When Autonomous Cars Rule, What Will Happen to Car Culture?

Starting in the mid-’50s, a European radio station broadcast a rock-and-roll show on Saturday and Sunday nights. Radio Luxembourg, as it was called, played the revolutionary new music from America—songs from artists that the stuffy national broadcasters of the U.K. and Europe wouldn’t touch: Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Chuck Berry. A gawky teenager named Keith Richards in the market town of Dartford, east of London, heard Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” for the first time on Radio Luxembourg, and it blew his mind. “Radio Luxembourg was notoriously difficult to keep on station,” Richards writes in his autobiography. “I had a little aerial and walked round the room, holding the radio up to my ear and twisting the aerial. Trying to keep it down because I’d wake Mum and Dad up.” About 250 miles to the north, a 14-year-old named Paul McCartney listened to Radio Luxembourg in bed, through headphones connected by an extension cord to the family radio in the living room. He trained himself to sing just like the voices he heard. A few blocks away, John Lennon would go into a reverie as the Radio Luxembourg broadcast approached, the way a monk would prepare for the catechism. “In the dark front bedroom of his aunt’s house on Menlove Avenue, Lennon invariably sat cross-legged on the end of his bed . . . cradling a full arsenal of notetaking paraphernalia,” Bob Spitz writes in his history of the Beatles. “Skillfully, with caressing fingertips, he massaged the dial of his radio . . . Sometimes he would furiously jot down lyrics to the songs, filling in his own approximation where he’d missed crucial words.”

Rock-and-roll led one of the great cultural revolutions of the 20th century, and that revolution began in teenagers’ bedrooms around the world as obsession. The new music didn’t come to you. You had to find it: You had to rig up your radio, twist the aerial just so, and set aside your Saturday and Sunday nights. You listened over and over again and wrote down the lyrics. If you could find the money, you went out and bought the single—and later the album, which was a cherished object, carefully handled and passed around proudly to your friends. Richards had a notebook as a 15-year-old, where he listed all his favorite songs in longhand. “The first record I bought was Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally,’ ” Richards writes. Half a century later, he still remembered that fact. The new music, for the generation that discovered it, provided an identity. The Beatles were Teddy boys, whose “mongrel [clothing] style was adapted from a fusion of postwar London homosexuals, who wore velvet half collars on Edwardian jackets, with the biker gangs as depicted by Marlon Brando in the film The Wild One,” Spitz explains. “A bootstring tie was added for effect, along with skintight jeans . . . spongy crepe-soled shoes known as ‘brothel creepers,’ muttonchop sideburns, and long hair greased liberally and combed forward to a point that bisected the middle of the forehead.” At the art school where Richards ended up, there was a sharp line between the “beats,” who, he says, were “addicted to the English version of Dixieland jazz,” and those like himself, enamored of rhythm and blues. His use of the word “addicted” is not an accident. These questions mattered: Richards says he crossed the line once, for a knockout named Linda Poitier. But only once.

Do teenagers still feel this way about music? This is not a trivial question. Popular music was one of the first cultural domains to move from analog to digital, and what happened as a result offers an important lesson to all those facing the same transformation. Some of the news is good: Music today is more popular than ever. Teenagers listen to more songs, of greater variety, and have many more opportunities to hear live performances than their counterparts did half a century ago.

But the language of obsession and addiction and identity that marked its analog beginnings has all but disappeared. You don’t have to discover rock-and-roll anymore. There is no cultural equivalent to the Radio Luxembourg broadcast, a thrilling late-night encounter. Streaming services deliver anything you want, whenever you want it. The kid who loves rap dresses much the same way as the kid who loves Kenny Chesney. Will today’s 14-year-old girl remember, 50 years later, the first record she bought? No, because she didn’t buy a record. She didn’t commit to a song. She signed up for a service. For the first waves of teenagers in the rock-and-roll era, the most important question on a first date was: What kind of music do you listen to? That piece of information was deemed to be crucial; it allowed you to locate the stranger in front of you on the adolescent socio-cultural grid. (I started listening to Brian Eno—and have never stopped listening to Brian Eno—purely so I could answer “Brian Eno” to the inevitable first-date question of a very beautiful girl named Marina who listened to Brian Eno.) Teenagers today still ask questions on first dates in order to make socio-cultural determinations. Just not that question. Because how can you answer it if you listen to everything? Popular music has become more ubiquitous and less consequential. It has turned into just another cultural commodity.

“The cultural habits produced of the digital age may have little of the emotional intensity of their predecessors.”

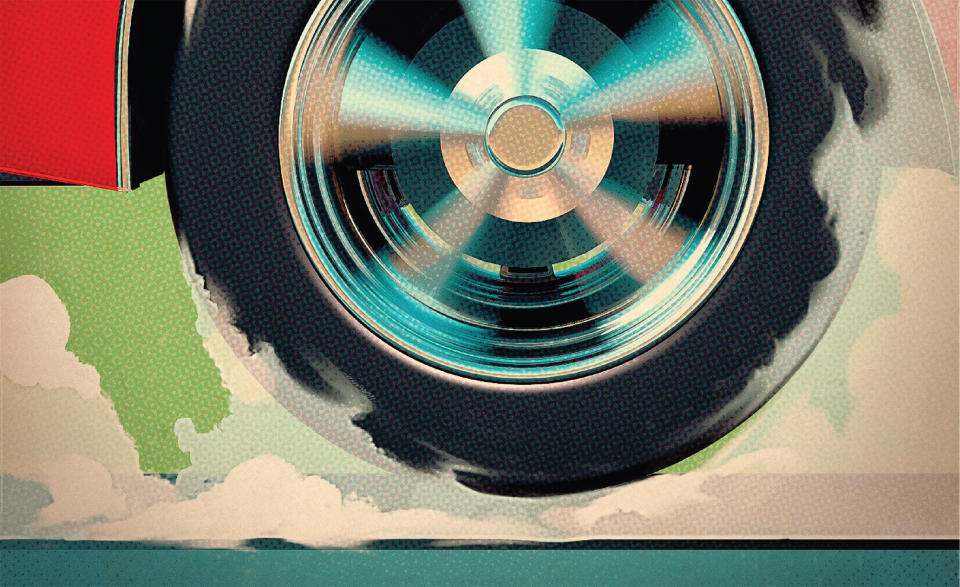

In the previous stories in this section, you’ve read an analysis of what the coming automobile age looks like. How soon will full automation arrive? Can we keep technologically dependent automobiles secure from hackers? How does an accident work, legally, when the driver is merely a passenger? But it is equally important to consider what this new age means. Obsession, addiction, and identity were the building blocks of the analog automobile as well. For a century, the world’s love affair with cars has been sustained by a core of fanatics: tinkerers, gearheads, the automotive parallels of the young Lennon and Richards. Worlds that require effort and interaction build strong bonds of emotional engagement. My father was a college professor in a small town in Ontario in the 1970s and 1980s who insisted on buying high-mileage, second-hand Peugeots, even as one after another, in the face of Canadian winters, rusted down to the frame. Why did he do it? Because to drive a European car, even a lousy one, was a powerful, unstated part of who he was—along with the fact that he read the Bible every morning, took long walks with his dog, and wore a tie when he gardened. (That man produced a son who spends an entirely unhealthy amount of time on Autotrader.) But what does the experience of music teach us? That the cultural habits produced of the digital age may have little of the emotional intensity of their predecessors.

I mean, just take a look at the top 10 musical touring acts of 2016:

1. Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band

2. Beyoncé

3. Coldplay

4. Guns N’ Roses

5. Adele

6. Justin Bieber

7. Paul McCartney

8. Garth Brooks

9. The Rolling Stones

10. Celine Dion

Of them, only three—Beyoncé, Adele, and Justin Bieber—can be said to be truly of the musical moment. Coldplay and Celine Dion are one generation past their musical prime. And the rest of the artists are all, firmly, historical relics. The economic engine of the music business is running on the fumes of middle-aged men, some of whom did their best work during the Nixon administration. Why? Because apparently almost nothing produced in the modern era can match the enduring emotional power of that earlier work. If I were a music executive, that list would terrify me. And by the way, if I were an automobile executive, contemplating a digitized future, I’d be just as frightened.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos