Here's Why the Cosworth DFV Is One of Racing's Greatest Engines

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

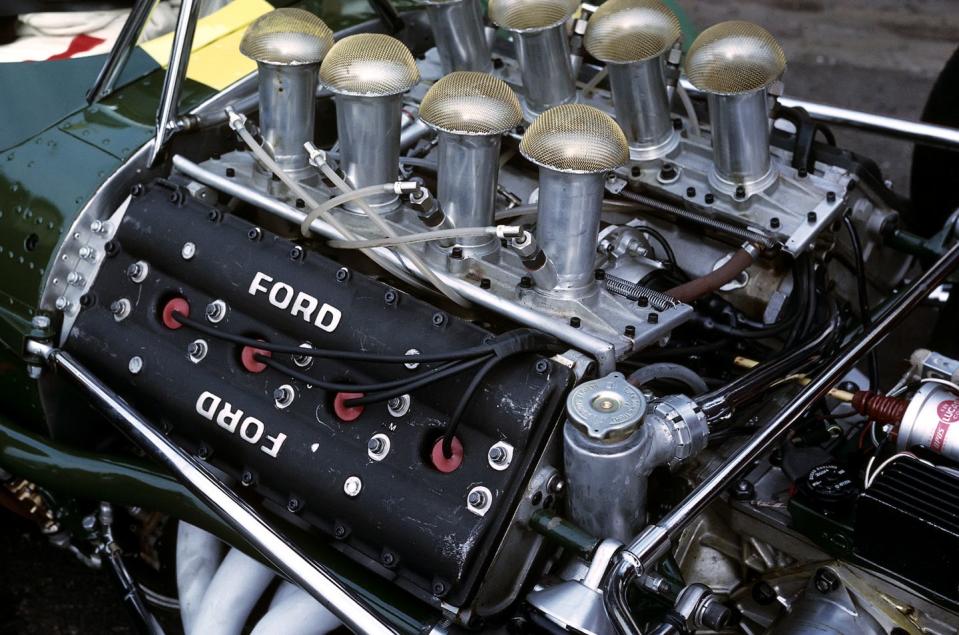

It might be impossible to name the greatest racing engine of all time, but the Cosworth DFV certainly makes a case for itself. Introduced in 1967 bolted to the monocoque of a Lotus 49, the DFV, a 3.0-liter V-8, racked up 155 Formula 1 victories over a period of 16 years, and powered 12 driver's titles and 10 constructor's titles. Turbocharged, it dominated IndyCar, with 10 Indy 500 victories in a row. It even won Le Mans in 1975 and 1980. No other race engine has quite an illustrious resume.

Grand Prix Ford: Ford, Cosworth and the DFV

$32.99

amazon.com

To understand why, we must talk about its designer, Keith Duckworth. After graduating with an engineering degree, Duckworth took a job with Lotus that lasted all of eight months because he didn't get along with founder Colin Chapman. Per Graham Robson's Grand Prix Ford, Duckworth yelled at Chapman for two-and-a-half hours upon quitting, then went and started Cosworth. Duckworth intended to run the business with good friend and colleague Mike Costin, but Costin was contracted to spend a few more years at Lotus.

Despite the blowout, Duckworth and Chapman retained a good working relationship. One of Keith Duckworth's first jobs at Cosworth was helping make the Ford-Lotus twin-cam four-cylinder reliable for the new Lotus Elan sports car and the Ford-Lotus Cortina sedan. Duckworth's work on both the twin-cam and racing versions of Ford's overhead-valve 997-cc Kent engine brought Cosworth to the attention of Walter Hayes, Ford UK's PR man and de facto motorsports boss.

This was Ford's "Total Performance" era, when the automaker put significant resources into motorsport, to pump up the image of its road cars. Throughout the Sixties, Ford had presence in endurance racing, rally, NASCAR, IndyCar, touring cars, and beginning in 1967, F1. Cosworth's Ford connection strengthened with its first full engine. The 1.0-liter SCA—Single Camshaft, type A— took advantage of Formula 2 regulations that stipulated a production block must be used. Duckworth naturally chose the Ford Kent block he was so familiar with, and Hayes got his company to pay Cosworth £17,500 for its development. Branded Ford on the valve covers, the SCA soon became the F2 engine of choice, winning championships in 1964 and 1965.

While many Lotus Sevens and junior formula cars were powered by Cosworth engines, in Formula 1, the company used Coventry Climax engines, like most British competitors. In 1963, the FIA announced a rule change that would see the 1.5-liter limit in F1 bumped to 3.0-liters, and two years later, Coventry Climax announced that it wouldn't build a new engine to this formula. This put Lotus in a bind.

Chapman knew Duckworth was the guy to build an engine, despite Cosworth never building a Grand Prix engine before. Lotus couldn't afford the project on its own, so in stepped Walter Hayes, who provided £100,000 of Ford's money to build the engine, in exchange for branding rights. With hindsight, a bargain considering the millions spent on the GT40 program. Around the same time, Duckworth was laying the groundwork for a new F2 engine, as a 1.6-liter formula was to be introduced in 1967. It would be based around the Ford Kent block, but it would sport a new four-valve head, giving it the name FVA, Four-Valve, type A.

First Principles: The Official Biography of Keith Duckworth

amazon.com

The prevailing thinking of Formula 1 engine designers was that to increase power, you must increase cylinder count. There is truth to this. For an engine of a given displacement, the best way of making more power is to increase engine speeds, and a great way of increasing engine speeds is by making all the rotating components—crank, rods, pistons, valves, camshafts, etc.—lighter, reducing inertia. In theory, having more cylinders means each individual component is lighter, allowing for higher revs. Ferrari, Maserati, and Honda all made V-12s for the 3.0-liter formula, while BRM brought out an H-16, essentially two flat-eights stacked on top of each other (Lotus would use this engine as a stop-gap in 1966.) Duckworth thought differently. In his official biography he's quoted as saying "I decided that it was always better to work things out from first principles. One of my most important sayings, as a result, is that ‘it is better to be uninformed than ill-informed.’ After all, if you are uninformed your only option is to sit down and think about a solution. If you think hard enough, it is conceivable that you might get to the right answer.'' (First Principles, incidentally, is the title of the book.)

Yes, a greater cylinder count could lead to more horsepower, but you have to think of the car as a complete package. A V-8 would be smaller, lighter, and simpler. According to this magazine's technical analysis of the engine from July 1967, the smaller package would allow for a larger fuel tank. The DFV—Double Four-Valve—was also designed to be a stressed member of the chassis, doing away with the typical rear subframe for suspension.

"Keith was very straightforward," remembers Richard Langford, who worked at Cosworth in the Seventies and now builds racing engines as Langford Performance Engineering. "[He was] a stickler for having it right and pursuing all avenues in design. He was very good at problem solving."

These days, we're used to modularity in engine design, where inline-three, -four, and -six cylinders can be made up of the same basic components, and where a V-8 can (virtually) be born from two four-cylinders. Duckworth was long unconvinced that a DFV could be made up of two FVA, but he eventually came around. Even still, there are many differences. The block is obviously bespoke, and unlike the cast-iron unit in the FVA, the DFV's was made from aluminum. A bore of 85.7 mm is shared between the two, but the DFV's stroke is slightly shorter at 64.8 mm. This is the classic "oversquare" bore-stroke ratio common in race engines and high-performance road-car engines, allowing for higher revs. The 40-degree angle between the valves on the FVA was shortened to 32 degrees for the DFV to improve combustion and as it made the cylinder head slightly narrower.

The 90-degree angle between cylinder banks is typical of a V-8, and in racing, so too is the DFV's use of a flat-plane crankshaft. Duckworth went flat-plane to simplify the exhaust system—compare the "bundle-of-snakes'' headers on a GT40 V-8 to the simple setup on the DFV—and because a flat-plane crankshaft is lighter than the sort of cross-plane crank used in most road-going V-8s. Overall, the engine in its original form was 21.4 inches long, 27 inches wide, and 370 pounds in total. The valvetrain was safe up to 11,500 rpm, but redline was set at 9000 rpm, at which the DFV made its 400-hp power peak. Torque was 270 lb-ft at 7000 rpm, as we noted in our January 1967 issue. (For reference, Ferrari's V-12 of 1967 made 390 hp at 10,000 rpm.)

"The layout, the V-angle approach, having the cold air on the inside of the engine and the hot exhaust gasses coming out the side lead to better packaging," says Matthew Grant, founder of Cosworth-parts-supplier Modatek and a former engineer at Cosworth. "You could put pumps down the side…and if you look even up to today, the layout on a modern F1 engine is almost the same."

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos