Carvana Starts the Slow Climb Back Up to Recovery

From the March/April 2024 issue of Car and Driver.

Ernest "Ernie" Garcia III had a dream. Armed with a degree from Stanford and a $100 million investment courtesy of his father, Ernest Garcia II—the billionaire behind DriveTime, a major used-car dealership chain—Garcia III was uniquely well situated to give his audacious vision a shot. In 2012, he cofounded Carvana, an e-commerce platform for selling used cars. He hoped one day it would become the Amazon of secondhand-car sales, an online operation where you might buy a pre-owned vehicle with no in-store visit, hard sell, or haggling and have the new-to-you car or truck delivered to your home. Though supportive—Carvana began as a subsidiary of DriveTime before being spun off—Garcia the Elder was skeptical, according to his son, and, for years, he was not alone.

"Probably a different company would swing at [this idea] every couple of years until someone eventually cracked the nut. Until that happened, there would just be failures, and people would probably think, 'Oh, see, it doesn't work,' " Garcia III, Carvana's CEO, explains to Car and Driver. "When the reality was, it was just really hard to build something that was good enough to where consumers said, 'That was good, and I'm going to tell my friends.' "

Carvana set out to build that solution.

"What's funny in the story of 2013 through 2016," Garcia says, "was that [investors believed] we had no chance. We started out in Phoenix, and that was the wrong place to be building a startup. And we are a capital-intensive business at a time when the only businesses getting funded were marketplaces. We got to a spot where, basically, private capital dried up for us."

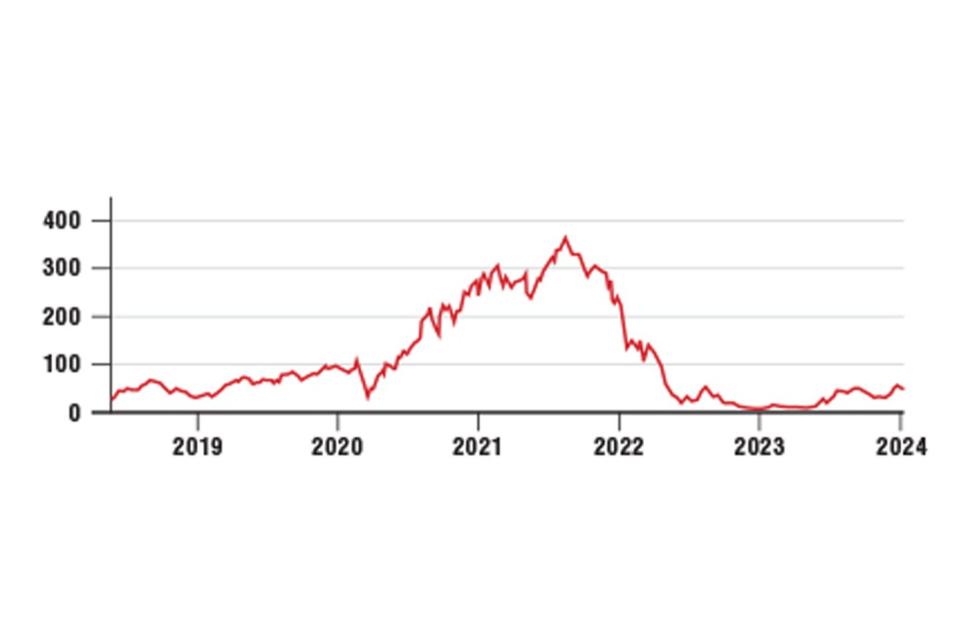

With more money needed for growth, in 2017, Garcia III (the CEO) and Garcia II (the privately held company's biggest shareholder) took the online retailer public. Recalls Garcia the Younger: "We barely made it out. We went public at $15 [a share], and we were trading at $8 over the first week. That was tough. We basically built up from there. By the time we got to 2019, people sort of believed in the business. It made sense. People thought maybe we were onto something."

The company spent significant funds carpet-bombing TV viewers and internet users with ads meant to make Carvana a household name. Then came 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, an intrusion like nothing anyone had experienced. However, as the axiom goes, in the middle of every difficulty lies opportunity. And so it was that a global pandemic, at first supposed to be a ruinous development for the automobile industry, enriched many of its corners mightily. Carvana, the online retailer that could sell, title, and deliver your used car without getting near you, was among them.

The buying and selling of used cars online made newfound sense. The virus drove millions to abandon public transportation, and with stimulus cash floating around and a supply-starved new-car market, the used-car market experienced unprecedented demand.

Also working in Carvana's favor, the constrained new-car supply had the effect of boosting used-car values, which allowed the company to transact sales at higher prices, which enabled it to pay more for people's used cars, which in turn permitted it to grow its inventory faster than its competitors. When things shut down between March and June 2020, Carvana was "almost the only place that could actually purchase or sell a car" without human contact, per independent industry analyst Mel Yu.

Moreover, because Carvana found that people would pay more for cars bought on its platform, it could pay more for trade-ins. "They were only gaining power," Yu says. "Used-car prices and all the revenue they created for Carvana made it look very healthy and very appealing to the financial sector."

Garcia, an agreeable sort with a light, self-deprecating touch who wears the chip of Carvana's roller-coaster reception on his shoulder like a regimental ornament, recalls that the story among investors started to change in mid-2021. "It turned into, 'You're an incredible business on an incredible trajectory,' " he says. "That was kind of wild, the way the narrative can get compressed. All of a sudden, all the trouble we had in the past was forgotten."

You could say that again. Like many modern startups—think Amazon, Lyft, and other tech-dependent ventures—Carvana hadn't recorded a profit in its early years and didn't expect to anytime soon. But its first profitable quarter came in spring 2021. By August, Carvana was trading at over $370 a share. With more than 425,000 sales in 2021, Carvana ranked No. 2 in the Automotive News list of top 100 used-car dealership groups for the year, and at one point, the company was worth $60 billion on paper. Annual gross profit for the year closed in on $2 billion on sales of $12.814 billion, a nearly 143 percent increase over 2020, which itself increased 57 percent from 2019. Sensing that its time had come sooner than expected—it sold its one-millionth car in 2021—the company doubled down on spending to prepare for more growth.

"You get to a place where everyone thinks it's now easy," Garcia says. "Instead of being David, you're Goliath. And people are kind of rooting against you. And you don't even know how that happened. Your head spins, trying to figure out exactly why that happened so quickly."

What happened was that immutable law of physics and finance: the old what goes up must come down. Within a year, Carvana's success story began to unravel. Its spending accelerated in 2021 and 2022 on the optimistic expectation that growth would continue unabated. Instead, the company experienced big losses—including an $806 million loss in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to a letter to shareholders. The bloom was off the rose. Indeed, the rose almost died.

Carvana's share price cratered, briskly tumbling to an all-time low closing price of $3.72 on December 27, 2022. The online business with a big footprint was widely perceived as a virtual house on fire. Carvana had $5.7 billion in debt coming due by 2030, including money borrowed to fund the $2.2 billion purchase of ADESA, the country's second-biggest wholesale automobile auction house. Other nightmares included falling used-car prices (down 15 percent in 2022), higher interest rates, and the capital markets' ever-fickle ways. Ironically, the ADESA purchase addressed many legitimate concerns, with its network of 56 sites where Carvana could inspect, recondition, and house its tsunami of used cars.

Other reputation-denting hiccups came to light. As Carvana scaled up, it appeared to have trouble keeping up with dotting the i's and crossing the t's on the amount of business it was doing. Buying and selling hundreds of thousands of cars around the country created immense amounts of paperwork involving dozens of state motor-vehicle agencies, each with its own rules and protocols but similarly dealing with staffing shortages and offices shuttered because of the pandemic. This led to incidents where Carvana sold cars without supplying proper title and registration in a timely fashion. In January 2023, Carvana settled a dispute with the state of Illinois, admitting that it failed to transfer titles in certain instances, after the state attempted to suspend Carvana's retail dealer's license the previous spring. Also, in 2022, a Carvana location in Michigan faced similar sanctions, and two Carvana locations in Pennsylvania were temporarily prohibited from handling titling and registration matters. In July 2023, however, the Illinois governor signed a bill permitting e-signatures on sales contracts and outlining home-delivery regulation, preserving Carvana's business model while suggesting, implicitly at least, that the state shared some of the blame for the matter of the screwed-up paperwork.

Further negatives emerged. A shareholder derivative suit brought by pension funds alleges that the Garcias sold shares to "select investors handpicked by the Garcias," including themselves, at artificially low market prices. The suit was ongoing at press time. And when shares were higher in September 2021, the Wall Street Journal revealed that Garcia II had offloaded more than $3.6 billion of Carvana stock, according to company filings, representing 16 percent of his holdings.

The elder Garcia's track record didn't inspire market confidence. The son of a onetime liquor-store owner and mayor of Gallup, New Mexico, this up-and-comer had been laid low legally by the savings and loan crisis that started in the late 1980s. In 1990, he pleaded guilty to bank fraud as an associate of Charles Keating, the most high-profile name in the collapse.

Still a young man, Garcia II gravitated toward selling used cars, regrouping to reinvent himself as an energetic subprime financer of pre-owned cars for high-risk customers. He bought Ugly Duckling, a rental-car business, merging it with a new financing arm. In 2002, Garcia and an associate took the company private and renamed it DriveTime. He remains largely behind the scenes with respect to his son's complex online business.

Last summer, many were predicting the worst for Carvana, with its large debt load, but the company has lived to see another day. It took numerous cost-cutting actions, including trimming inventory, reducing workforce, and skipping a Super Bowl ad for 2023, for a total savings claimed to exceed $1 billion. In July, Carvana reached an accommodation with bondholders to restructure its debt and raise further funding. It turns out that the ADESA properties, whose purchase had been pooh-poohed, are among its most valuable assets. And the company's stock price recovered to a more realistic valuation in 2023, surging to over $55 on the announcement of the debt restructuring. Carvana reported a third-quarter profit and adjusted EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) of over $1 billion greater than in 2022.

But continuing the turnaround won't be easy. Ed Kim, president and chief analyst of AutoPacific, notes that Carvana had "gained a reputation for paying top dollar for used cars. Flush with venture-capital money, you can afford to do that, and people loved it. But the drunken partyfest came to an end. They can restructure their debt, but the question is, how big can they be going forward?"

In many ways a tech play that isn't, Carvana marries massive back-office tech with all the old-school logistics and expensive inventory complications of selling used cars on a grand scale, making for a profit-elusive environment. "They ran into some of the same kind of problems that a lot of companies of the last decade, startups like Uber and Lyft, faced," says Reilly Brennan, a partner at Trucks Venture Capital. "As service businesses, they raised a lot of money initially very cheaply through venture capital and very low-interest debt." But Carvana isn't just a service, as its showpiece "vending machines"—expensive to build and with questionable utility or value—should convince you. It is, Brennan proposes, "an almost perfect encapsulation of what a lot of these Silicon Valley startups have done, which is giving you the impression that they've figured out so many amazing parts of the customer experience, except one really important part, which is the making-money piece."

But Steve Greenfield, general partner at the investment firm Automotive Ventures, gives Carvana credit for raising the bar of what's possible. "They had a bold vision of everything that was broken in terms of the consumer experience," he says. "Even if they don't succeed, they have eternally changed the evolution of the online car-shopping and -buying process."

Garcia III contends that his company is here to stay, and he is newly humble. With success, he fears, the company lost its "scrappiness." He concedes mistakes. "For the first time in our life, from mid-2020 to the end of 2021, we were a company that everyone thought positive things about. I don't think that brought out the best in us. I think everyone's better when your back is against the wall."

Adds Garcia: "This business has always made a ton of sense for consumers, and it's always going to be very, very hard. I don't think that story has ever changed, but the way it's characterized has changed so many times... One of our developers who had semi-retired in 2021 asked to come back because, he said, 'We built this thing, and now it's wartime, and I'm not going to miss it.' And I just thought that was very cool."

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos