From the Archives: Road Tripping from Minnesota to Louisiana in a Dodge Viper

Alongside the banks of the Mississippi runs another river, an 1855-mile stretch of road that anchors the heart of Louisiana to the farthest reach of Minnesota. On a brisk day in late June, we jumped into the stream of asphalt in Dodge's rough and ready Viper and let it carry us to places where no one worries about eating healthy or missing an episode of Seinfeld, to the land where the blues was born—somewhere along Highway 61.

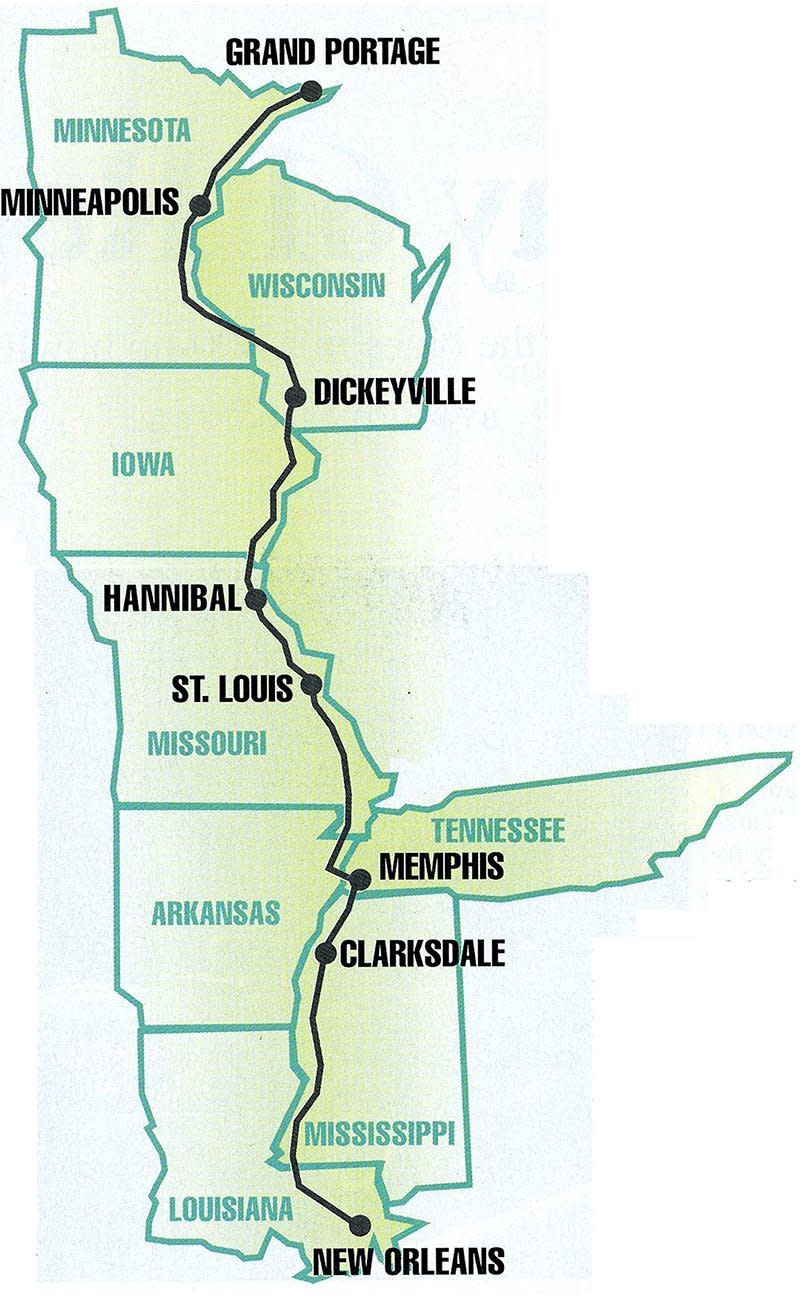

The U.S. government created Highway 61 in 1928 by piecing together a north-south companion to Route 66 from existing patches of road. The resulting highway crossed rocky bluffs, flood plains, and silt-rich farmland on its way south from Grand Portage, Minnesota, to New Orleans.

It was on the rural South that the new road would have the greatest impact. Highway 61 arrived in the Mississippi Delta at about the same time as the mechanical cotton harvester. The harvester's inventors, John and Mack Rust, promised that eight of the machines could pick a 40-acre field clean in a day, a feat that took 50 men and women. They kept their promise, and with the swipe of a machine's arm the Delta sharecropper was made obsolete.

Soon the narrow two-lane road swelled with the ranks of displaced sharecroppers. After 1940, five million Southern blacks were disgorged from the cotton plantations, another spasm in the drawn-out death of American slavery. Lured by the promise of prosperity in the big cities, they headed north out of the Delta, carrying the blues with them, on the road that led to Memphis and beyond.

If 10 days in a black Dodge Viper sounds like nirvana, well ...yes.

But a Cadillac STS it wasn't. Mild-mannered Arizona grad student Biff Rosenberg and I approached 10 days in search of the blues with some reservations—at better hotels, that is, because the Viper had no criminal-deterring door locks (no door handles, either). We took sunscreen but still fried like Cajun catfish in the southern sun.

We ditched the spare tire and jack with the realization that the Dodge dealer in Hannibal, Missouri, probably did not carry a 335/35ZR-17 directional replacement tire anyway. Also, we needed the luggage room. With only two soft-sided bags, a map, and three tape cases, even the footwells were full.

Dylan's "Highway 61 Revisited" in the tape deck, we crossed into Minnesota. There were no blues here, only a sea of blond, fair-skinned Scandinavians, the residue of pioneers who crossed the country looking for a place like home, found it in Minnesota, and stayed. Here, the road never veers more than 20 degrees from its straight-line path, insulated by lanky silver birch trees and the steel-blue cold of Lake Superior, which never reaches more than 60 degrees, even at the height of summer.

The road wrapped itself in a neat bow around Duluth, then trailed out into the emptier reaches of Minnesota like a vine tendril. Outside Duluth, where the sun burned off the lead-colored clouds and the sky opened into a Duke blue, Highway 61 silently merged into the Interstate that brought us into Minneapolis.

In the home of Bob Mould and the Replacements, the blues took a back seat to alternative rock. We cruised Hennepin Avenue, where the students from the University of Minnesota come out to play after hours, and unsuccessfully asked around for the hot clubs of the day. After five hours of top-down trolling, we came up with a three-way tie for the most interesting person we met:

1. Bachelorette Number One: "Okay, guys, here's a quick marketing question for you,” one of a gaggle of female marketing majors asked us. "What do you think of this exciting new product?" Pinned to the chest of the unlucky, soon-to-be-married pre-M.B.A. was a bright bouquet of condoms, sagging like a bunch of wilted flowers.

2. The Weird Chick: Later, we pass an exotic, thin-limbed creature in cat-eye glasses, a leopard-print jumpsuit, and what must have been a velociraptor pelt draped around her shoulders. "You can take off your ties now, guys," she grimaced as she trudged urgently along.

3. Chris. the University of South Dakota medical student: This girl was trouble. She came to Minnesota for a vacation. She hopped into the Viper at a street corner and screamed, "Take me for a ride!" Her friends were relieved when we returned: "Thanks for not chopping her up and dumping her in the river."

Heading out of town each morning, we repeatedly fought the urge to leave smoking trails. We managed to wait until we hit the city limits on this cloudless 75-degree day. Just south of Minneapolis, we found an open stretch of road, a jungle gym for the Viper's 4.4-second zero-to-60 prowess and 0.91 g of stick. Sand-colored bluffs flanked the cresting river, still three weeks away from swamping eastern Iowa but already three feet above flood stage as we headed south into Wisconsin.

Thick bellies of green, dotted with dairy farms and belted in by smooth blacktop, made up the western slice of the state. Holsteins lowed contentedly as we pushed the Viper past the last farmhouses and Lutheran churches at the edge of a quiet town. The road wasn't kinked enough to judge the Viper's handling, but it had plenty of smooth straights where we hung on for quick blasts up to 120 mph, the speed at which the rush of wind past our ears overcame the Viper's flat V-10 rasp.

Our impromptu speed-appreciation session grabbed the attention of a fiftysomething Harley and Gold Wing crew parked at the Dickeyville 76 station and of a Mustang that we politely dusted as we rolled into Iowa. John Mellencamp offered up "Pink Houses" as the sun dipped toward the horizon, scattering dusty gold light across black earth and glinting off barbed-wire fences. Finally it sank behind bales of ale-colored hay rolled into sleeping bags on the family-room shag of Iowa.

The constellation of bugs smeared across the Viper's windshield turned into a constellation of stars as we neared Burlington. The uninterrupted sun left the early evening warm, with a breeze laced with humidity from the nearby flood plain. Stevie Ray Vaughn percolated his brand of electrified blues, dropping notes like the dime-sized splashes of rain that come before a heavy downpour.

The Viper's blatty V-10 drone left our ears in Fort Madison as we downed fresh peach milkshakes. As usual, a crowd collected around the Viper in less than 10 minutes. A 15-year-old local who bore a suspicious resemblance to Pugsley Addams asked if we were from "Great Lakes" like our license plate said (it also said "Michigan'). His chum, with a note of challenge in his voice, said solemnly, "We had something that was almost as fast—a '78 Mercury Zephyr with a 460 engine."

Our response was dead silence. His was deadpan. "Only problem was, we couldn't keep enough tire under it."

A steady rain misted the inside windows the next morning while Biff read USA Today's breathless account of the Julia Roberts—Lyle Lovett wedding on the way south into Missouri.

“It’s the old Billy Joel—Christie Brinkley conundrum,” he sighed quietly before blanking out in total incomprehension.

Missouri rose in spots out of the rising flood, but we were forced to detour off 61 for a few miles where the river had washed away the road, possibly into neighboring Illinois. By way of Kahoka, we made it to Hannibal, boyhood home of Samuel Clemens.

Clemens, who became famous as Mark Twain, is the lifeblood of this burg planted at the river's edge about 70 miles upstream from St. Louis. Tourists come to see Clemens's home, which is surrounded by the white picket fence he immortalized in Tom Sawyer, and across the street is the house where young Sam pulled the pigtails of a childhood friend—the friend that became Becky Thatcher.

We dodged the afternoon heat over pecan pie, hopeful that the sticky air wouldn't dissolve into vicious thunderstorms. We still had to see the old St. Louis Courthouse, which used to be the site of slave auctions and was two years old in 1847 when the first Dred Scott decision was handed down beneath its cast-iron dome. If the rain held us up, our only other options were the National Bowling Hall of Fame or the Dental Health Theatre, complete with a carpeted pink tongue and three-foot-tall fiberglass teeth.

We didn't even make the last showing of "Plaque: Public Enemy Number One." The sky bubbled black as tar as we swung the Viper off the St. Louis ring road and slapped on the top. Ten minutes later, the top avulsed itself in a hail of plastic shrapnel, flying metal ribs, and flapping canvas. Before it could completely break loose—but after we'd been clubbed into submission—we pulled to the roadside and saw our mistake: the passenger-side fastener wasn't latched properly. We broke the top free of its bent fastener, stuffed it into the trunk, and headed for the nearest phone.

Two hours later, a new top was on its way to meet us in Memphis and the storms had held off, so we struck out on the town to Laclede's Landing, a collection of bars down by the riverfront that promised some good St. Louis blues and home-brewed beer.

We forgot that it was Monday. Every club that wasn't shuttered was empty, and after two hours of strolling over the cobblestone lanes we called it quits. Our hotel concierge shook his head. "Mondays are Bad Musician night," he revealed. "All the good musicians are off." Three days had gone, and we hadn't heard one note of blues. A day deeper in the heartland, we hit pay dirt.

A 97-degree, 80-percent humidity day curled the skin from our arms as we rolled into Memphis. What used to be the country warehouse for Delta-grown cotton is now a motley collection of H.O.-scale skyscrapers and wide grassy parks. It's also home to what's left of the blues. Which, we discover, is a lot.

Memphis was usually the first stop for sharecroppers turned away from the Delta plantations. From there, Highway 61 went north to St. Louis, and the trains went to Chicago and Detroit. The flow of people went both ways. Former sharecroppers often returned home through Memphis, going back to the Delta to visit relatives left behind.

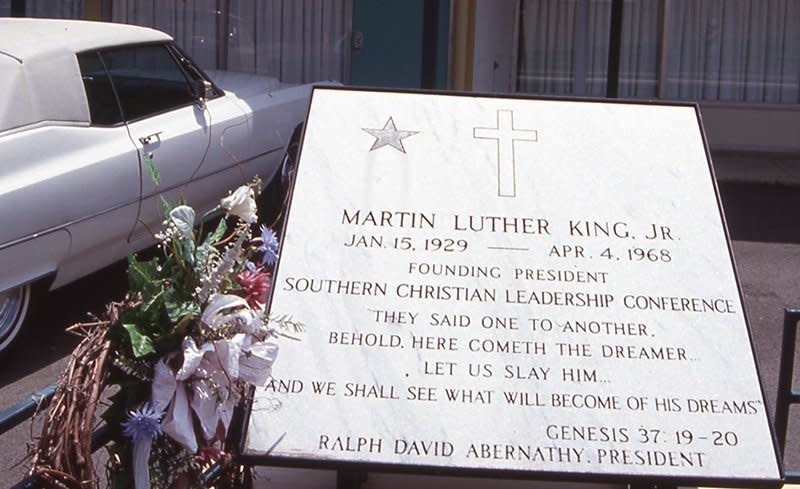

In the same way that Cleveland is the adopted home of rock and roll. Memphis is the foster home of our civil-rights history. Unlike Cleveland, Memphis has a real, tragic claim to the mantle. The National Civil Rights Center is here, a series of virtual-reality exhibits that interact with visitors, placing them on segregated buses, at whites-only lunch counters, and behind the bars of a jail. It's built into the Lorraine Motel where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The exhibits unfold through its halls, ending in room 306 where Dr. King stepped out on a balcony and was shot from a nearby warehouse. A wreath lies at the foot of the balcony, and the motel's parking spaces are filled with vintage CadiIlacs restored to chilling perfection.

Memphians have battled the memory of the assassination and a shaky economy for years. Though it feels more like a big town, the fringes of Memphis suffer big-city crime and blight. But its core is solid. home to some of the greatest music and food to be found anywhere. Real down-home barbecue sits at every turn, waiting for southern-bred arteries that know how to metabolize the rich sauce and marbled meat. The Rendez-Vous got our nod, with a pork tenderloin so thick and juicy we didn't ask if it had the endorsement of the Baptist Memorial ICU.

Even so, most people know Memphis as the home of the seminal music form that eventually spawned rock, country, and jazz. Down on Beale Street, work songs, field hollers, and spirituals were woven together into something new—the blues. When it went north with the sharecroppers, it went electric, and, as the legend goes, gave us rock and roll.

In the early years of rock, Memphis was the place to lay down tracks. Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins cut their first records for the white audiences at Sun Recording Studio at 706 Union Street. Across town, the Stax/Volt studios cranked out hit records for black audiences with hot talent like Rufus and Carla, William Bell, and Otis Redding. You can still visit the Sun studios, even make your own record, but the Stax studios are gone, their "evil influence" stamped out by Bible Belters who had it torn down two years ago.

The lost Stax studios have been supplanted by a whole string of live blues clubs on Beale Street. Jerry Lee Lewis has a club that he says has been open for 16 years (but people whisper that it's only 13). We dropped into B.B. King's place at 143 Beale Street, the “Premiere Blues Address in the World," where the smoky red and cool blue light from the neon sign outside hinted at the action inside.

The King Bs opened with a flash of genteel southern style, with many thanks and welcomes, and promptly launched into raunch. The lead guitarist sang and talked:

I used to make love in a Yugo

It was tight. but it was right.

Then the inimitable Ruby Wilson made her way to the front, dripping in red sequins and lipstick, belting out a Stax/Volt classic, Otis Redding's "(Sittin' on) The Dock of the Bay." The audience swayed in silent admiration for her voice, wide as the nearby river and nearly as deep. Spreading out her ruby-colored gown, Ruby gave acres of feeling to two simple words—"I'm sorry"—for 10 minutes. then switched gears into a driving romp.

The blues had found us.

"You got some pretty legs, honey," she pointed at Biff. "And you got some fine-looking man legs too, baby," she leered at me.

"All right, I need two more booties on the floor," Ruby commanded, ordering a young couple off their chairs and onto the dance floor. At her order, a Bridget Fonda lookalike started shaking her moneymaker, and a dead ringer for Marvin Gaye stepped on the floor and got Ruby's heart fluttering. "You keep on inspiring him, sister girl," she told his date, eying him like Rocky Balboa would a side of USDA Grade A as he gently rocked on in his navy pinstripe suit, red silk tie, pointed-toe shoes, and huge grin.

We watched Memphis disappear in the rearview mirror the next morning, but we carried a little piece of it with us as we twisted the Viper to life. I popped in a collection of Stax/Volt hits, and Booker T. and the M.G.s escorted us out of town in style. Within 10 miles, the last trace of big-city traffic had disappeared. Sixty, 70, then 80—we settled into a decent cruising speed, air rushing over our skin like steamed velvet.

No more troubles with the top, and by then we had grown to appreciate the decent job of packaging the Viper team had done. For what amounts to a transmission tunnel with two people pods, the Viper's cabin is actually quite roomy. The seats are firmer and more supportive than a Corvette's, though with his slight frame Biff could barely reach the pedals. And a 300-mile driving range proved perfect for driver changes every three hours.

Outside Clarksdale, Mississippi, we paused for a minute at the twin pillars of blues history, first where Bessie Smith, the sexually ambivalent goddess of the early blues, died in a car accident on September 17, 1937. Her death was shrouded in controversy. The worst rumors said that Bessie was left to bleed to death while two less injured white men were taken to a local hospital.

A year later, Robert Johnson died suddenly; he was just 27 years old. Legend says that Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49, our next stop, so he could play the blues like his idol Son House. Johnson probably was poisoned by the husband of one of his many paramours, but his and Bessie's stories live on in the elusive history of the blues.

The steady flow of traffic from the Delta northward and from Chicago on south brought the blues its fame. Smith and Johnson were only the first blues artists to gain a national audience. In the coming years, Mississippi would prove as fertile for recording talent as it did for cotton.

The blues was already pregnant with the elements of rock and roll in the Forties and Fifties when it went electric in the bigger, louder clubs in Memphis, St. Louis, and Chicago. One of its fans was a teenage Elvis Presley, who grew up listening to "race records" on the Memphis radio stations. Before long, he played the sounds and words of the blues with his own guitar and with his own beat. As blues historian Alan Lomax puts it, Elvis was basically "a white cracker who brought black music to white America."

At Clarksdale’s Delta Blues Museum, we examined relics and traced the evolution of the blues into rock. As it turns out, Delta-inspired artists filled the rosters of all the major music labels by the 1960s. The first rock-and-roll song, "Rocket 88," was written by Clarksdale native Jackie Brenster. Ike Turner was born in Clarksdale but moved to St. Louis, where he met his wife, Anna Mae Bullock. They made it big when Anna Mae changed her name to Tina and discovered hair extensions and stiletto heels. Sam Cooke hailed from Clarksdale, as did Aretha Franklin's family; Jimmie Rodgers, who popularized steel guitar and probably invented country music, came from Meridian; and of course, Delta bluesman Muddy Waters, whose cypress-wood guitar was made from a piece of his sharecropper's cabin, was born on a plantation in Clarksdale.

The same blues roots that spun off rock and roll had created jazz 30 years earlier. In Vicksburg, the Delta gives way to a greener, cooler road flanked by antebellum mansions that sit off the rod leading into Louisiana, past St. Francisville and into New Orleans, the feverish playground for the first jazz masters, Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton.

Like Memphis, New Orleans made its money on cotton. When it was secured two weeks after the War of 1812 ended, New Orleans became a leading port for indigo and cotton to be exported to Europe. The influx of foreign ships brought more exotic nationalities to mix with the native Creoles and French and spurred the local culture into its own wild, florid language and great food, like the peppery gumbo and crawfish étouffé we found at Old Papa Joe's.

We headed straight for Bourbon Street, our shirts welded to the Viper's leather seats with sweat. We thought it would be the essence of the Big Easy distilled into a smooth shot, but the New Orleans mythology fizzled away somewhere in the procession of the souvenir shops, Hurricane stands, and strip bars. Maybe when Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong blared their own blend of African rhythms and European marching bands, New Orleans had rhythm. Today, it's like Sacramento. Stunned, Buff looked for an explanation. "Even the transvestites looked bored!"

The best ticket was off Bourbon Street, on a side street where a street musician took requests on a worn Epiphone. We asked for the blues, and he launched into a slide version of Robert Johnson's "Travelling Riverside Blues."

"They're selling tradition for tourists," the guitarist complained, animating his thin face and shaking his arms, hidden somewhere in folds of denim. "The city is trying to get rid of us street musicians because it wouldn't be right for the casino. Why are they trying to end something that's been here since the French Quarter was built?" he asked, genuinely puzzled.

Our dollars didn't buy all of his time, so we let him go when a group of college guys stopped. "Hey dude, do you know any Dead?" asked one polo-shirted, khaki'ed jock.

"No but I know some Zeppelin," he smiled at us as he jump-started into Robert Johnson again.

That was our last taste of the blues. After driving 1855 miles, we had wanted to listen to blues and jazz in a New Orleans club on the water and watch the sun dissolve into the Mississippi. But Highway 61 dead-ends in the middle of town outside a McDonald's. Highway 61 had come and gone, once the most important place in the life of the Deep South, now a dead-end road into history. And it was time to give back the Viper.

That, we decided, was the blues.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos