Endurance Racing with Smart People–and Us

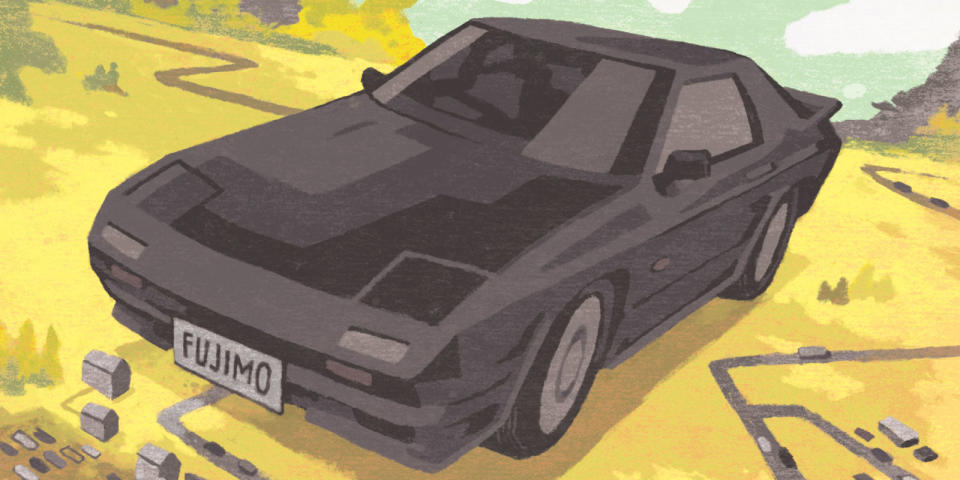

THE LICENSE PLATE on the Mazda read "FUJIMO." Standing in the paddock at Mid-Ohio, I had no idea what this meant, so I pulled out my phone and Googled. Turns out it's an old military acronym. One that, like so many, requires an F-bomb: "F*** You, Jack, I'm Moving Out."

I looked at the car. It fit.

The Mazda was black, a multi-time NASA winner, and second-generation RX-7 with its roll cage and interior painted white. It looked like Death's tuxedo. An ancient GM 3800 V6 sat under the hood, its water pump even with the shock towers. There was enough room to lean in and stick your head in front of the motor, so I did. I also burned my nose on the radiator because, like young children and celebrity stalkers, I should apparently not go near hot things without adult supervision.

All of this was last fall. I went to Mid-Ohio to drive the Mazda with American Endurance Racing. AER specializes in amateur enduros-long road races designed to break cars and people. You strap in for hours at a time, pushing the limits of fuel capacity and that floppy Egg McMuffin you had for breakfast, attempting to rip off consistent laps in 100-mph traffic without grinding your brain to mush. There are pit stops. You give the car to another driver, rest, then get back in.

Most people drive one car in an enduro. Using your rest time to race a second is less than smart. Three cars is generally seen as epically dumb.

I went for three.

AER is run by a handful of guys from the East Coast. One, Seth Siegel, told me they decided to start a race series over beer one night, a lark. It kicked off in 2014. Some 700 drivers have since taken a flag with them.

"We wanted a friendly middle ground between ChumpCar and pro racing," Seth said. (Note that he excluded the big dogs of American club racing, NASA and the SCCA, which are about as friendly as a Disposall with your arm caught in it.) AER's big idea was running real race cars on street tires, to reduce cost. Also shockingly low entry fees and an effort to vet drivers before taking their money.

It worked-tires that slide and last forever, close racing with trustable traffic. Mid-Ohio attracted a host of cars, from old Spec Miatas that smelled like feet to a pair of ex-IMSA Porsches driven by pros Will and Wayne Nonnamaker. Last summer, R&T contributor Jack Baruth emailed and invited me to drive the RX-7. He was sharing the car with its builder, a quiet Ohio man named Matt Johnston. (Matt's most infamous project: shoving a Roush Yates NASCAR V8 into another RX-7. Matt's nickname: Tin Man, because hr's a sheetmetal worker. Matt himself: mad genius.)

Next, one of the magazine's web editors, Travis Okulski, helped me rent a seat in a 1993 BMW 325is. And the week before the race, I discovered that former editor Webster and associate publisher Jason Nikic were running a BMW Spec E30. Because they are nice people, they let me horn in.

I met up with Travis at the track.

"Why," he said, "are you doing this?" His tone indicated that he thought my plan was stupid.

"Why," I said, "am I doing this?" My tone indicated that I thought my plan was transcendent. I was also on three hours of sleep and cackling like a doofus, because that's how amateur enduros work. Whether it's travel or fixing a broken car or late-night margaritas, you never sleep.

You strap in for hours at a time, pushing the limits of fuel capacity and that floppy Egg McMuffin you had for breakfast.

Next to racing, shut-eye's overrated anyway. AER runs split events, usually two nine-hour races per weekend. Saturday gave me E30 and Mazda and four stints at the wheel. Sunday produced all three cars and I don't remember how much driving.

I blame brain fade for the memory problem. Also the fading of everything else in my body. The RX-7 had 250 hp, fat tires, no power steering. Matt likes 20-minute sprint races and a knife-edge chassis; the Mazda was thus blindingly quick for the first 30 minutes of each stint, because that's how long my reedy arms could tame the oversteer before going to pudding. The car felt like a half-scale Dodge Viper with more ingrained Eat Me. I wanted to marry and take its name. (Doodle it in the margins of a notebook, surrounded by hearts: Mr. Sam FUJIMO.) We finished second in class in the first race, killed a wheel bearing the next day while running up front.

Enduros: all different, all the same. Traffic, rain, sun, pounding around the track. That old swampy-pants feeling, where your fireproof long johns are sweat-soaked for days. Every muscle burns, but you keep driving, because what are you, dead?

The Spec E30 ran well. The other BMW snagged a podium. Each was helmed by a friendly team that reminded me of an old adage: With club racing, what you're doing is never so important as the fact that you're doing it. Not home, sitting.

After a stint in the E30 on Sunday, I pitted, leaped out, and sprinted toward the Mazda's pit stall. Minutes to strapping in again. Lungs afire. As I ran, a bystander yelled out.

"What's the rush?"

"I can't stop!"

It was half laughter, half plea. I love this stuff, but I'm not sure I could do it for a living. The sport works too well as a blow-off valve for normal life. The diabolical focus of a sprint race. The odd bubble of an enduro, where your internal clock melts and you steep in bleary exhaustion. That withered feeling at the checker, where more driving, ever, sounds like torture.

And then, at the end of the season, you pack up and leave the track. Same every year. Fall air so crisp it pricks your ears. Winter coming. A rest from such nonsense.

I miss it already.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos