Dirt Don't Hurt: Behind the Scenes of NASCAR's Return to Dirt-Track Racing

From the October 2013 Issue of Car and Driver

In a singularly sagging season, give NASCAR credit for pluck. Or, at least, for hiring people paid to be plucky. Faced with criticism over perhaps the most deadly dull race in years, the Brickyard 400 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in July, the drivers came out swinging when backed into a corner by the press.

Even surlier than usual, Tony Stewart, who finished fourth, addressed complaints regarding the utter absence of passing. “Look up ‘racing’ in the dictionary and tell me what it says in the dictionary. Then look up ‘passing,’ ” he said. “We’re racing here.” Then he said this: “For some reason in the last 10 years, everybody is on this kick that you have to be passing all the time. It’s racing, not passing. We’re racing.”

Yes, well, look up “boring” in the dictionary, and maybe it should say, “Racing, when nobody passes anybody.”

How dull was the Brickyard 400, or, as it was officially known, the 20th Annual Crown Royal Presents the Samuel Deeds 400 at the Brickyard Powered by BigMachineRecords.com? There were zero passes for the lead, not counting those that occurred because of pit stops or restarts. There were three caution flags, all for stalled cars, and two of those flags were for the same stalled car. And all 43 cars that started, finished, with Ryan Newman winning from the pole. The radio “highlights” summary lasted less than 60 seconds. You would not expect much different if you had 43 rental cars raced by platinum AAA members, except that the NASCAR drivers, admittedly, went faster.

Which brings us to the bizarre, unexpected, blindingly bright spot of the 2013 NASCAR season so far: dirt. On a Wednesday night. In the middle of cornfields in western Ohio.

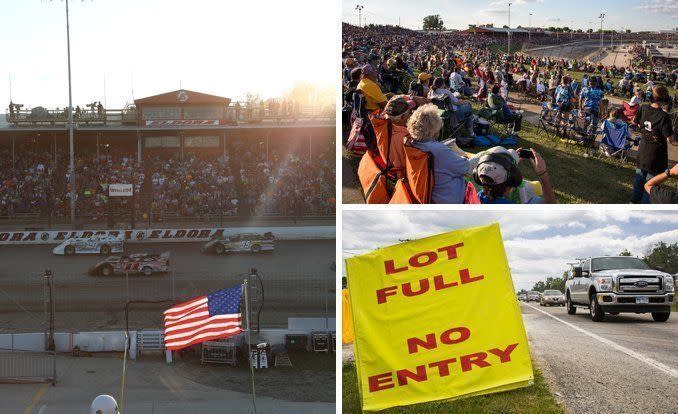

This is brought to us by, of all people, Tony Stewart, who owns Eldora Speedway, a half-mile banked dirt track that opened on June 6, 1954, south of New Weston, Ohio, which has a population of 136. On a Wednesday night in July, just four days before the 20th Annual Crown Royal Presents the yada yada yada, New Weston’s population swelled to more than 23,000.

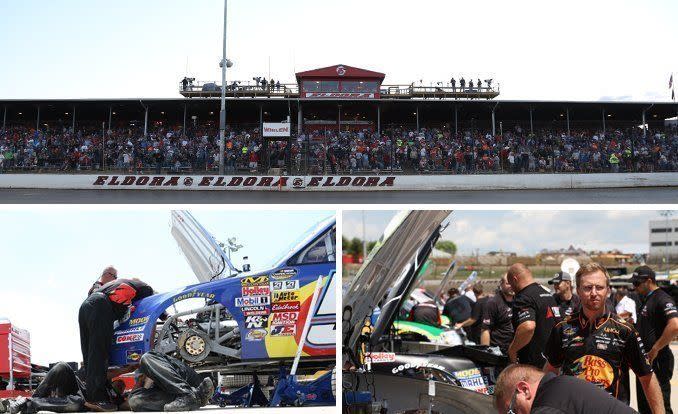

Stewart and Eldora were holding the first major NASCAR dirt-track race since 1970. In this case, it wasn’t cars but trucks, specifically those of the Camping World Truck Series. The track’s 17,782 seats had been sold out since January to fans in 48 states and five foreign countries. More than 5000 additional fans bought standing-room-only tickets. The race was won by Lucky Sperm Club member Austin Dillon, 23, grandson of NASCAR team owner Richard Childress. “This,” Dillon said in victory lane, “is racing.” And yes, there was “passing.” Lots of it.

Eldora Speedway was built by Earl Baltes, a saxophone-playing bandleader who bought the Eldora Ballroom in 1952. Because he had more land than he needed, he built a racetrack. Certifiably in the middle of nowhere, Baltes began promoting the track with the fervor of P.T. Barnum.

The CIA could not have done a better job of disguising a brilliant, savvy promoter as a backwoods hayseed, complete with dungarees, suspenders, a baseball cap with the bill turned up, and Elvis sideburns. Baltes turned Eldora into a magical place—where else could a fan sit at the top of the grandstands, lean over while watching the race, and order a shot from a full bar? Baltes made Eldora into one of those properties that is known worldwide by just one name, like Talladega.

He had racer Pancho Carter preside over the wedding of two gorillas on the front straight. He invented the Eldora 500, with 33 sprint cars running 500 laps. For the annual King’s Royal sprint car race, the winner, wearing a red cape, must kneel down before the white-robed “Royal Sovereign,” who places an enormous, cheesy red-and-gold crown on the racer’s head.

In 2001, Baltes gave away $1 million to the winner of a late-model race, the Eldora Million. Donnie Moran won, the place was packed, and Baltes, at the end of the night, uttered his lifelong catchphrase: “If I could have sold one more hot dog, I would have broke even.”

In 2004, Baltes let it be known that he was planning to sell Eldora. For the track’s ultra-loyal fans, only one buyer was acceptable: Stewart. The three-time NASCAR Sprint Cup champion hails from next-door Indiana, and he started his career racing on dirt. Despite his status in the big show, he still races on dirt 60 nights a year. Stewart bought Eldora and since has successfully walked the tightrope between maintaining tradition—the velvet cape and crown remain for the King’s Royal—and updating the facility. Stewart built luxury suites outside Turn Three and added a large video screen in Turn Two. The track is spotless, for a dirt track.

A couple of years ago, Stewart had a conversation with Steve O’Donnell, NASCAR’s VP of racing operations. “Almost as a joke,” Stewart said, “we started talking about bringing a race to Eldora. A year later, he called and asked if I was serious.” The truck series has been struggling as manufacturer support has dwindled. If a series needed a shot in the arm, it was the trucks.

In its early years, the balance of NASCAR’s schedule was on dirt tracks, but that gradually changed. The last dirt-track race was the Home State 200 at the State Fairgrounds in Raleigh, North Carolina, on September 30, 1970. Twenty-three cars started, 12 finished. Richard Petty won it in a borrowed Plymouth. There were 6000 people in the crowd. Stewart, 42, wasn’t even born yet.

Forty-three years later, Stewart and Eldora were about to host the CarCash Mudsummer Classic. Stewart further upgraded the facilities, adding a helipad with two emergency helicopters standing by. He brought in a state-of-the-art infield care center from North Carolina capable of performing surgery. Local police devised a traffic plan, and additional officers were called in from miles away. Speed TV showed up to televise Tuesday’s practice and Wednesday’s race live, even if it dragged on all night. “We’re prepared to stay until it’s over,” Speed TV spokesman David Harris said.

The truck series normally allows 36 entrants per race, but given the size of Eldora, that was trimmed to 30. The top 20 in points were locked in, and the final 10 spots for the 150-lap main event were determined by the results of five heat races. There were 36 drivers on the preliminary entry list, including some dirt-track ringers such as late-model star Scott Bloomquist and former-sprint-car-ace-turned-NASCAR-driver Dave Blaney in a truck owned by current Sprint Cup champ Brad Keselowski. Stewart’s name wasn’t on the entry list. “I have enough to do,” he said.

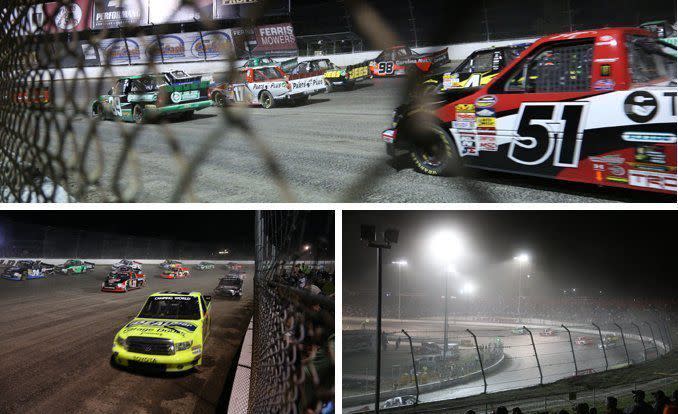

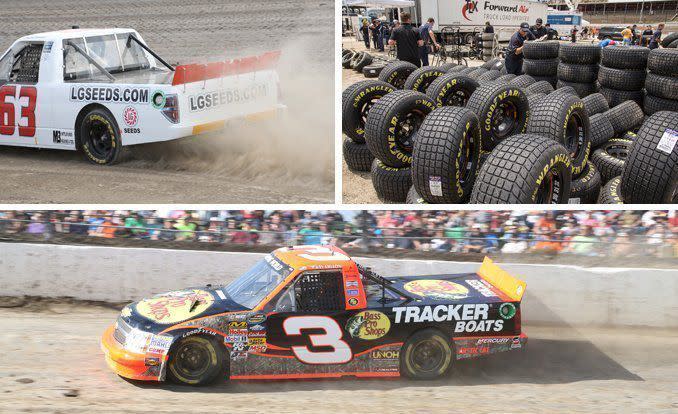

The trucks themselves weren’t purpose-built for dirt. They were taken straight from pavement duty and prepared with modest changes. The front spoiler was removed to prevent it from acting like a snowplow. The shock absorbers were changed, the cooling system was protected from dirt, and Goodyear supplied treaded tires that are similar to those it sells for dirt-modified racing. The windshields were left in, meaning Stewart would have to keep the track relatively dry or flying mud would coat the windshields after a few laps. The drivers had no way to clear the mud.

NASCAR veteran Ken Schrader, who, like Stewart, races on dirt when he can, qualified first and won his heat race. At 58, Schrader also became the oldest NASCAR polesitter in history. Not far behind was Kenny Wallace, another NASCAR racer who runs his dirt modified almost weekly. How were the trucks on dirt? “Heavy,” Schrader said. “By maybe 1000 pounds. And too powerful for the tires, by maybe 400 horsepower.”

It didn’t matter. The race started on time and finished on time. There was only one semi-serious crash despite dire pre-race predictions of carnage based partly on the fact that nearly half the drivers had little or no dirt-track experience.

The last caution flag fell just before the end, resulting in a green-white-checkered finish. It started with Dillon in the lead, followed by future-superstar Kyle Larson, Joey Coulter, and Ryan Newman. Sparks flew, literally, as Newman fought to third place behind Dillon and Coulter. “The guys just raced the daylights out of each other,” Stewart said. Earl Baltes, 92, was there as well, cheering.

To Scott Bloomquist, probably the best dirt late-model driver in history, moving the needle “is the reason we’re here. [If] you have this much beating and banging and passing on asphalt, the cars will end up in the garage, and the drivers might end up in the hospital. This is what [dirt-track drivers] do every night, and it’s cool that a lot of people know that now.”

As for Stewart, the race “wasn’t about money,” though it appears he sold enough hot dogs to break even. “You couldn’t write a check big enough to pay me for how proud I am right now.”

“I think NASCAR made some mistakes,” said Wallace, “and maybe this is about going back and fixing them. We made such a grab for new fans that maybe we forgot about some of the older fans, the people who stopped paying attention when Dale Earnhardt died. This could help bring some of those people back.”

Attendance at the Brickyard 400, which is what it was called before sponsors distended the name, has been on the wane. Multiple sources put the crowd at 70,000, down from about 250,000 in 1994, the race’s first year. There’s no way to know for sure, though, because this year, for the first time in 11 seasons, NASCAR refused to provide attendance estimates.

But declining numbers are no surprise as NASCAR’s season of ennui wears on. Jimmie Johnson is clinically coasting along toward a sixth championship. Headline-maker Danica Patrick’s average finish is 26th this season. Not only are tracks not adding seats, they’re getting rid of them. Daytona International Speedway once had 168,000 places for fans but has been slowly trimming the count to the current 146,000. The track announced in June that it is tearing down the entire backstretch grandstands—another 45,000 seats gone. It’s hard to put a happy face on reducing your seating capacity by more than one-third at your flagship track.

Is Eldora the answer? Probably not. Adding Eldora to the Sprint Cup “Chase for the Championship” or tearing up Daytona to make it dirt are two rather unlikely options. NASCAR on dirt is like discovering a singer who has a great voice only to find out she only knows one song. There are no other dirt tracks in the country that can pull off a novelty show like this. So the Mudsummer Classic will be back next year to prove that people will watch the truck series if you give them a reason, and it might again embarrass the Brickyard 400 for excitement, but it’s unlikely to be more than an isolated grass-roots revelation.

“It’s historic,” Schrader said. “But you’ll have to ask somebody smarter than I am about where we go from here.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos