Motorsport's Love Of Sparkling Wine Has Been Evolving For Decades

The story of sparkling wine in motorsport tends to start in the same place: with that first accidental champagne spray by Jo Siffert on the podium for the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and then Dan Gurney following suit intentionally the year after. That, though, is only part of a story that had spanned decades prior to that first bubbly shower — and it’s a story that has evolved ever since.

But that story started far earlier.

Read more

10 Sci-Fi Movies to Stream on Netflix Instead of Hatewatching Rebel Moon

Three Decades Later, Someone Has Finally Beaten Tetris On NES

ESPN's First Take continues to be a bizarre cesspool of inappropriate behavior

Ubisoft Swiftly Corrects Star Wars Outlaws ‘Late 2024’ Release Window

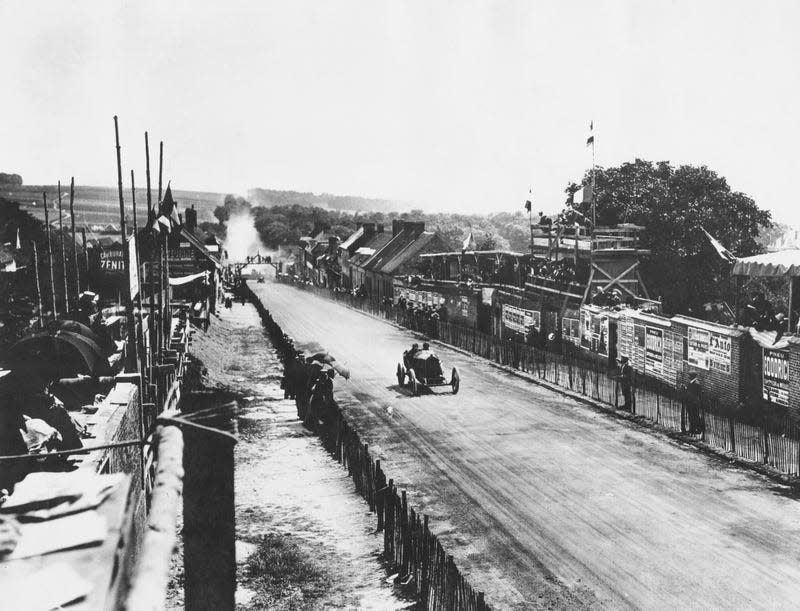

Jules Goux during the 1913 French Grand Prix. I’d need a drink if I was driving one of those cars, too.

After he slashed a tire on the 25th lap of what was then a grueling multi-hour endurance race, Goux allegedly leaped from the car and exclaimed, “Donne moi une bouteille de vin, ou je suis fini” — fetch me a pint of wine, or I’m done.

One of Goux’s crew members — who unsurprisingly, had no wine on hand — dashed into the crowd to commandeer a few bottles from a group of wealthy Pittsburgh spectators. Goux immediately broke open the bottle on the pit wall and took a healthy sip before he jumped back in the car. At every pit stop after, he and his riding mechanic imbibed. Historians debate just how much Goux and his mechanic actually drank that day (the numbers range anywhere from just a few sips to six entire pints), but the story has since gone down in history as one of the first big engagements between champagne and motorsport. (Drinking while racing was later banned during the Indy 500.)

Jack Brabham swigs on a bottle of champagne after the 1959 Monaco Grand Prix

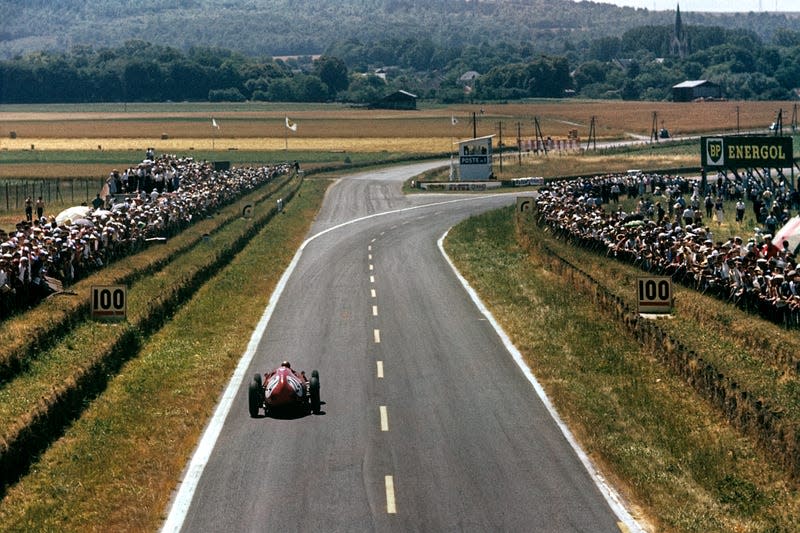

On the continental side, champagne began to play an even bigger role. In 1932, the French Grand Prix was first hosted at Reims-Gueux, though the track was known for hosting other non-championship events beginning in 1925. The track was made up of rural public roads in France’s Champagne region, and as you can imagine, sparkling wine quickly became a critical part of the event — although not while driving.

In author Robert Daley’s book Cars at Speed, the French Grand Prix comes across as one of the most desirable events on the calendar thanks to its generous prizes. The purse for that one event was generally larger than the prizes at any other race, but the region’s local beverage also played a significant role.

“All week before the race the drivers shoot for cases of champagne which are put up by the organizers as prizes for fastest practice laps, and first lap of the day over a specified speed,” Daley wrote. “Usually there are three or more such prizes of 100 bottles each.”

The sweeping Reims-Gueux circuit was one of the fastest and most dangerous on the calendar, with asphalt snaking between vineyards

According to Daley, this made the event particularly exciting. Drivers actually showed up early to dutifully log as many practice laps as possible in hopes of coming away with that day’s champagne prize. Meanwhile, snack vendors sold champagne in droves to spectators, and even journalists were offered the beverage while they worked. Daley wryly notes, “The fact that relatively few sober words have been written about Grands Prix at Reims, accounts in part for the race’s continuing tradition.”

Race fans tend to think of Formula 1 in particular as being the home of the champagne celebration, and it was in fact at a Formula 1 race where the first recorded bottles of champagne were dedicated to podium finishers. In 1950, at Reims-Gueux’s first-ever Formula 1 Grand Prix in the sport’s first season, Juan Manuel Fangio was awarded a bottle of Moët & Chandon that had been donated by the winery. Soon, the winemaker began to provide bottles to winners of other races, and it quickly became customary for winners to expect a refreshing bottle when they climbed from their cars.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos