Motoramic

MotoramicHow the Bugatti Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse can punch all your buttons: Motoramic Drives

As of today, there are four Bugatti Veyron 16.4 Grand Sport Vitesse roadsters in the world, the fastest open-topped cars ever built, each valued at a minimum of $2.4 million and capable of hitting 255 mph. Driving one feels like the ultimate cheat code in the video game of life; maximum power, near invincibility and all the coins. It's also a peek inside the hidden kingdom of Bugatti owners, where $20,000 tire changes seem logical.

First, some genealogy: The Grand Sport Vitesse is the final evolution of the Bugatti Veyron launched in 2005. Those cars had 1,001 horsepower from their 16-cylinder, quad-turbocharged engines; the Grand Sport Vitesse makes an even 1,200 hp, combined with a sleeker body, suspension changes and a removable roof. After building about 350 Veyrons, Bugatti has vowed to build about 100 more.

Parked outside my hotel, the Vitesse sits as if someone pulled to the valet counter in a space shuttle. Awaiting me for my ride was Andy Wallace, a former 24 Hours of LeMans winner who's now Bugatti's on-call driver, showing owners and potential buyers how to get the car to 250 mph and back to zero without dying. It's like being an astronaut whose rocket goes forward instead of up.

Wallace spent several minutes showing me how easy the Vitesse was around suburban Connecticut. He might as well been narrating "50 Shades of Gray" in Esperanto for as much heed as I could muster, because nothing is normal when riding in a vehicle as orange as a Sunkist bottle with more horsepower than any NASCAR, Formula 1 or LeMans car.

A few notes did make it through: The Veyron rides low, requiring some assessment of driveways and curbs. It's a taut ride at everyday speeds, but rarely unpleasant. There are no touch screens, no video displays and perhaps most shockingly, no cupholders — because with 1.4 g's of lateral acceleration, a Starbucks venti would turn into a hot liquid grenade.

Your first surprise is the Vitesse's natural soundtrack. At low speeds, there's just this bass rumble from the 8-liter W-16 engine churning behind your shoulders. But when you blip the throttle, the four turbos spool up to force more air into the engine, then blow off excess pressure through their wastegates in a loud "whooooasssssh." It's as close as I will ever come to having a dragon snort on my neck.

Wallace did one launch of the Vitesse on an on-ramp. I can't say what speed we hit, because I couldn't turn my head to look at the speedometer from the passenger's seat. I can say that Bugatti's claim of 60 mph in 2.5 seconds feels like physical proof that Einstein was right about time slowing if you accelerate fast enough.

With that, Wallace gave me the reins to the dragon.

One of the great untold secrets about the Bugatti Veyron? It's a family car. Not in the sense that it could hold a stroller — it can barely fit a diaper bag in its front hatch — but that it exists only because of ancient familial pride.

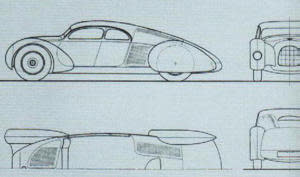

Ettore Bugatti was one of the auto industry's great eccentric geniuses. Between World War I and II, Bugatti not only won more races than any other automaker until Ferrari in the '60s, but built some of the world's finest cars under his name for the royal and the wealthy. He was also given to piques that'd make Steve Jobs blush; when one customer showed up to the French factory in an Opel cab, Bugatti refused to sell him a car. When an electric company sent him a bill in a fashion he thought rude, Bugatti built his own power plant.

While Bugattis cars were triumphing on the track in the early 1930s, a German engineer named Ferdinand Porsche was drafting plans for a new Grand Prix race car, one powered by a massive supercharged V-16 engine. With support from Hitler's German government, Porsche's Auto Union Type C cars and Mercedes' competing entries began to outpace Bugatti, who had no supporter to match.

When Bugatti died in 1947, his firm collapsed. After one failed revival in the early 1990s, Volkswagen chairman Ferdinand Piech had VW buy the rights to the Bugatti name, a move that puzzled other executives. In his first meeting with VW engineers in 1999, Piech set the parameters for what the 21st-century Bugatti should do. It had to produce at least 1,000 hp. It had to reach 62 mph in less than three seconds. It had to surpass a top speed of 252 mph — the fastest speed ever hit at LeMans. And it had to do all of this while being capable of polite trips to the opera.

Ferdinand Porsche had plans to build a luxury road car with his supercharged 16-cylinder world beater that never came true. Seven decades later Piech — Ferdinand Porsche's grandson — finished the job, with Bugatti's coat of arms.

Sitting low in the Veyron's cockpit feels like steering a swank tank, what with the leather from Austrian cows raised — and I'm not making this up — in pastures with no barbed wire and at altitudes where mosquitoes can't reach so that their hides create flawless leather.

The genius of the Veyron isn't just total power but how it delivers it — on call, anytime, repeatedly, without fade in the brakes or skids from the all-wheel-drive. Those Volkswagen engineers took six years to meet Piech's targets, but the Veyron never embarrasses itself at legal speeds. After just a few minutes of practice, you're ready for more speed, and in the Veyron, there's always more speed. Stomping on the pedal will quickly register triple-digit figures — supposedly — or one can use the launch control to recreate aircraft carrier launch scenes from "Top Gun."

But the Veyron engineers don't give you an unlimited length of rope to hang yourself and destroy the car. In everyday driving, the top speed is limited to 200 mph or so, and if you put on the fabric roof in the rain, the top speed drops to a measly 180 mph. Veyron owners who want the full 255 mph must use a special key, inserted on the floor by the driver's seat, that performs 25 system tests to confirm the car is ready for such abuse.

That starts with the tires — a type of Michelin run-flat that's the largest ever built for a road car, and the main reason its speed is capped at 255 mph. The tires will last about 10,000 miles, after which they need a replacement that runs about $20,000. After four tire changes, Michelin requires new wheels, which can run $40,000. Given the typical Bugatti buyer only drives 2,000 miles a year, the tire cost seems less extreme, but even the annual service can run another $20,000 — which requires removing the carbon-fiber body panels to check the Veyron's 10 radiators and 24 gallons of oil, coolants and other liquids.

And those typical Bugatti buyers aren't clipping coupons for Jiffy Lube. There are roughly 90 Bugattis in the United States, most owned by businessmen somewhere along the Bruce Wayne-Lex Luthor axis of wealth. Many own more than one, and their ranks do not yet include a professional athlete, perhaps because even the most successful baller still feels nervous about their future capital needs.

Which brings up the strangest fact of the Bugatti Veyron: At $2.4 million, it may be one of the best values of any new car in the world, because by most reckoning each one costs at least twice that amount to build. It's a strange act of charity that only makes sense when seen as a monument to engineering. Most of us will never acquire the code to owning a Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse, but enjoying one only requires pushing the start button.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos