Aaron Robinson: The Best Museums Never Stop Reinventing Themselves

From the March 2014 Issue of Car and Driver

Generally, I hate museums. The conceit of cramming some facet of human or natural wonder into a building to be gawped at by shuffling herds, who won’t absorb much about the subject beyond whatever cursory blurb is written in dull mini-print (which they will scrupulously avoid reading so as to arrive more expeditiously at the gift shop and pretzel stand), is anathema to wonder itself. The world is not inert; it lives and moves and waits to be discovered. But museums stop it and stuff it for permanently embalmed display. They sprout from the concrete like weeds in any city claiming civic pride and enough rich donors to get the dirt moved. Art museums, science museums, car museums, and kids museums; museums for the police and fire departments; museums for every ethnic group and religion and industry; museums for every animal, mineral, and vegetable. It’s as if the purpose of our existence is to reduce the world down to heavily curated and filtered dioramas, leaving nothing of the dusty, smelly, non-air-conditioned real thing except acre after sterile acre of tract homes with cable and high-speed internet. At worst, I find museums as depressing as the zoo. A Ferrari doesn’t belong on a pedestal any more than a cheetah belongs in a cage. At best, museums are boring after a few hours. A Ming vase can stop your breath. Six rooms of Ming stop brain function.

Of course, museums are necessary. We can’t re-fight Gettysburg for every generation that wasn’t around to experience it firsthand, nor can we loan out Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” to everybody who’d like to see it up close. You absolutely should not die without visiting the Imperial War Museum in Duxford, England, and there isn’t a bad Smithsonian in the bunch. If you want to be pummeled by classic Bugattis, out in working-class Oxnard, California, there’s a museum packed with 30 of them.

The genesis of the Mullin Automotive Museum, which opened in 2010, mirrors that of many car museums. One very rich guy’s passion got totally out of hand, and eventually not even a 47,000-square-foot building could contain all the loot. Formerly housing the car collection of the late Los Angeles Times publisher Otis Chandler, it was purchased in 2006 by insurance magnate Peter Mullin, who extravagantly redecorated the place to evoke the Paris Salon de l’Automobile in the old days before the war, when Europe’s elite and effete flocked to its soaring halls to order their bespoke bolides. No apparent costs were spared, and the marbled bathroom alone is worth an Instagram. Mullin’s vast hoard is only open to the public on a few select Saturdays. Other buildings hold a workshop and more cars.

The Mullin is exceptional in its collection of mostly prewar art deco French stunners, which claims 16 examples of fluidic oddness from the aeronautical boutique Avions Voisin. There are a dozen Delahayes, including a 1939 Type 165 cabriolet with fabulous rolling breakers of Figoni et Falaschi bodywork, and five Hispano-Suizas stand ready to serve royalty. The very first of only four Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantics ever built spins regally on a pedestal, and somehow it seems okay. Alone, each of Mullin’s 140 or so cars, including the “Lady of the Lake,” the ghostly remains of a 1925 Bugatti Type 22 roadster rescued from 174 feet of water after 73 years submerged, would be the prized jewel of any lesser collection.

Caring for and displaying this gilded fleet in such exquisite surroundings is an expensive hobby. The museum burns through $1.5 million per year, I was told during my visit, but takes in just $350,000 in gate receipts and gift-shop sales. True, Mullin isn’t even trying to make his ends meet (a regular adult ticket is just $15), but other car museums that do are constantly trying to avoid the treacherous shoals of museum economics.

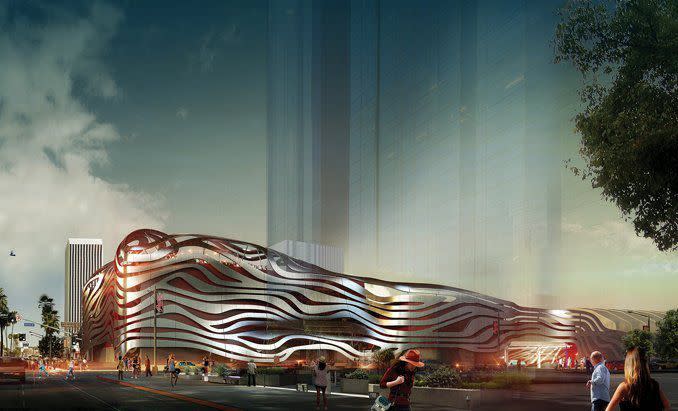

Down in Los Angeles, the Petersen Automotive Museum, established by the granddad of car-magazine publishing, the late Robert E. Petersen, also has to hustle for bucks. It raised a ruckus last summer when a newspaper story revealed that the museum was selling off 119 of its roughly 400 cars as part of an ambitious plan to update the obsolete facility both inside and out. Critics accused the board, which includes Mullin, of hijacking the Petersen’s core mission of telling the story of the auto in Los Angeles by shifting the institution toward displays of esoteric classics that appeal only to society’s higher brows.

To their credit, the Petersen’s helmsmen responded swiftly. They unveiled a plan showing a dramatic metalwork façade applied to the former 1960s department store. Details of the new exhibits indicate a desire to preserve the Petersen’s focus while updating its experience. Though I (generally) hate museums, I can’t wait to see the reborn Petersen, because it’s doing what all museums should do more of: moving and evolving. Just like life.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos