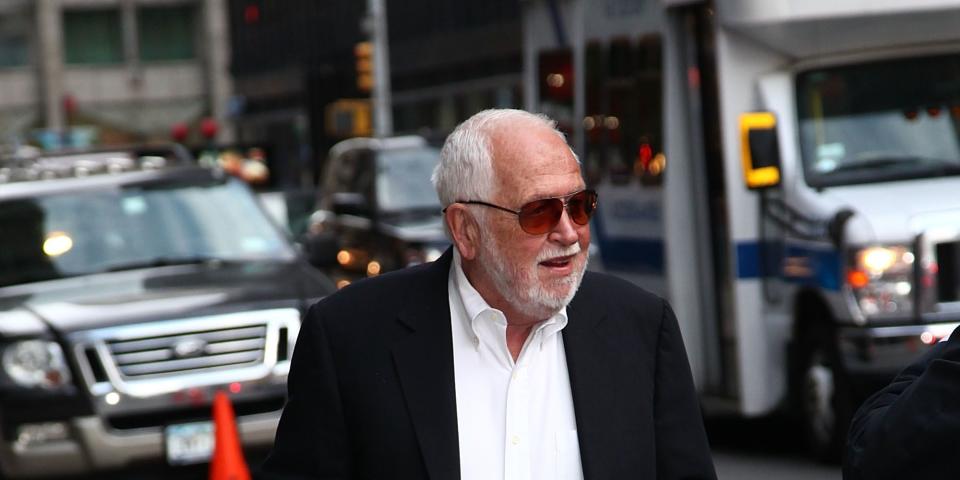

Bruce McCall, Noted Humorist and Former Car and Driver Columnist, Has Died

Bruce McCall, the legendary humorist and longtime contributor to Car and Driver, has died.

McCall was equally prolific as an illustrator as a writer.

His work was particularly adept at skewering the over-the-top style of mid-century American advertising.

Bruce McCall, one of the funniest men to ever write about cars—and also sketch, draw, and paint them with inimitable style—died yesterday at 87, owing to complications arising from Parkinson's Disease.

Though known to the non-enthusiast reading population for the more than 80 covers he created for the New Yorker and the many illustrations and humorous essays he contributed to that toney East Coast periodical, as well as to the madcap 1970s comedic juggernaut, The National Lampoon, McCall distinguished himself to the car-loving world with his often acerbic and always hilarious work for Car and Driver and Automobile Magazine. His illustrations, which showcased the automotive and aeronautical themes that first captured his interest during what he would describe as a resolutely grim Canadian boyhood, defined a genre he'd come to call "retro-futurism," a self-created style that at once mocked and celebrated the over-the-top enthusiasm and huckster's bluster that characterized mid-20th century American marketing, nowhere more shamelessly than in the sale of new automobiles. Overlaid with an Anglo-Canadian's love and loathing of all things British, the genre he helped carve out would become an enduring pillar of American satire, leading even to a short-lived stint in the 1970s as a writer for Saturday Night Live.

A 2020 piece in the New Yorker, "My Life in Cars" detailed McCall’s lifelong fascination with vehicular transport, a topic he'd chronicle still more thoroughly in his addictively readable 2011 first autobiographical volume, "Thin Ice: Coming of Age in Canada." (A second volume, "How Did I Get Here? A Memoir" was released in 2020.) Glorious showcases for McCall's unique blend of melancholy and coruscating wit, the volumes together told the story of how a slight, shy youngster born to dour Scots-Canadian parents (his civil servant father once a PR director for Chrysler of Canada, his mother an alcoholic) spent hours in the bedroom he shared with his brother (one of five siblings), refining an innate artistic ability to the point where he would go on to find gainful employment in Windsor, Ontario, illustrating car brochures. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, cars were not often photographed for ads and brochures but were drawn and painted, and the artists who illustrated them were encouraged to make new model cars look even larger, lower, longer, and wider than they were in real life. This skill would redound to McCall's benefit in later years, with much of his magazine work lampooning the exaggerated style and Space Age promise of the ads that once paid his rent.

As McCall often related, a meeting of minds with the yet-to-become Car and Driver editor (and later Automobile Magazine) founder, David E. Davis, Jr., led to his employment at the venerable Detroit ad agency, Campbell-Ewald, where Davis worked on the Chevrolet account. Davis encouraged the reticent McCall to think bigger. A relocation catapulted the young illustrator from what McCall related as a dreary and largely introverted life into one of color and accomplishment, a success story that would not be complete until Davis encouraged him in the later 1960s to follow him to New York, where Car and Driver was based at the time, and where McCall's magazine career flowered. First, stints writing copy for Ford and Mercedes-Benz at J. Walter Thompson and Ogilvy & Mather raised his standard of living—the Mercedes job would take him for a time to Stuttgart where he was put in charge of the stuffy company's advertising. A chance collaboration for Playboy with C/D's Brock Yates saw him make the most of his boyhood skill for drawing World War II fighting aircraft, along with his fertile imagination and lifelong penchant for absurdist histories, in an illustrated piece called "Major Howdy Bixby’s Album of Forgotten Warbirds," which won the magazine's annual humor award and featured such imaginary planes as the Kakaka "Shirley" Amphibious Pedal-Bomber.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos