Achievement gap in standardized testing was growing. COVID added fuel to the fire.

Students who score the highest on national tests have been making academic strides over the past decade, while those who score at the bottom are struggling, according to a new brief.

The trend is a particular concern for high-poverty schools, where achievement levels tend to be low and students are still struggling with the compounded traumas of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts said.

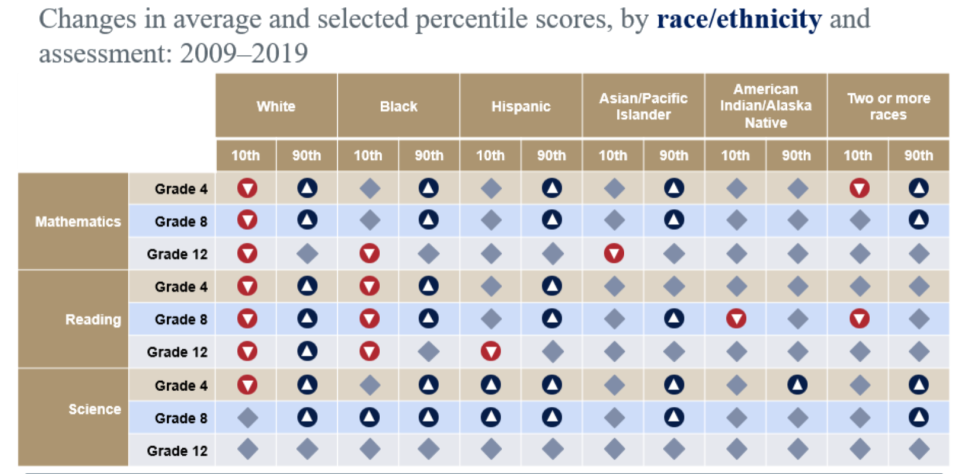

But it's far from the familiar achievement gap narrative: Scores for low-performing white students declined in more assessments compared with their Black and Hispanic peers, for example.

The brief, obtained exclusively by USA TODAY, shows scores for students performing in the bottom percentiles on the National Assessment of Educational Progress fell between 2009 and 2019, while those for students in the top percentiles increased or held steady. The test is administered periodically by the U.S. Department of Education.

More recent data from other standardized tests suggest low and high performers continued to pull apart during the COVID-19 pandemic – especially in reading. Results from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress are set for release in a few weeks.

“This is an alarming, alarming trend and it can't go unnoticed,” said Beverly Perdue, former governor of North Carolina and a member of the National Assessment Governing Board, which published the brief. “It cuts across all spectrums.”

Struggling students need more help

The National Assessment of Educational Progress is the only nationally representative exam for grades four and eight that allows for comparisons across all 50 states and across groups of students over time. It also assesses 12th graders in some states. On average, the brief shows, overall scores didn't change much over the decade starting in 2009.

Yet math and reading scores for fourth, eighth and 12th graders in the bottom 10th percentile significantly decreased in that period. Compared to scores from 2009, more students in 2019 were unable to perform at the "proficient" level, essentially indicating a lack of competence in the subject matter.

What offset their downward spiral was the ever-growing achievement of students on the other end of the spectrum: Among students performing in the 90th percentile, scores increased for most participating grade levels and subjects.

“If you just look at the averages, you don’t detect change,” said Ebony Walton, a statistician for the National Assessment of Educational Progress. “But when you look underneath the hood, you actually do see change. It’s not the magnitude that’s the story here – it’s the direction. We’re seeing these student groups separate.”

The pandemic likely accelerated these differences in achievement.

NWEA, a research and educational services organization that develops and administers a suite of commonly used assessments, found a similar pattern in its reading test data. During the pandemic, high achievers made gains in reading at a rate expected for their group as determined by pre-pandemic trends. Reading test gains for low achievers, on the other hand, fell short of expectations for growth.

“We have consistently seen over the pandemic that the gaps that were already there back in 2019 have only widened … pushing those low achievers further down below national averages,” said Karyn Lewis, the director of the assessment group's Center for School and Student Progress.

Chronic absenteeism: Schools struggled to track who missed class during COVID

Achievement gaps have historically been defined on the basis of race. Rarely have the country's schools been held accountable for addressing other forces that contribute to inequities in educational opportunity and achievement, said Alberto Carvalho, superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District.

“We have growing disparities in America and not all of those disparities are necessarily race- and ethnicity-driven,” said Carvalho, who also sits on the National Assessment Governing Board.

Roughly a third of low performers on the 2019 eighth grade reading test are white, compared with about half of the country's public school students.

Black and Hispanic children are and have long been overrepresented in the bottom percentiles. But it's white students who most reflect low performers' downward trend. Scores for white students performing in the 10th percentile dropped in math and reading for all grade levels measured.

Scores for low-performing Hispanic students, on the other hand, improved or remained the same in every grade level and subject minus 12th grade reading. Scores for high-performing Hispanic students also improved or remained the same in every subject. Similar trends were seen for Asian American and Pacific Islander students.

Black low performers also held steady in their scores on the fourth and eighth grade math tests.

Some other noteworthy statistics among students who performed toward the bottom on the 2019 eighth grade reading test:

About 60% have parents who graduated from college.

Roughly 80% speak English as a primary language at home.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos