. After all, he owns the place.

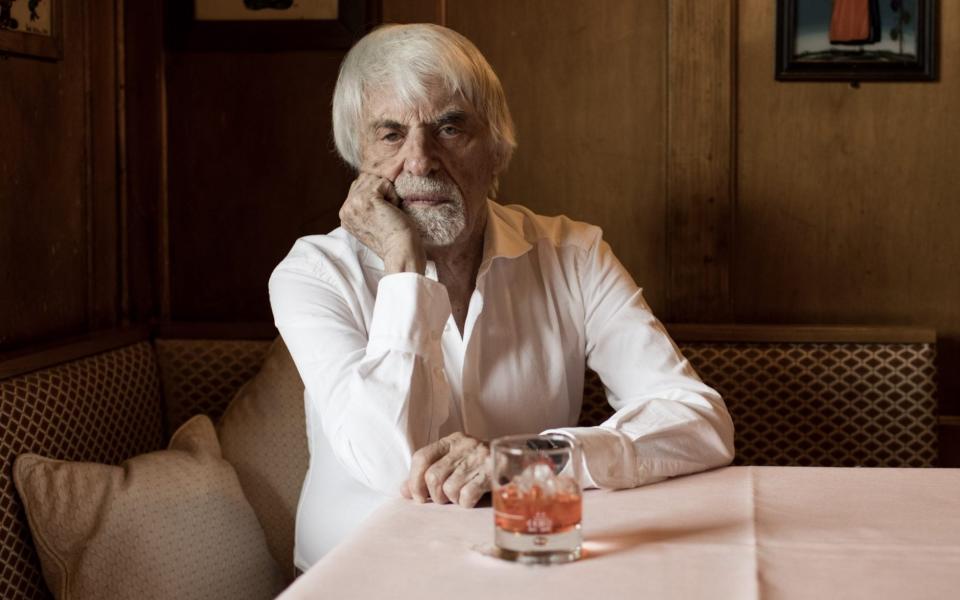

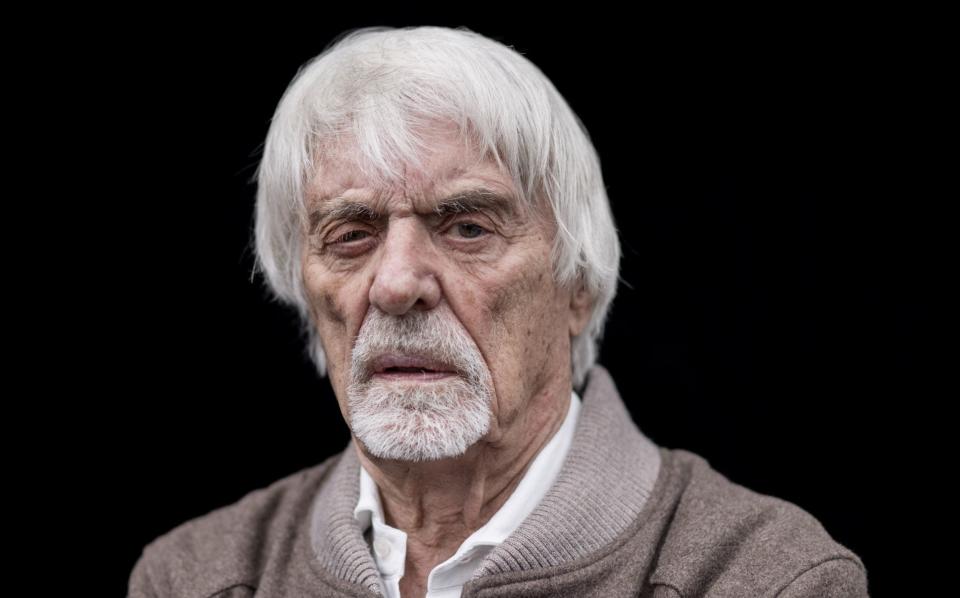

The management move to high alert at the news “Mr E” is en route. Furnishings are inspected, places laid, potential backdrops for the photoshoot mapped out. Half an hour early, an unmistakeable, snowy-haired figure materialises at the door. “Just got to see someone first,” he tells me, with a roguish grin. Ecclestone, the consummate dealmaker, is always seeing someone. “He never, ever stops,” says Jovan, his travelling household manager. Quite the tribute, all told, for a 92-year-old.

We take our seats, eventually, in the conservatory, a perfect spot for people-watching. Every few minutes, in a kitschy touch to seduce the jet set, a horse-drawn sleigh rolls past. “All part of the act,” Ecclestone says. And he should know, after half a lifetime spent transforming Formula One into the ultimate expression of money-no-object decadence. On Sunday, the circus rumbles into life once more, in Bahrain, and he intends to be there. He might not be the ringmaster any longer, but he is a close friend of the kingdom’s ruling family, the Al-Khalifa.

Sport will never see another like him, and he knows it. “It’s like Frank Sinatra singing. You’re not going to find another Sinatra. You see the guy who used to run football?” Who, Sepp Blatter? “Mm. He was a bit special, with the way he ran things.” But people did accuse him of being dictatorial, I point out. The same charge has repeatedly been levelled at Ecclestone.

“You see, I’m not somebody who’s super-enthusiastic about democracy. By definition, it can’t work. Look at England, the politics is 50-50, so which one is right? We’ve got to follow this or follow that. That’s what democracy is. It’s the wrong word, ‘dictator’. You need to have a boss. I always say, when I’m doing business with people, I want to deal with the people who can turn the lights on and off. I don’t want someone who has to make a report or get other people’s opinions before making a decision.”

Ecclestone, in tinted glasses and a beige fleece jacket over a white shirt, looks remarkably fit for a man in his tenth decade. And there is no doubt that he conveys, even at 5ft 3in, a strikingly godfather-like authority. Especially when his mobile phone rings with Ennio Morricone’s theme music for The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

Since he was dethroned as F1’s chief executive in 2017, his my-way-or-the-highway philosophy has been conspicuous by its absence. During his era, it was only Hollywood A-listers or European royalty who would be granted pre-race grid access. Today, it is such a cavalcade of rappers, Instagram influencers and assorted hangers-on that at one recent grand prix in Texas, Martin Brundle found himself barged aside by Megan Thee Stallion’s bodyguard. “Let’s put it this way,” he says. “If I were still there, I wouldn’t be doing a lot of the things that they’ve done.”

One habit on which he would crack down is the new-found fondness among drivers for making political statements. Barely a race goes by without somebody accentuating a grievance or a cause: it could be Lewis Hamilton wearing a rainbow helmet in Qatar to promote LGBT rights, or an “Arrest the Cops” T-shirt at Mugello to highlight the case of Breonna Taylor, the Kentucky medical worker shot dead by seven police officers in March 2020. Or it might be Sebastian Vettel peeling off his overalls to reveal a “Same Love” message, criticising Viktor Orban’s restrictions on the teaching of homosexuality in Hungarian schools.

“People don’t go to a Formula One race to have a lecture,” Ecclestone says. “Definitely drivers should have free speech, but it’s a case of when and how they use it.” With the outbreak of T-shirt activism, he clearly feels that a line has been crossed. “It’s wrong. It’s all completely wrong. I’m 100 per cent against it.”

The world governing body, the FIA, is with him, urging drivers to go easy on the political tub-thumping this year. Except Hamilton, in particular, appears in no mood to listen, least of all to Ecclestone. Last summer, Ecclestone suggested that he should “brush aside” a racial slur about him by former world champion Nelson Piquet, prompting this withering rebuke: “I don’t know why we are continuing to give these older voices a platform.”

Ecclestone bristles at Hamilton’s scorn of him as an “older voice”. “Maybe the older generation are not interested in listening to what he has to say. In general, the older generation have seen a lot more, done a lot more.” Warming to his subject, he even suggests that Hamilton was just sore at losing publicity. “Maybe, when the older generation are making statements, and some people think they’re correct, he doesn’t like it, because it’s taking up the space that he would normally have.”

You can understand his soreness. Contrary to popular perception, F1’s ascent to the realm of Netflix soap opera did not start with Hamilton. It began with a Warren Street second-hand car dealer called Bernard Charles Ecclestone, who engineered the astonishing coup to exploit F1’s commercial rights for 100 years and set about turning it into an impossibly ritzy, multi-billion-pound industry. Would Hamilton have so many accoutrements – the Colorado mansion, the garage of supercars, the Tommy Hilfiger fashion line – without him?

Ecclestone’s career constitutes one of the great sporting tapestries. Having left school at the age of 16, he supplemented his income by selling spare motorcycle parts. His talents as a wheeler-dealer were such that the supplier business he built, Compton & Ecclestone, became the largest in Britain. He would replicate this alchemist’s touch in F1, buying the Brabham team for £100,000 in 1972 and selling it for 40 times that amount 15 years later. The formula for prosperity and fame was gloriously simple. But in 2023, he admits to being bewildered by the world he inhabits.

“So many things in the world have changed,” Ecclestone says. “And the older generation can remember the changes. For the younger generation, it’s not the things from the past that they want to remember. People now have much more freedom to be heard. It’s all this telephone business. You or I could put something on the phone now and it would be seen worldwide.”

And is that dangerous? “Most people can’t make up their minds about anything. The danger is that they read something that somebody’s written, and they hang on to it. These people are called politicians. I wonder, with all politicians, whether they are genuinely sincere in what they’re saying. Ask them whether, before they got into positions of power, their views were the same. People are influenced an awful lot by others. They think, ‘If I say that, it’ll upset somebody.’”

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos