2014 Tesla Model S vs 2023 Tesla Model 3 Review: Is Newer Actually Better?

It’s hard to believe that Tesla Inc. turned 20 years old this month, but a lot has changed since the days of downloading high-res Tesla Roadster wallpapers via my parents’ dial-up internet. Founded in 2003, Tesla (formerly Tesla Motors) has evolved from boutique automaker with the Roadster, to an exclusive luxury marque with the Model S and X, to mainstream premium brand with the Model 3 and Y. But building cars is hard, as they say, and it certainly hasn't been an easy road—to say nothing of how much more difficult CEO Elon Musk has made it by being... himself.

Yet Tesla has managed to reach and defend the position of de facto leader of the electric car world. For many shoppers who want decent range, refuse to drive a blob, and hate unreliable charging stations, Tesla is the answer. Legacy automakers are challenging that paradigm with their own EV product blitzes and deals to access the Supercharger network, but Tesla remains the preferred choice for now, still selling about 10 times the number of EVs in America as anyone else in the first half of 2023.

Its cars have suddenly gotten more affordable, too. As of June 2023, a new Model 3 starts at just over $40,000 (approximately $32,700 after the federal EV tax credit). However, the cheapest way into Tesla ownership is to buy a used Model S. The oldest examples can now be found under $20,000, despite selling for almost six figures when new.

I’ve seriously considered buying a used Model S, but I also have reservations about owning a decade-old EV. The recent Model 3 price decreases have changed that calculus, kickstarting the comparison test you’re about to read. Are the savings of a used Model S worth the risk? Do the extra features of a new one justify the cost? And for a company that doesn’t really do “model years,” just how much have its cars changed over time?

Tesla famously doesn’t offer new cars for reviews, so I had to answer these questions on my own. I rented two Teslas with the largest age gap I could find–a 2014 Model S and a 2023 Model 3–and pitted them head-to-head on a 400 mile road trip.

Let the battle begin.

2023 Tesla Model 3 Rear-Wheel Drive

Base price: $40,240 (~$58,860 as optioned)

Powertrain: 192 kW AC permanent magnet synchronous motor | 58 kWh LiFePo battery

Horsepower: 279

Torque: 330 lb-ft

0-60 mph: 5.8 seconds

EPA range: 272 miles, 132 MPGe

Curb weight: 3,885 pounds

Cargo space: 22.9 cubic feet + 3.1 ft³ frunk

Seating capacity: 5

Quick take: It excels at the basics and is still top of the class for EVs, but it lacks personality.

2014 Tesla Model S 60

Base price: $69,000 when new, $18,700-$22,200 used

Powertrain: 225 kW AC induction asynchronous motor | 60 kWh Li-NCA battery

Horsepower: 362 hp

Torque: 325 lb-ft

0-60 mph: 5.9 seconds

EPA range: 208 miles (realistically 175 miles in 2023), 95 MPGe

Curb weight: 4,323 pounds

Cargo space: 26.3 ft³ + 5.3 ft³ frunk

Seating capacity: 5

Quick take: Shrinking range and slower charging betray a car that otherwise far more enjoyable.

The Test

Tesla never intended buyers to cross-shop these two cars, but in the real world, people often did. So much so, that Tesla actually told people to knock it off when anticipation for the new Model 3 caused Model S sales to drop. While this comparison might sound like apples and oranges, both serve as gateways to affordable Tesla ownership. It’s more like… apples to pears. (Does that make the Model X a quince?)

With help from friend and fellow car scribe Alex Hevesy, I plotted a three-day road trip through the Mid-Atlantic, from Baltimore to Valley Forge National Park, to Gettysburg National Park, and back. The giant figure-8 included a mix of highways, country roads, and city traffic, plus it gave us the chance for 120 volt, 240 volt, and D.C. fast charging.

During the trip, I compared subjective features like comfort, convenience and driving feel, as well as objective metrics like energy usage, charging speed, and operating costs. The goal was to find out if the bargain Model S could keep up with its younger brother, or if 10 years of improvements put the Model 3 on top.

It’s difficult to know exact specs without the window stickers, but both Teslas were close to base trim. The Model S featured a 60 kWh battery and single rear motor, netting an EPA estimated range of 208 miles when new. Our test subject lacked popular Tesla options from the time, like air suspension, moonroof, third-row jump seats, and the 85 kWh battery upgrade that boosted range to 265 miles. But it did have real leather seats and Tesla’s Autopilot 1.0 driver assist system, as well as non-original wheels.

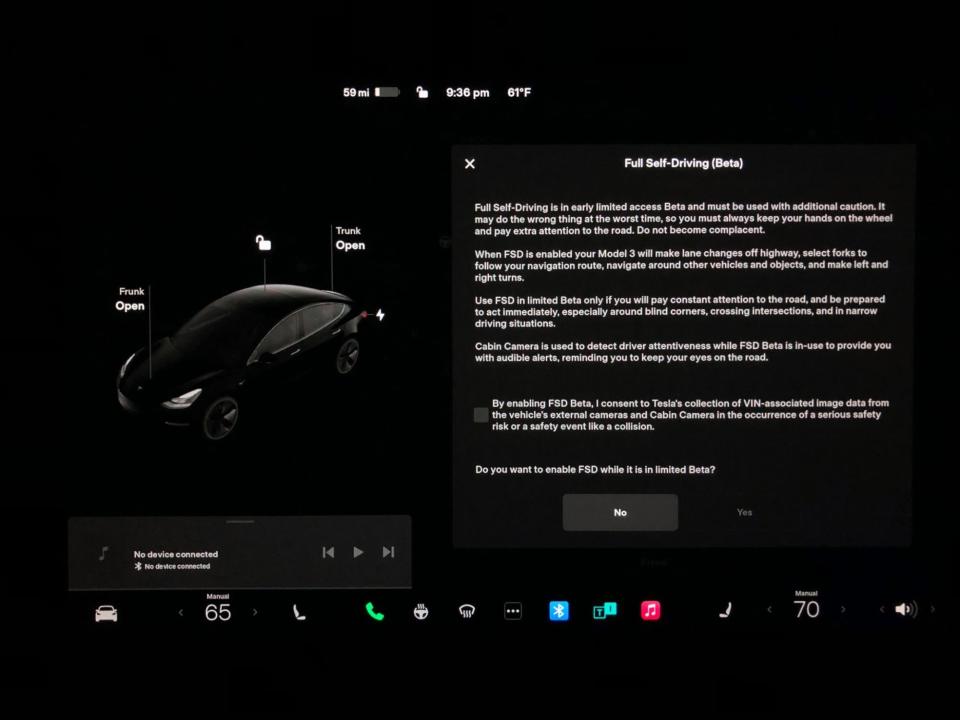

The 2023 Model 3 Rear-Wheel Drive is currently the cheapest new Tesla available, with a 58 kWh battery and a single rear motor that the EPA says will do 272 miles. The only options I noticed were the $1,500 black paint and the controversial $15,000 Full Self-Driving Capability driver-assistance system that legally and demonstrably cannot drive itself. The current Model 3 design is now seven years old, but a major refresh is on the way. In the meantime, engineering teardowns have shown Tesla regularly updates the mechanical bits under the skin—which is where our comparison gets interesting.

Model S vs Model 3 Powertrains

Tesla co-founder Martin Eberhard named the company in honor of Nikola Tesla, inventor of the first practical asynchronous AC induction motor. All Tesla vehicles used this motor design until the 2017 Model 3 debuted with an “internal permanent magnet synchronous reluctance motor” or IPM-SynRM.

For enthusiasts, a common critique of EVs is that because an electric motor is so much simpler than an internal combustion engine, there’s a lot less room for companies to differentiate themselves with engineering. The first part is true, e-motors are simpler. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to push the envelope, and the IPM-SynRM motor is a great example.

Most electric motors work on the same principle: electromagnets create rotating magnetic fields in a stationary cylindrical enclosure, called the stator, that spin a central shaft in the middle, called the rotor. How that rotor is magnetized varies.

In an AC induction motor, a current is wirelessly “induced” into the rotor, which transforms it into a second electromagnet. The induced electromagnetic forces in the rotor cause it to spin as it chases the rotating electromagnetic fields generated by the stator.

In an AC permanent magnet motor, rather than using the current to magnetize the rotor, there are solid magnets built into it, often made with rare earth metals like neodymium and cobalt. When the electromagnets in the stator activate and create a rotating field, those permanent magnets chase those fields and the rotor spins.

In an AC reluctance motor, there are no permanent magnets or live current in the rotor. Instead, it’s made of a ferromagnetic material like iron and shaped so that it wants to spin when it interacts with the stator’s rotating magnetic fields.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=esUb7Zy5Oio\u0026feature=youtu.be

Notice, I’ve described three motor types. That’s because the Model 3’s IPM-SynRM is actually a combination of types 2 and 3. As the excellent animation above explains, permanent magnet motors provide great starting torque but have issues at higher RPM. Reluctance motors are great at high speed but weak at startup. The Model 3’s motor is a brilliant combination that favors permanent magnets at startup then shifts load to the ferromagnetic rotor at higher speeds. Its advanced design is absolutely a testament to the engineering advantage Tesla has gained.

The IPM-SynRM could not exist without modern computer controls, but the basics of the AC induction motor are an elegant, century-old design. Induction motors are cheap to build and do not require permanent magnets made from expensive rare-earth metals, which often come from conflict-prone areas. However, AC induction motors also use more energy than permanent magnet designs.

Conversely, the IPM-SynR motor is smaller and more efficient, but its complex engineering and rare earth magnets make it more expensive, not to mention raise uncomfortable questions about ethically-sourced materials. (Tesla is trying to resolve this.)

Since the Model 3’s debut in 2017, the IPM-SynRM has made its way into all Tesla vehicles, although the dual-motor AWD models actually use both variants, switching between motors for maximum efficiency. As a distant relative of Nikola Tesla (yes, really), I’ve already pointed out the irony of using motors that weren't designed by the man the company is named after, but in context the change makes sense.

With its smaller size and more efficient powertrain, the Model 3 can do more with a lower-capacity battery. The savings of a smaller battery outweigh the increased cost of the motor. Plus, despite the rare-earth magnets in the motor, the smaller battery reduces the car’s total environmental impact.

The efficiency increases also led Tesla in 2021 to switch cell chemistries for standard range Model 3s and Ys from lithium nickel cobalt aluminum (Li-Ion NCA) to less energy-dense but more affordable lithium iron phosphate batteries (LiFePo).

LiFePo batteries don’t require conflict-prone cobalt, and are more durable than Li-Ion NCA batteries when charged to 100% (something Tesla advises against with Li-Ion NCA batteries). Unfortunately, along with being less energy-dense, they do suffer performance loss in cold weather.

At the time of our comparison, Tesla sourced LiFePo cells from Chinese battery giant CATL, which is why the base Model 3 used to qualify for only $3,500 of the full $7,500 U.S. federal EV tax credit, which requires domestic sourcing of battery components. However, as of June 3rd, all new Model 3s qualify for the full credit, meaning Tesla must have switched suppliers, though the company hasn’t confirmed this. Meanwhile, the 2014 Model S has Li-Ion NCA cells from Tesla’s partnership with Panasonic.

The Driving Experience

In light of the incredible powertrain advances Tesla has made in the last decade, I’m disappointed to say that they’re almost imperceptible from the driver’s seat. Both cars produced the standard EV driving experience: they were quick, quiet, and heavy. Driven back to back, contrasts emerged, but most were due to the chassis, not the powertrains.

The Model 3’s combination of lower weight and stiff suspension didn’t mix well with the Pennsylvania roads marred by milk trucks and Amish buggies. The ride was jarring on rough pavement, but the harshness disappeared when the asphalt smoothed out. Despite its heft, the car felt compact and nimble. It could easily dart through a busy intersection to make a left turn before the yellow light turned on me.

Although the Model S weighed 500 pounds more, it wore it better. From the driver’s seat it reminded me of a Chrysler 300; it feels big because it is big, which helps hide the extra mass of the battery. Its wheelbase was only three inches longer than the Model 3’s, but the S handled rough roads more like a luxury car than a sports sedan, with less crashing and bouncing. It was fun to throw this big boy through the curves, although the Model 3 felt much more eager and willing to be driven hard.

The cars were neck and neck for 0-60 mph acceleration. Tesla estimates the 2023 Model 3 Rear Wheel Drive at 5.8 seconds and the 2014 Model S 60 at 5.9 seconds. Both sound unimpressive amidst today’s growing crowd of sub-4 second EVs, and I’ll admit being a little disappointed. Flooring it from a standstill yields a moderate lurch, but it’s not the neck-snapping, face-melting, ludicrous speed available from other Teslas. I found myself wanting more and had to double check that the acceleration settings weren’t left on “chill.”

Regardless, both really shined in the 45-75 mph range, when shooting the gap during a highway pass. Stab the pedal at 55 and there’s no hesitation, no downshifting, no drive-by-wire throttle nonsense; you’re in and out before the GMC Envoy driver doing 10 under has a chance to look up from their iPhone.

I didn’t drive either car hard enough to seriously work the brakes, but both were adequate for everyday driving. The blending of regenerative with friction braking was seamless. Both cars did allow some customization of regen, acceleration, and other settings, but the Model 3 offered more choices, including steering feel. Personally, the “comfort” option was the only one worth tolerating, as even “standard” steering feels like turning through cold molasses. It’s just artificially heavy with no purpose.

A major draw of new Teslas is the availability of advanced driver assist features not available on older cars. The base Model 3 includes Autopilot, which has Traffic-Aware Cruise Control and Autosteer (lane-keeping assist). It can be upgraded to Enhanced Autopilot ($6,000), which includes Navigate on Autopilot (onramp to offramp with traffic-aware cruise control), Auto Lane Change, Autopark, and Smart Summon. Our test Model 3 had Full Self-Driving with a more powerful computer, Traffic Light and Stop Sign Control, and the vague promise of future software updates that will one day, maybe, possibly, enable the car to actually drive itself on surface streets.

Our 2014 Model S had Autopilot 1.0, which only included basic lane keeping, adaptive cruise control, and turn signal-triggered lane changes. Having test driven five different Teslas with various stages of Autopilot, I am familiar with it and by no means am a luddite when it comes to driver assist systems. In general, I like driver aids that keep me from doing something stupid: lane-keeping, auto-braking, etc. I dislike systems that constantly fight me for control. Time and again, I found myself wrestling with Model 3’s wheel and inadvertently deactivating Autopilot because I didn’t like where the car was steering me. I’ve used FSD before, and I don’t find it relaxing or comfortable. And I really don’t like when it suddenly whips me into a different lane because the cameras couldn’t accurately read the road.

The Model 3 used a suite of eight exterior cameras, which made it much more aware of its surroundings than the Model S. As displayed on the screen, it detected vehicles, stop signs, traffic lights, road cones, and more on all four sides. In contrast, the Model S’s radar sensors could only “see” directly in front. Cars passing from behind didn’t pop onto the display until they were well ahead of me. The Model S does have a backup camera, although I don’t believe it’s connected to the Autopilot system.

There’s still some debate over whether the Model 3’s all-camera system is the best for driver-assistance, as there were rumors Tesla might add radar back to its cars. For the time being, it continues to insist camera-based systems are better, and has even begun quietly disabling radar on older cars that had both systems. The Model 3 also has an interior camera to supposedly monitor driver attentiveness for safety reasons, but it really creeped me out, especially since Tesla employees have used the cameras to spy on customers in the past.

Personally, I think the Autopilot 1.0 in the Model S and the basic Autopilot in the Model 3 are both great systems that I would use on a daily basis. However, I don’t see the value of Full Self-Driving and have a hard time justifying such a high cost for a feature that might work someday in the future. Until I can punch in an address and take a nap while the car drives me there, I wouldn’t pay $15,000 extra for it. If anything, the lower price and decent functionality of Enhanced Autopilot are some of the most compelling reasons not to get FSD.

Charging a 10-Year-Old Tesla Isn't as Convenient

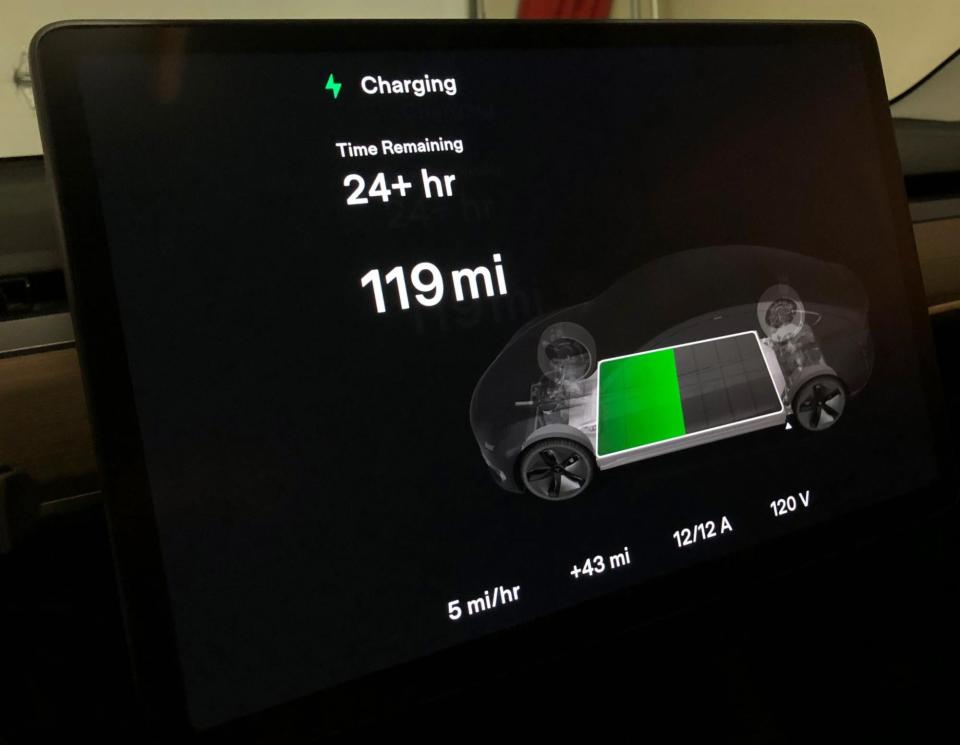

During an overnight stay with a friend, we used the cars’ mobile connectors plus an aftermarket adapter to compare charging speeds. 120 volts is basically a trickle charge, but 240 volt speed varies widely by plug type. Some supply up to 50 amps, but our NEMA 6-20 outlet only offered a measly 20.

For safety reasons, EVs should limit electrical draw to 80% of the circuit’s total amperage when charging, which can either be set manually by the owner or automatically by the car, depending on the connector used.

Tesla measures charging speed in miles (of range added) per hour, so we compared its official estimates with our real world data.

Charge Speeds | Model S | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|

Both cars pulled the same amount of electricity (which isn’t the case when fast charging—more on that later), but the Model 3 added more miles than the Model S because it uses that energy more efficiently. Either way, I’d recommend a higher amp connection for daily use; our 20 amp outlet just wasn’t enough to get a full charge in 8 hours. NEMA 14-50 seems to be the plug of choice, although the LiFePo-powered Model 3 can’t take full advantage of its 50 amp supply, as it’s limited to 32 amps.

Interestingly, early Model S’s offered built-in dual chargers (it still used a single plug, but had double the hardware inside the car), allowing them to suck down a whopping 80 amps through a hard-wired 240 volt / 100 amp wall connector. Capable of adding 60 miles of range per hour, the option was discontinued after the 2016 Model S refresh.

Small differences don’t matter with overnight charging, but speed is everything at a DC fast charging station. When we rolled into a 250 kW Tesla Supercharger at a Sheetz gas station outside of Gettysburg, both batteries were low and ready to go, thanks to automatic battery preconditioning from the cars’ GPS. I watched in amazement as the Model 3 obliterated its older brother.

250 kW Supercharging Session | Model S | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos