We Almost Qualified for the 2024 Indy 500, but Only in the Honda IndyCar Simulator

The IndyCar hopped and shimmied over the bumps as I blasted down the back straight of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at more than 230 mph. The nine-degree banking at Turn 3 arrived quickly, and I faded toward the outside wall before diving down toward the apex. It wasn't much, but my focus wavered ever so slightly and the steering wheel dipped a tad more than intended. My front left tire caught the edge of the curb, immediately slinging me into a spin. I slid up and smashed into the wall, sending me back across the track and into the barrier below.

Despite the ferocity of the crash, I was completely fine. The car was undamaged. It didn't cost my team a dime. That's because, while I was strapped in to the carbon-fiber tub of an IndyCar, I wasn't actually at the famous oval track, and the only walls within touching distance were those of Honda's Indianapolis operations center. I was sitting in the latest iteration of the Driver in the Loop (DIL) simulator, one of a few journalists given the chance to test the machinery that the IndyCar pros use to prepare for the biggest race of the year. My quick stint proved just how challenging the greatest spectacle in racing truly is and left me with a better appreciation for the physical and mental toll that the Indy 500 takes when the banking is real, and so are the crashes.

Honda Racing Corporation (HRC)—formerly known as Honda Performance Development (HPD)—first began using the DIL simulator in 2013, and this latest version has a revised vehicle dynamics physics software that is supposed to more accurately re-create the movement of the car as it plunges into corners and moves under braking and acceleration, especially when it comes to yaw, the movement around a vertical axis in the center of the car. Honda also says there have been large improvements in the models used to mimic the grip and wear of the tires.

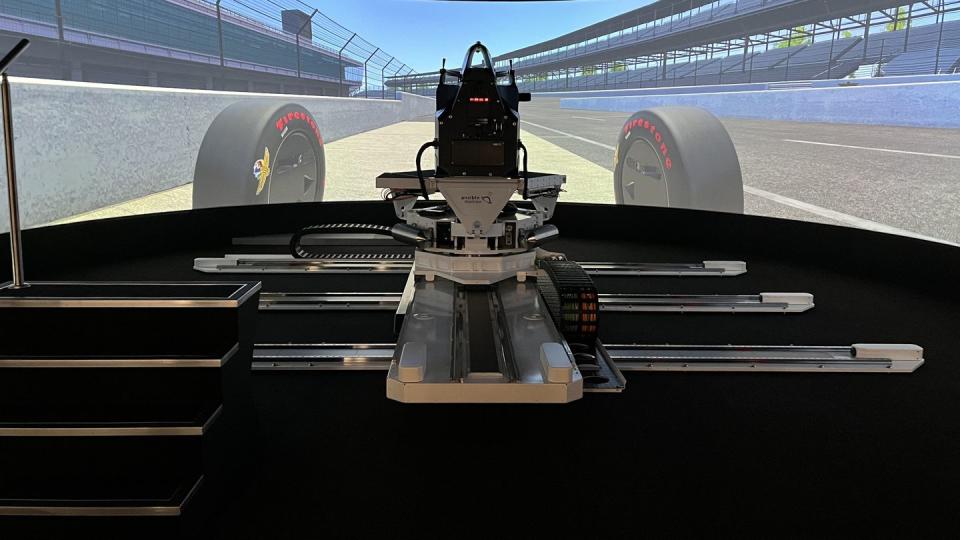

The simulator is an impressive contraption, composed of a carbon tub from a retired IndyCar sitting above the motion platform, which formerly used hydraulics to move the seat around but is now entirely electric. The monocoque is surrounded by a curved wraparound display that measures over eight feet high and fills your field of vision. Honda says the setup generates up to 1.5 megabytes of data each second, with multiple cameras that line up their footage with the data. The simulator can also be set up as the Acura ARX-06 hybrid that races in the GTP class of the IMSA endurance series.

The simulator is a hugely important tool for the teams and drivers, saving time and money while allowing them to test different car setups quicker and without the risk of a real-world test.

But the Saturday before the Indianapolis 500, instead of the simulator being used by a driver for one last tuneup before the big race, Honda was letting this overly confident auto journalist attempt to fulfill his unrealized aspirations to race at the 500.

The biggest misconception about oval racing is that because the cars only turn in one direction—instead of snaking left and right around a road or street course—racing on an oval track is somehow easy. Spoiler alert: it most certainly is not. The difficulty begins with getting into first gear, accomplished via a hand clutch with an incredibly short travel which, admittedly, led to a few stalls. Once you're in motion, you get to experience challenge number two, the steering.

Your daily commute is made exponentially easier because of power steering, which reduces the effort needed to turn the wheel via a hydraulic pump or electric motor. IndyCars lack power steering and the result is exhausting. The steering was heavier than any car I'd ever driven, and it took incredible force to turn the wheel smoothly. Smooth hands are paramount at Indy, since any slight overcorrection can send you into a spin and aggressively sawing at the wheel scrubs speed.

The difficulty turning is compounded by the bumps in the pavement, which reverberated up into the simulator's cockpit and jolted the steering wheel around in my hands. Even worse, I was driving without gloves, my palms quickly becoming sweaty and making it even harder to hold the wheel steady throughout the long turns.

There's also no chance to rest. Even the straightaways require input. When IndyCars race at oval tracks, they run an asymmetrical setup designed specifically for left turns, including aerodynamics, unusual camber angles, weight distribution, and spring and damper weights. This means when you get to the straight the car tugs to the left, trying to shoot you into the inside barrier, so you need to keep the steering wheel angled to the right. After several laps both my forearms and the lower part of my thumbs had begun to burn, and while all I wanted was a brief moment of respite to stretch my hands, the car's constant insistence on turning left meant there was no time for even the briefest of breaks.

It was also tricky adjusting to the transparent speed that everything occurs at around the speedway. After spending a lap feeling out the car and lifting in every corner, I put the pedal to the floor and pinned it flat in all four turns like the pros do in qualifying. Even in the virtual world, going over 230 mph feels absurdly fast. The car eats up straightaways in an instant, with a full lap around the 2.5-mile oval taking as little as 40 seconds. Everything happens faster in the turns too. Steer into the corner and all of a sudden you're nearly on the curb, and as you exit the corner you begin hurtling toward the outside wall. You want to get as close to the wall as possible without touching it but you can't look at the wall, so the entire risk of clipping the wall is calculated via peripheral vision.

Eventually I settled into a rhythm, losing track of time and entering a sort of flow state. I had mostly sorted out how to keep the steering wheel as tranquil as possible, knew where I wanted to turn into each left-hander, and felt comfortable letting the car slide back up the track towards the hard outer perimeter. I later learned that I clocked a lap with an average speed of 232 mph—a four-lap average of 232 mph would have put me in the top 20 in this year's Indy 500 qualifying. Then moments later I faltered, and there was my crash.

After clambering from the cockpit, wringing out my aching hands, I mentioned just how challenging the lack of power steering was. That's when the engineer running the simulator told me they had the steering weight set to 60 percent of the real thing, and I realized as hard as it had been, I still wasn't even close to experiencing the full scope of driving an IndyCar at the 500.

Not only was I not wrestling with the whole might of the steering, but I obviously wasn't also contending with the immense g-forces created by the high speeds and banked turns. Weather also wasn't a concern—while I was certainly sweating, I was sitting in an air-conditioned room instead of dealing with a track temperature of 100-plus degrees. And although the simulator has a weather model that can be minutely adjusted, it was set for me to be a perfect, skyless day, whereas real-life throws ever-changing temperatures and surprise gusts of wind at the drivers. I also didn't have to save fuel or adjust tools like the weight jacker or anti-roll bars, and most importantly, I was alone on track.

The next day, on the final lap of the 2024 Indianapolis 500, Josef Newgarden swept around the outside of Pato O’Ward in turn 3, an audacious move which put his car inches from that of his competitor and off of the preferred line. It was an undoubtedly impressive overtake, a risk that paid off handily when Newgarden took the checked flag to win his second, and second-in-a-row, 500. While I will never cross the line to the cheers of the Indianapolis crowd—let alone finish 33rd—the simulator illuminated just how brave, consistent, and precise IndyCar drivers are, and let me live out my Indy 500 dream without the risk—or, let’s be honest, certainty—of great bodily harm.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos