The Drug Smuggler Porsche That Won Le Mans

Remember the excitement and worry, the sense of danger mixed with ecstasy I felt in the maternity ward when my first child was born. That feels like this. Only instead of nurses, there is a race-car transport driver in cargo shorts. Instead of beeping medical machines, a truck winch groans as the transporter squeezes out of its belly one of the most legendary Porsches of all time.

This story originally appeared in Volume 16 of Road & Track.

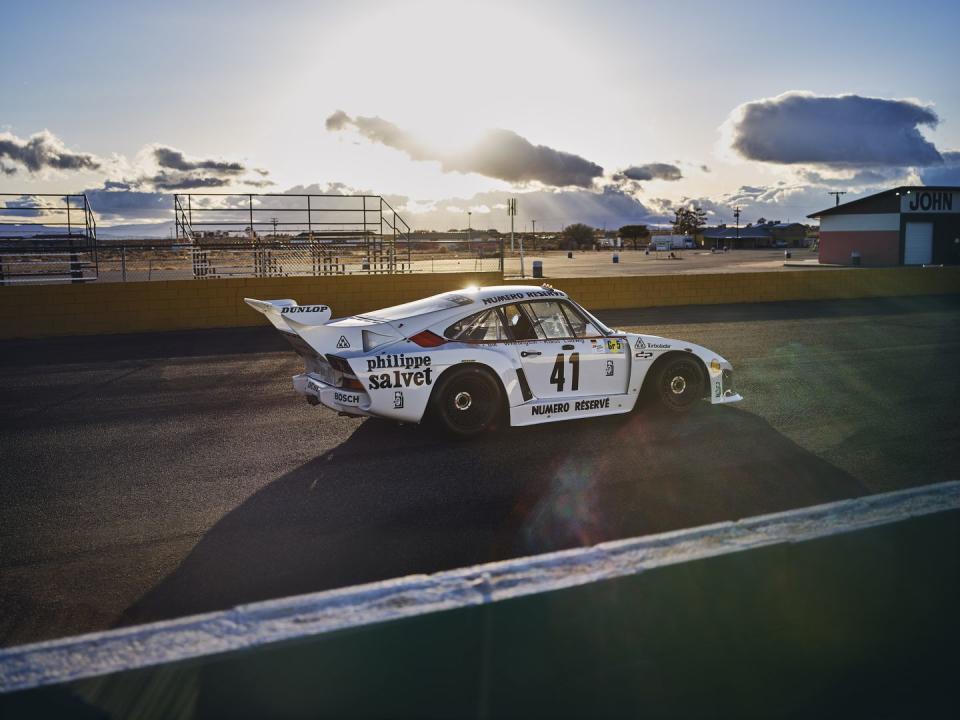

The date: January 7, 2023. The place: Willow Springs International Raceway’s “Big Willow,” the 2.5-mile road course in the Southern California desert with nine corners and elevation changes like a Disney roller coaster. The car: Kremer Racing’s 1979 Le Mans–winning Porsche 935 K3, otherwise known as the Whittington brothers’ Porsche. It began life in Stuttgart as a production 911 RS before the Kremer brothers transformed it into a 935 K3 race car. The vehicle’s story features everything from bags full of drug money to a famous court case, from DEA tricksters to victory at the most important sports-car race on earth.

“Any Porschephile, if they know their stuff, would say this is the most important 911-based car in the world,” says the owner, Bruce Meyer, who was at the track with me. When I ask Ford Motor Company CEO Jim Farley by phone how much he thought it was worth, he says, “I can’t even imagine. That car is priceless.”

Bruce and I were both going to drive. We had the track to ourselves. We stood in pit lane, shivering in the cold and talking. Shouting is more like it, so we could hear each other over the sound of Bruce’s right-hand man, Tom, revving the throttle to get heat into the engine.

When it was my turn, I climbed in, strapped the harness over my shoulders and between my legs, and yanked it all so tight I could hardly breathe.

The interior was all original. Every body panel was original. The car had never been in a crash—not yet, at least. “Be careful,” Meyer says to me. “You don’t want to be ‘that guy.’” Nope. I didn’t.

I gripped the shifter and slipped it into first, the clutch pedal feeling stiff and jumpy as if the car were as nervous as I was. We started to roll on nearly ice-cold pavement. What could possibly go wrong?

To understand why this Porsche is an icon, you must know the story of Bill and Don Whittington. As sons of a racing driver turned businessman, the Whittingtons were raised to be übercompetitive. “Dad had us competing against each other,” Don said in the Seventies. “We had motorcycles almost as soon as we could walk. We’ve raced horses, bikes, boats, airplanes, anything that moves, and always fought each other to win.” They were rich, wild, hard-partying South Florida sportsmen. “They were the Great Gatsby of their era,” recalls Randy Lanier, who won the 1984 IMSA title with the Whittingtons.

In 1979, the Whittingtons went to Le Mans to compete. They were unknown on the international scene then and had paid $100,000 each to get on the Kremer Racing team, a German Porsche outfit that had entered a 935 K3. That was a lot of money in 1979, but to the Whittingtons, money was no object.

The brothers had a secret. They were marijuana smugglers. They owned the Road Atlanta racetrack, and there were stories of airplanes full of stinky weed landing on the back straight under the veil of night.

The day before the race, the Whittingtons approached team owners Manfred and Erwin Kremer and insisted they start and that Kremer Racing’s ace, Klaus Ludwig (who qualified the car), be the third driver. The Kremers were stunned. The conversation unfolded something like this:

“No, no, no,” Manfred Kremer told Don Whittington. “Klaus Ludwig is going to start the race. It is our car.”

Don Whittington said, “Well, what if it’s our car?”

“Then you can do whatever you want.”

“How much would it cost for this to be our car?”

The Kremers huddled with Ludwig and came up with a number—$200,000.

“So Don goes to his trailer,” Meyer explains, “and comes back with $200,000 in cash. It took all day for Manfred’s wife to count the money.”

Some question the veracity of this story. “The fact is, it is true,” Meyer says. “I flew to Germany and interviewed Klaus Ludwig. I interviewed Manfred Kremer in Paris. I knew Bill Whittington well. I interviewed every person involved with this car; every story I heard was identical.”

The most shocking part of the story? While Porsche had entered two prototype 936s with some of the best drivers in the world—Jacky Ickx and Brian Redman, Bob Wollek and Hurley Haywood—the threesome of Bill and Don Whittington and Klaus Ludwig went out and won the race outright in this privately run production-based GT car. The next morning, it was reported all over the world. The New York Times: “Florida Brothers Triumph at Le Mans.

The Whittingtons became legends overnight. And so did their 935.

Out on Big Willow, Turn 1 comes quickly after you exit pit lane. It’s a hard-charging 90-degree left-hander. I swing it with a squeeze on the throttle, so the 850-hp twin-turbo 3.0-liter flat-six lets out a bark. Back in ’79, the car sat on 16-inch wheels and Dunlop tires. Now it’s on 19-inchers all around and a set of Avons. On pavement this cold—with the weight of the engine and transmission hanging out back where it shouldn’t, per the 911 architecture—the slick tires feel like they’re coated in Vaseline. It would be easy to slide into a ditch. I’ve seen it done before on this track, right at the second apex at Turn 2. I’m determined not to do it today.

Big Willow doesn’t have the glamour of Laguna Seca, but it has legit Le Mans tie-ins. The Shelby American team tested Cobras and GT40s here before triumphing at Le Mans in the Sixties, and 20th Century Fox filmed here for Ford v Ferrari. It’s a special place to drive a Le Mans winner.

Turn 3/4—affectionately known as “the Omega”—is an uphill left-right combo that makes you feel like you’re driving up the side of a skyscraper. Camber is tricky. You can see the black stripes all over the pavement leading offtrack where drivers made mistakes. I am sticking at roughly highway speeds. This Porsche doesn’t know how to go slow or motor at low revs. I keep it around 5500 rpm, flipping between second and third. There are no paddle shifters, computer screens, ABS or traction control, or power steering. It’s all mechanical and analog, soulful and full of fury, even at moderate speeds. The chassis is tuned so tightly that I can feel every crack in the road shooting up my spine and into my brainstem. It takes some leg muscle to declutch. The brakes, meanwhile, remain stiff and cold.

Due to the Porsche’s bodywork, the higher the speed, the more downforce the car generates. A German aerodynamicist named Bernie Marcus developed much of this radical bodywork. “There was a lot of freedom, the way the Group 5 regulations were,” Marcus recalls. “One of the rules had to do with the rear window. If you kept the production-car rear window, you could raise the rest of the deck, and that is what we did.” The 935 came from the Porsche factory with a flattened front end. “We took it a step further and came up with a flatter nose, and that made more downforce.”

Turn 8 leads into the fastest section of the track, and I eased onto the throttle. The sensation of driving this car is brute power. It occurred to me as I motored around the final right-hander toward the front straight what kind of skill and nerve it requires to drive this Porsche anywhere near ten-tenths, in close combat, at night, in competition so fierce that losing a tenth of a second consistently on an 8.5-mile lap of la Sarthe could mean the difference between victory and defeat.

But today, there is no checkered flag, no stopwatch. The car is like an old champion pugilist who’s come out to spar because it brings back all those memories. And because, man, it feels good.

Several years after the Whittingtons won Le Mans, they were indicted on cannabis-smuggling and tax-evasion charges. They joked with friends that they were “going to Yale.” In fact, they went to prison. They “lent” their 935 to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum to keep the feds from seizing it. When they got out, they tried to get their car back, but in a highly publicized court case in 2004, they lost. (Bill died in 2021; Don did not respond to interview requests.) The car ended up staying at the Indy museum for 30 years.

About a dozen years ago, Meyer acquired it from the museum in a trade for his 1952 Indy 500–winning “Agajanian Special” (although, he explains, the transaction was slightly more complicated than that). He brought the 935 to Bruce Canepa—the California-based restoration guru whose work with vintage Porsches is unparalleled—to rebuild all the systems, which got it up to its current working order.

In 2014, Meyer brought the 935 to Winter Speed Days at Laguna Seca. By this time, the Whittingtons had gotten out of prison but were back in the news—more trouble with the law. The car was in the paddock when a black Chevrolet SUV unexpectedly rolled up. Three stern-looking men wearing DEA jackets got out and began to circle the 935. Then things got weird. The DEA agents informed Meyer that the Whittington brothers had purchased this car with drug money. So they were going to confiscate the vehicle.

“They had badges,” Meyer says. “They had Glocks.” They also had paperwork signed by a judge. Meyer stood helplessly while the DEA loaded his Porsche, still bearing the names “Bill and Don Whittington,” onto a transporter. People crowded around, with many filming on cellphones. “Bruce was like, ‘Holy crap! My car just got taken from me!’” recalls Farley, who was there. “He had no idea what was going on. He was terrified.”

The DEA guys left the track with the 935. Not until an hour later, when they returned with the car, did Meyer learn that the DEA guys weren’t DEA at all. Meyer had fallen victim to what is now known as “the prank.”

The plot began with Al Arciero of the legendary Arciero IndyCar family, a friend of Meyer’s. He called his buddy Canepa. “I says, ‘Why don’t we have some cops come over? Do a little prank?’” recalls Arciero. The pair got more help from Chip Connor, the vintage racer and Ferrari GTO owner, and Charlie Nearburg, a former land-speed-record holder. They hired a movie producer and actors to play DEA agents. “Canepa got ahold of somebody he knew in Hollywood who knew how to get the actors and props and badges and uniforms,” says Nearburg. “Unofficial documents were prepared that looked very official. These actors pulled it off perfectly.”

Farley says, “It was by far the most effective practical joke I have ever witnessed in my life.” It also added to the legacy of the Whittington brothers’ 935.

Over the course of the afternoon at Willow Springs, Meyer lapped in his 935. I got in a bunch more laps, and Meyer’s son Evan took the car out. Nobody ever drove the car in anger, and it never misbehaved. Mechanically, it seemed bulletproof. When the sun began to set, we shivered in the oncoming darkness as our photographer shot the car with its lights on against a glowing sunset.

I ended up in a quiet motel room clutching a Jack Daniel’s on the rocks in a plastic cup, bewildered by this experience. I could not get the sound of the Porsche’s exhaust note out of my head. The smell of the rumbling flat-six remained fresh in my nose. You have to hand it to a guy who brings a priceless Porsche out to the track so his friends can drive it. And you have to hand it to a car with a story this good. As Meyer says of his Porsche, “It did what it was built to do: win.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos