Why Porsche Doesn't Use a Flat-Six in Its Modern Prototypes

Porsche has long been defined by the flat-six. It's powered the 911 for nearly 50 years and has been behind many of its greatest motorsports achievements. Except, Porsche hasn't put one in a sports prototype for almost 25 years. The last was the 911 GT1 of 1998. Its successor, the LMP2000, was canceled before it ever raced.

Originally, that car, codenamed 9R3, was to get a flat-six, but its designer Weit Huidekoper said it wouldn't work. “If looks could kill I would not be around anymore,” Huidekoper recalled in an interview with motorsports-history site Mulsanne's Corner, “when I mentioned the traditional Porsche flat-six engine as the design's major weakness!" Flat-sixes were Porsche, and nobody wanted to hear that the layout was holding them back. "Previously this engine concept had been their strength, now it was old fashioned and their weakness."

What was that weakness? Aerodynamics. In fact, a single innovation knocked out the flat-six, though you wouldn’t know it if you looked at results alone. Porsche seemed to have a winning formula with its tried-and-true turbo flat six formula, but when you dig deeper you’ll find that the company had been stretching it out for decades past its sell-by date. Flat-six Porsche prototypes spent years winning in spite of their engine’s performance, not because of it. To understand this aerodynamic problem, we have to dip into some history.

When Huidekoper talks about the "traditional Porsche flat-six," traditional is the key word. In the Seventies, Porsche began turbocharging the 911's flat-six—already a decade old at that point—to great effect. Turbocharged flat-sixes powered the triple Le Mans-winning 936 prototype and the popular 934 and 935, the latter of which got its own Le Mans win in 1979. This was an effective program and an efficient one, too. The turbo flat-six was a do-it-all engine. Lessons learned preparing it for a failed run at the 1980 Indy 500, for instance, were folded back into Porsche’s Le Mans program and racked up a win there in 1981. Even by that point, however, the writing was on the wall.

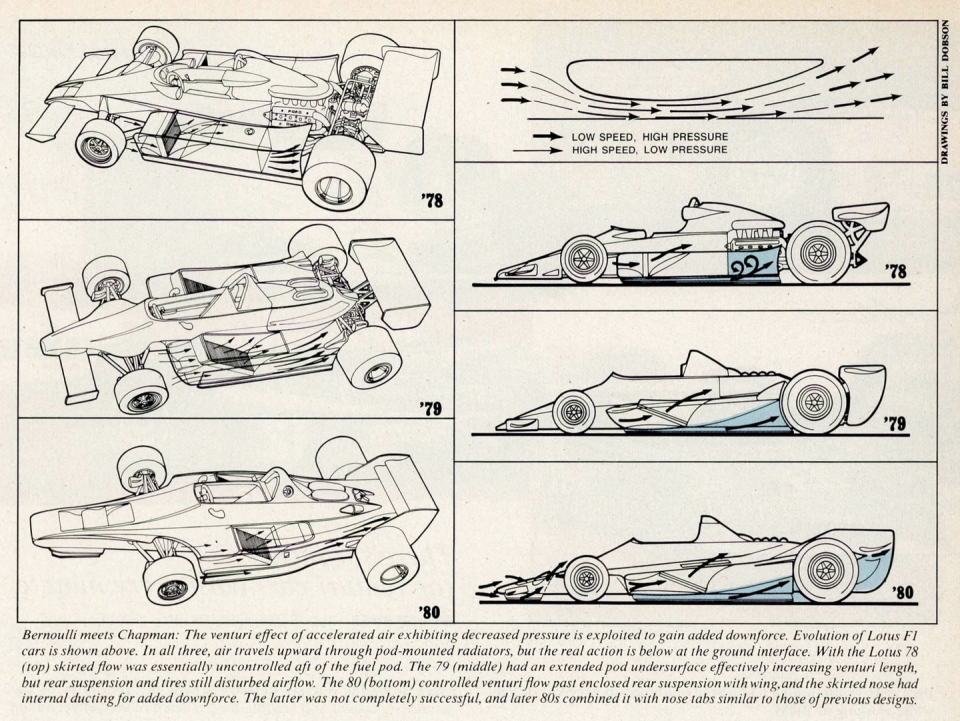

An expiration date emerged in 1977. Lotus debuted the 78, the first Formula 1 car to take advantage of ground effect, wherein the entire car acts like an upside-down airplane wing. This design creates a low-pressure area underneath the car, effectively sucking it to the ground. Ground effect was perfected with the 78's successor, the 79, which won the 1978 world championship with Mario Andretti at the wheel. Competitors had to develop ground-effect cars of their own, or get left well behind.

Ground effect was achieved by venturi tunnels on either side of the car designed to accelerate air, creating the desired low-pressure effect. Lotus, like so many other Formula 1 teams, used Cosworth DFV V-8s, and as this engine was fairly narrow, it made adding venturis on either side quite easy. With a flat engine, the cylinder banks, laid flat on the floor, were right in the way of where you'd put the venturis. Brabham, which used long, wide Alfa Romeo Flat-12s, couldn't add venturis as simply as Lotus. Designer Gordon Murray came up with a sly way of achieving ground effect, an engine-driven fan that sucked air out from under the car. "The fan car, the BT46B, was born out of necessity," Murray once said in a documentary. "Right where you needed the space, we had a flat-12 engine," he said. The fan worked exceedingly well, but was quickly withdrawn over fears it would create a political firestorm.

At the end of the 936's life in 1981, Porsche got to work developing a successor, one that would fit the new Group C regulations for sports prototypes, the 956. Under the leadership of Norbert Singer, the designers looked around at what was state-of-the-art, and naturally, their attention turned to ground effect. Using a flat-six gave Porsche the same issues as Brabham. Things weren't quite so bad, as it didn't have the length of three additional cylinders per side, but the flat-six was arguably one of the 956's biggest weaknesses. Still, regulations dictated that a Group C car was much wider than an F1 car of the day and required a production-based engine. It seemed more sensible to Porsche to evolve its flat-six rather than, say, make a race engine out of the 928's V-8, and history shows it was the right decision.

The width meant that where the Lotus and other ground-effect F1 cars sealed off their underbodies with ground-scraping skirts, the 956, allowed in air from the sides. Regulations stipulated that the floor under the cockpit had to be flat, too, so the 956's venturis began closer towards the rear of the car, running beneath the rear subframe. The company developed two floors for the 956—a higher-downforce short tail, which incorporated a very small diffuser behind the front axle, and the lower-drag long tail, with front diffuser deleted and the side venturis elongated.

What you don't often hear in the story of the 956 and the later 962 was that it wasn't the fastest Group C car. Thanks in large part to its Ferrari twin-turbo V-8, the Lancia LC2 outgunned the 956, regularly taking pole positions in 1983 and 1984. Yet Porsche kept on winning as a result of the far superior reliability of its flat-six. Porsche continued to dominate Group C in 1985-1986, but 1987 saw the World Sportscar Championship go to Jaguar, and the following year, the English automaker ended Porsche's seven-year winning streak at Le Mans. It would be another seven years before Porsche won Le Mans again.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos