How a Device Invented In the 1860s Makes for Better-Sounding Porsches

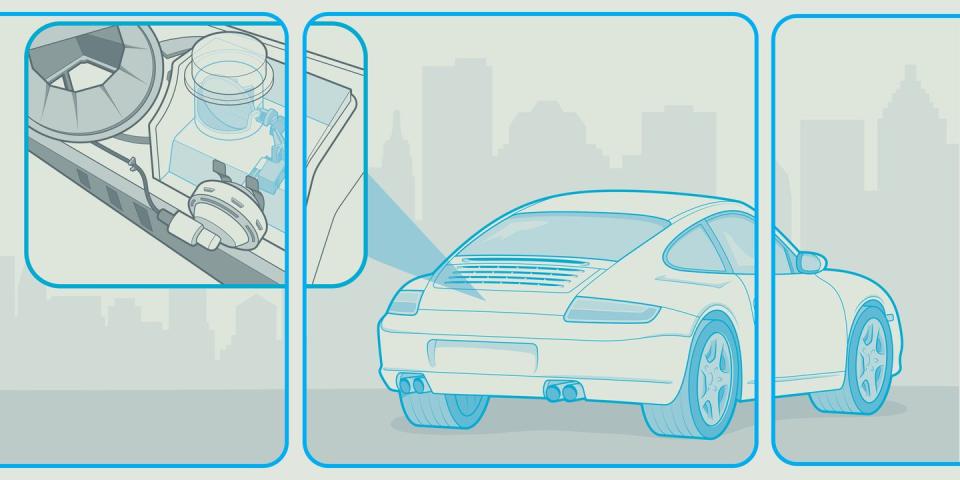

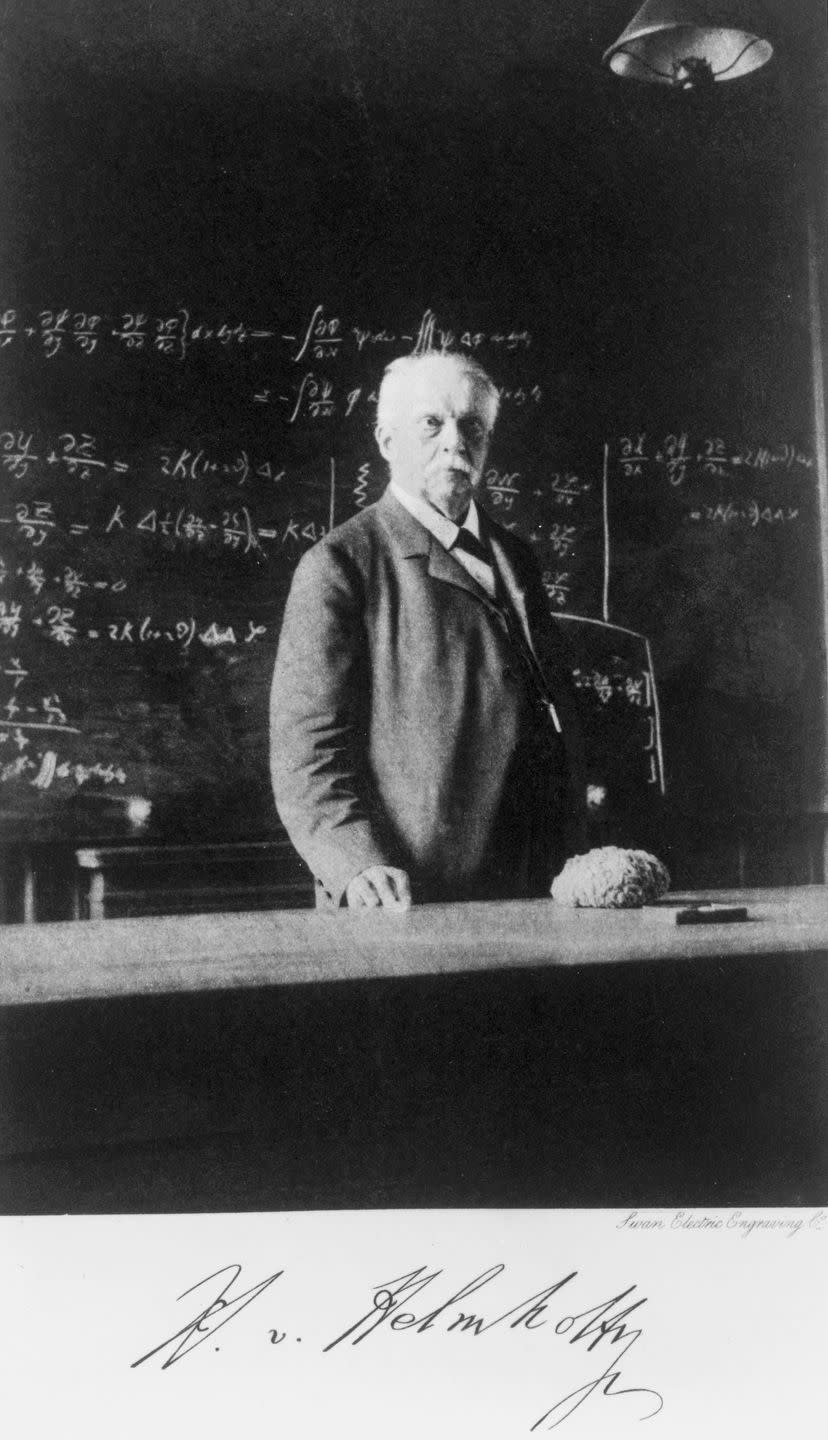

In either the 1850s or 1860s, German physicist Hermann von Helmholz created a device to analyze sound. In 2005, that same sort of device made its way into the airbox of the new 3.8-liter flat-six of the Porsche 911 Carrera S. The reasons why are fascinating.

We must start with a discussion of sound. In essence, sounds are just pressure waves that vibrate our eardrums. The frequency of the oscillation, measured in hertz, defines the sound's pitch. Most sounds, however, are not just one pitch. Strike a note on a piano, and you hear the primary note, a fundamental, plus a number of other, much quieter notes. These other pitches are part of what's called the overtone (or harmonic) series, and the volume of each overtone is what defines the quality, or timbre, of the sound. It's one of the primary reasons the same note played on a piano and an electric guitar sound so different. (A sound made up of just one pitch is a sine wave.)

Helmholtz wanted to analyze the makeup of sounds, so he created small brass spheres that resonate at a certain frequency when air is blown over the top. We now call these Helmholtz resonators. The volume of the air within the sphere determines the pitch at which the sphere resonates. It's basically a fancy version of what happens when you blow over the top a glass bottle. The amount of liquid in the bottle, which determines the volume of air, defines the pitch.

Strike a piano key and hold up a Helmholtz resonator of a specific certain size—and thus, pitch—to your ear, and if it resonates sympathetically, you now know at least one of the overtones that defines the timbre. It's a laborious and inexact method, but it was critical in furthering our understanding of sound. And a number of decades after their inventions some clever automotive engineers realized that Helmholtz resonators held interesting potential for internal-combustion engines.

But before we get to cars, we have to stay on the physics of sound, specifically the phenomenon of phase cancellation. In recorded audio, when two sounds of the same frequency but opposite amplitude are made at the same time, they effectively cancel eachother out, resulting in silence, or near-silence. Noise-canceling headphones use this phenomenon to drown out anything unpleasant. Microphones on the headphones pick up the sounds occurring in the environment, and play those same frequencies at the opposite amplitude in your ears. You can do the same sort of thing with a Helmholtz resonator. (And here, when we talk about a "Helmholtz resonator," we're not talking specifically about the brass spheres created by the German physicist, but a device of any shape that serves the same function.)

A patent filed by General Motors engineer Ernest E Willson in 1930 (seen above) describes a device consisting of multiple Helmholtz-type resonators—though he doesn't label them as such—to attenuate undesirable induction noise in internal-combustion engines. By tuning the resonators to resonate at the same frequency as certain tones created by the intake, you can effectively cancel them out, or at least make them much quieter. He updated his design, as detailed in a 1936 patent, with a device of variable volume that can be used in both the intake and exhaust systems of cars. Also in that patent, he notes his earlier design was "now commonly used."

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos