RamSat taking photos while orbiting Earth

The middle school project to build a miniature satellite that is now taking photos from 250 miles above Earth was born around Christmas 2014. That’s when two men who first became friends years ago at Oak Ridge High School had a conversation at their Oak Ridge church.

They were Todd Livesay, a science and technology teacher at Robertsville Middle School (RMS), and Patrick Hull, an aeronautical engineer at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. Hull suggested that the two work together on an educational project.

At first, Livesay resisted the idea and then ran with it after then RMS Principal Bruce Lay asked him to teach an engineering design enrichment class. His students enthusiastically produced miniature satellite frames in 2015 using the classroom’s 3D printer and wrote a computer program to open a payload door.

Then Livesay took them on a field trip to the Marshall Space Flight Center, where they gave a presentation on their work to Hull and others. Additional 3D-printed products and improved presentations to Hull followed.

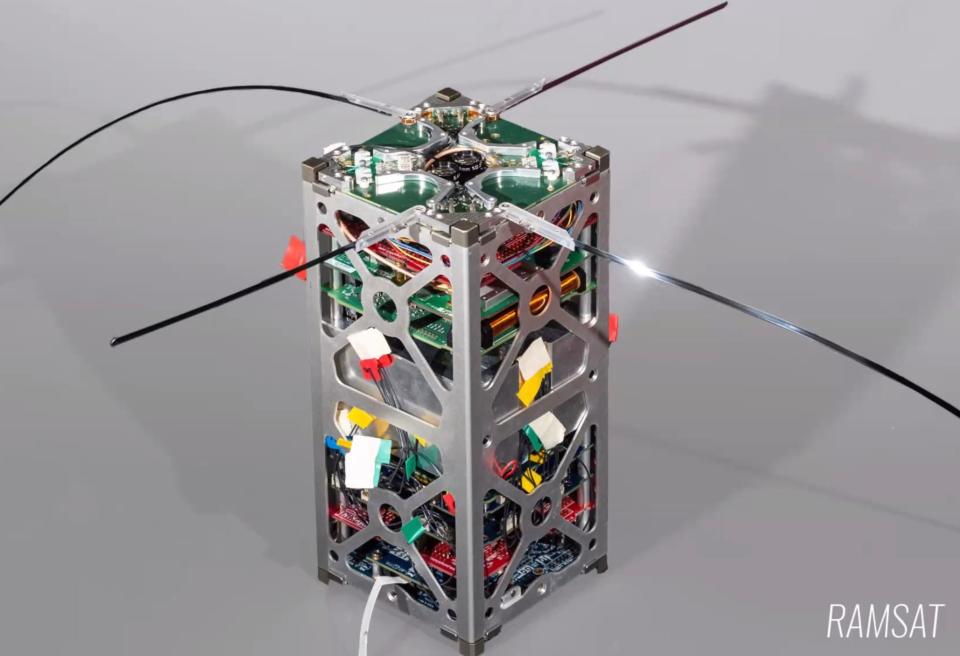

The culmination of the student efforts, guided by mentors, was RamSat, a miniature “CubeSat” satellite named after the RMS mascot and now cruising in outer space. The story of RamSat and a progress report were presented recently by Livesay and three mentors during a public meeting of ORION, the local amateur astronomy organization.

Starting in 2016, mentors for the students were recruited from Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Y-12 National Security Complex. Other recruits included parents and David Andrews, a ham radio operator.

Encouraged by Hull and other NASA employees, Livesay said, several students working with their mentors agreed to write a proposal to NASA to build a CubeSat, which measures under four inches on all sides and weighs less than three pounds. But first, they had to come up with a research mission. After a wildfire devastated forests around Gatlinburg in 2016, two students suggested using the satellite’s cameras to capture images of the damaged forests in the Great Smoky Mountains in a search for signs of regrowth. Hull liked the idea.

“Our proposal was approved and it came in second out of 26 proposals,” Livesay said. “The kids have worked hard on RamSat. They had to tear down the first RamSat when a chip burned out and then rebuild it. The school system has been cooperative concerning purchases of components. But the mentors have truly led this project.”

On June 3, 2021, six-and-a-half years after the Livesay-Hull reunion at Christmas during which 235 RMS students handled RamSat’s many components, the RMS CubeSat was launched by a SpaceX rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla. Some 24 hours later, RamSat reached the International Space Station (ISS).

On June 14, a robotic arm positioned a spring-loaded box outside the ISS. It contained RamSat and another miniature research satellite, called SOAR, built by the University of Manchester in England. After the two CubeSats were deployed in an orbit 250 miles above Earth, they separated.

Almost five months later, RamSat is still traveling about 17,000 miles per hour and making a complete orbit of Earth every 90 minutes. Its two cameras are snapping photographs of cloud-free areas of Earth. RamSat will remain in orbit for six to 12 more months and then burn up in the atmosphere as it falls toward Earth.

The good news is that RamSat and its components, worth $60,000, is working well and taking photos of regions of Earth’s surface. The costs were defrayed by donations from various organizations, including $15,000 from ORNL.

“We didn’t know if anything on this satellite would work,” said Peter Thornton, technical lead for the RamSet project and a mentor of the students, as well as a climate modeling researcher at ORNL. “We did everything we could think of to test and verify that we had our best chance of a functioning system, but so many things can go wrong.”

He reported that all components are functioning as planned, including the antenna, battery, two cameras, flight computer, magnetorquer, radio signal receiver and transmitter, solar panel cells and sun sensors. Livesay noted that the students suggested that RamSat needed a magnetorquer and sun sensors, and they were added.

Inside the RamSat frame is a stack of circuit boards — some homemade and some with commercial off-the-shelf components. An aluminum ballast was added to stabilize temperatures, moderate changes in electrical current and provide mass “so RamSat can stay in orbit as long as possible,” Thornton said.

The RamSat team was excited when they received the first images in August and September. The first image showed part of Lake Superior and a small lake in Minnesota; the second image showed a forested region south of the Great Smoky Mountains and north of Atlanta.

“So far, we have not obtained images over the Gatlinburg fire region,” Thornton said, adding that the satellite passes over the Smokies for five to seven minutes once or twice a day. “The best we have at this point are the images that include Atlanta.

“We weren’t trying to advance the science of space imaging. We were trying to get cameras in space and teach the students about engineering and managing a technical project.

“The primary mission of the project is to provide an impactful and quality educational experience to the students involved. The technical mission objectives of gathering data over Gatlinburg provide important motivation.”

Thornton explained that one camera receives light in the visible spectrum and the other receives light in both the near-infrared and visible spectrum.

“Vegetation is highly reflective in the near-infrared wavelengths and absorptive in the visible wavelengths,” he said. “That way we can highlight the areas that have or don’t have vegetation.”

The digital data in the images taken are relayed as radio signals by RamSat’s antenna to a few of the 400 ground stations in the SatNOGS global network. The RamSat team can send radio commands to the satellite to turn the cameras on or off and to reorient the satellite so the cameras are pointed toward the Earth in daylight. The cameras, as well as the flight computer, are powered by electricity from RamSat’s solar panels, which recharge the battery.

Thornton said that taking photos from RamSat and downlinking and improving them “is a slow and somewhat tedious and painful process. You have to get each of the packets and stitch them back together and make them into a jpeg image. If you miss a packet, the image is scrambled.

“But the short story is that we got interesting images put together after a couple of tries. We corrected them to remove lens glare from the bright sunlight and increased the contrast. That was a good feeling that the cameras are working and that we’re seeing landscapes and bodies of water on planet Earth.”

To see the latest images taken by RamSat and learn more about the little satellite, visit the website developed by Ian Goethert, who also wrote the ground station software. Click on this link: https://sites.google.com/view/ramsat/home.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: RamSat taking photos while orbiting Earth

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos