How El Niño May Test the Limits of Our Climate Knowledge

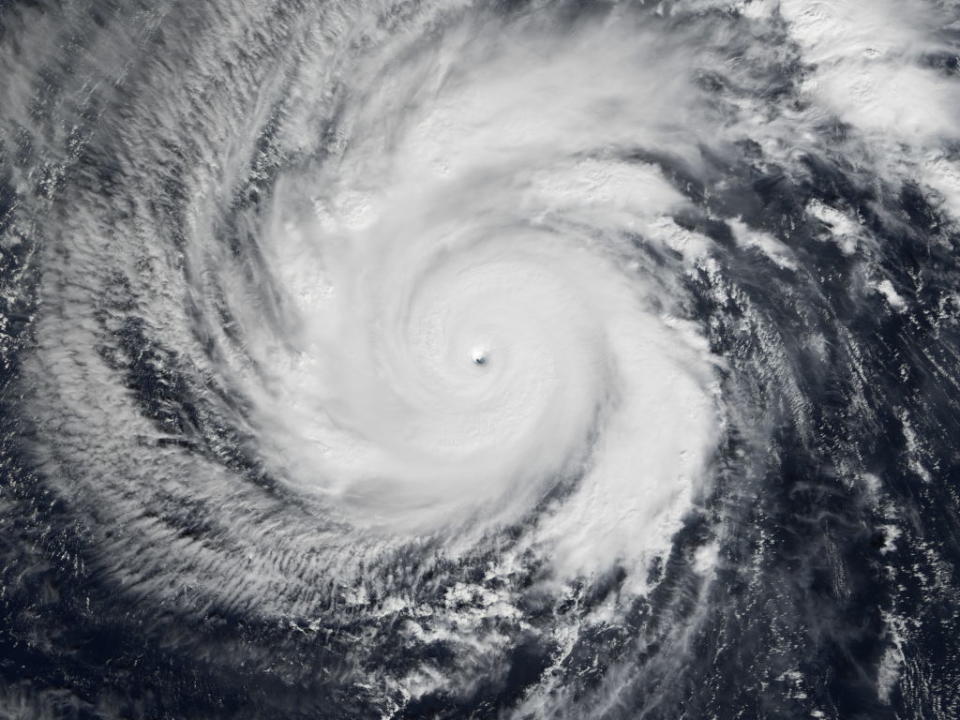

Typhoon Faxai was a Category 5, super typhoon which lasted between December 13 - 25 the 2001. Credit - Universal History Archive

After three years of La Niña, the pattern is forecast to weaken in the coming months, and the start of an El Niño is possible in summer or fall 2023, according to seasonal forecasters. Such a transition would likely have multifarious impacts on weather worldwide, as past El Niños have. But the increasing impact of human-induced climate change places the possibility of an El Niño now into a new context—and raises some new questions.

El Niño and La Niña are the opposite phases of the so-called El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon, in which the normally cool waters of the equatorial eastern Pacific ocean warm up (El Niño) or cool down even more than usual (La Niña). But these events have global ramifications: a typical El Niño causes drought in Indonesia, Australia, southern Africa, and India; rainy winters in southern California and dry ones in the Pacific Northwest; quiet hurricane seasons in the Atlantic but intense ones in the Pacific; and other consequences around the world.

In short, ENSO is like a natural form of climate change. But ENSO is natural, while global warming is human induced; one goes persistently in one direction, the other goes back and forth every few years. That said, ENSO and global warming are connected in a few key ways.

ENSO noticeably affects the Earth’s global average surface temperature. A major El Niño event can raise it by as much as a few tenths of a degree Celsius (or around half a degree Fahrenheit). Since our average temperature has already increased by 1.2 C since pre-industrial times, a sufficiently major El Niño event could even push the planet, temporarily, past 1.5 C warming. International negotiations have aimed, with increasing desperation, at reducing greenhouse gas emissions fast enough to keep us below that threshold, and the IPCC special report in 2018 described the consequences of crossing it. Would it then be too late—could ENSO make 1.5C warming a done deal?

In the most important and meaningful senses, no. When we talk about global warming, we are talking about changes in long-term averages, not the kinds of year-to-year fluctuations that ENSO causes. Those who deny or downplay climate change like to elide this distinction to confuse. By measuring the change in temperature starting at the year of the last big El Niño event (2015), when it was temporarily above the long-term average, they can then make the totally misleading claim that there has been no warming since that year. So it would be equally disingenuous to interpret a short-term warming due to an El Niño at present as representative of the long-term trend, and claim that we have passed 1.5C warming because of it.

Nonetheless, it’s telling that we are close enough to the 1.5C warming mark to start thinking this concretely about it—and the prospects of cutting emissions fast enough to stay under the 1.5C target are poor, El Niño or not. Global warming has gone from the predicted future concern it was in my youth to a very real and present one.

Accordingly, governments and businesses are recognizing that we have to adapt to the climate change that is already here, and the more that is coming soon. For example, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed a rule that would require public companies to disclose their climate risks. And here, uncertainties related to ENSO may play another role, one that challenges our scientific understanding.

Our climate models predict that, as the planet warms due to increasing greenhouse gases, the tropical Pacific will shift towards a long-term average state more similar to El Niño than in the past. All else equal, that would lead us to expect the kinds of future impacts we’ve historically associated with El Niño events to occur on a more regular basis: more active Pacific typhoon seasons and less active Atlantic hurricane seasons, for example, or a wetter Los Angeles and drier Seattle.

But over the last 50 years, notwithstanding the substantial greenhouse gas-induce warming we’ve experienced, the Pacific state has actually gone towards greater incidence of La Niña, the opposite of what the models predict should have happened.

It’s possible that the disagreement between models and observations is just a fluke. 50 years is still a short time to assess trends in a system that, like the tropical Pacific, is prone to big, erratic year-to-year fluctuations. But more climate scientists are starting to question whether the models may be fundamentally wrong about the tropical Pacific’s response to warming.

If so, it would not invalidate our big-picture understanding of climate change; the planet would still be warming due to human emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases, and we would still need to stop burning fossil fuels. But it would mean that our expectations about many specific regional manifestations of climate change may be wrong, at least in the next few decades. Compared to current projections, future Atlantic hurricanes may be more frequent, Pacific ones less so, and drought in the southwest US more persistent, while southeast Asia, northeast Brazil, and southern Africa would trend more towards wet conditions than the dry ones currently projected, to take just a few examples.

To make things even more complicated, our current understanding suggests that while the the models could be wrong now, the reason for that could be transient, so that eventually—maybe by 2100, maybe later—they’ll be right, and the trend towards El Niño-like conditions will materialize. But even if so, this isn’t particularly helpful for climate adaptation efforts with time horizons of decades.

Over the next month or two, it will become clearer whether or not we are likely to have an El Niño event in 2023. The direction of longer-term change in the tropical Pacific will take longer to determine. More research can hope to increase our confidence over the next few years, as the scientific community has begun to focus on this problem more seriously than in the past. Because what happens in the Pacific ripples so strongly around the world, the answer is critical to preparations for the coming decades on our warming planet.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos