The Fight Against Smog Starts With Mr. California

Frank Lanterman grew up in a family obsessed with air. His forebear Jacob Lanterman had come to the Crescenta Valley, north of Los Angeles, in the late 19th century as part of a wave of European Americans from the Upper Midwest who traveled to the Verdugo Mountains, literally in search of a healthier atmosphere.

This story originally appeared in Volume 23 of Road & Track.

“His grandfather came here from Michigan with his family because of some tubercular issues,” says Julie Yamashita, the archivist at the Lanterman House, a museum in Frank’s childhood home in La Cañada Flintridge, near Pasadena. “That was something very common here. They would come for the air and the healing powers of the California sun.”

In 1915, Frank’s father, Dr. Roy Lanterman, hired L.A. architect Arthur Haley to adapt his innovative practice of designing naturally ventilated urban apartments and office buildings to a single-family country house. The result, El Retiro, was a Craftsman-style cement home organized around air circulation. Lanterman’s family was equally obsessed with the automobile. “They had a three-car garage in 1915 before most people even had one car,” Yamashita says. Being fans of all things circulatory, the Lantermans preferred steam power over electric or internal combustion, maintaining a 1922 Stanley for decades. Frank and his brother, Lloyd, even patented oddball steam-power technologies.

These passions collided as suburbanization swept in after World War II. The Foothill Freeway, among the region’s last major highway projects, was potentially slated to run through the center of the Lantermans’ town. As major landholders, they were likely concerned about the effects that roadways and pollution might have not only on their beloved air but also on their property values. This was the catalyst for Frank Lanterman’s trailblazing career fighting for vehicle-emissions control and, consequently, how California became what it remains today: the state pushing the entire automotive world in setting stricter emissions standards.

In 1950, Lanterman won a seat as a Republican in the California Assembly, a job he would hold for 14 consecutive two-year terms, until nearly the end of his life in 1981. While he entered government as an anti-spending deregulator, bent on garnering Colorado River water rights to benefit his family’s company, he soon tackled issues at odds with party orthodoxies. He is best known for his legislative success in defending the rights of people who were institutionalized and others with developmental disabilities, work that continues under his foundation.

Lesser known is his activism as a lawmaker who helped California pass the nation’s earliest clean-air regulations regarding vehicles. Not long before Lanterman’s election, the 1947 California Air Pollution Control Act had created Air Pollution Control Districts throughout the state at the county level to combat the overall problem of contaminants. Pioneering local researchers—including A.J. Haagen-Smit, a scent scientist known as the father of air-pollution control—were finding and publicizing that L.A.’s choking yellow-brown haze was caused in part by the photochemical transformation of elements in tailpipe effluent.

In 1953, Governor Goodwin Knight called a special conference on air pollution, where the attendees agreed: “Smog is the number one problem of Los Angeles County, and all should join in fighting it.”

Lanterman did just that, digging for solutions that, given California’s auto-centricity, wouldn’t stymie residents or the local economy.

He studied recent aftermarket innovations focused on removing tailpipe emissions at their end source, and in January 1955, he was among three sponsors of a bill, A.B. 3574, that appears to be the nation’s first official attempt at regulating automotive emissions. It recommended that, by 1957, “no motor vehicle shall be operated upon the highways unless it is equipped with a muffler of a type approved by the department as being sufficient to remove air pollutants in a manner consistent with reasonable air pollution control practices.”

That bill did not pass. But in the Sixties, Lanterman supported similar bills that did pass, resulting in laws requiring that mufflers and crankcase blowby devices—together they addressed the sources of most smog-causing vehicular hydrocarbon emissions—be fitted to all new vehicles sold in the state and retrofitted to many older ones. Though the scientific community strongly supported such actions, automakers and the petroleum industry resisted them, making often specious public claims and slowing their progress. In 1965, Lanterman voted for what would become the first state laws setting standards for tailpipe emissions of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide.

Lanterman continued his effort to reduce emissions. He introduced a bill in April 1967 to centralize air-pollution control under a state board, instead of often lax individual counties. In 1970, he co-sponsored more than a dozen air-pollution bills, most of which became law, making automotive emissions-control equipment, inspections, and testing standards more stringent. The legislation also addressed fume evaporation in gasoline and regulated emissions from nonvehicular sources such as agricultural waste. (Another one of the measures, which passed in the Assembly but stalled in the Senate, would have banned the use of lead in gasoline, a move the industry long opposed that would nevertheless happen a few years later.) A pair of successful 1974 Lanterman bills continued to strengthen emissions standards for new vehicles sold in California, focusing on powertrain octane ratings and manufacturers that were in violation of testing procedures.

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW

Hearst Owned

Lanterman was especially vocal in railing against automakers’ slow-walking, excuses, and prevarications in getting emissions-control innovations to market. “We’re going to have to take some overt steps,” he warned representatives from Chrysler and Ford at a December 1967 hearing on the technologies. “We’re going to have to protect ourselves come hell or high water.”

Not all his ideas would endure. In fact, some seemed like downright stunts. In 1970, he introduced a bill that punished higher-polluting engines by aligning car registration fees with compression ratios—the higher the ratio, the dirtier the burn, and the higher the cost. A 1975 attempt at reducing emissions involved a failed measure to require all cars with an internal-combustion engine sold in California to use stratified-charge fuel injection, like the Honda Civic with the unorthodox catalytic-converter-free CVCC motor.

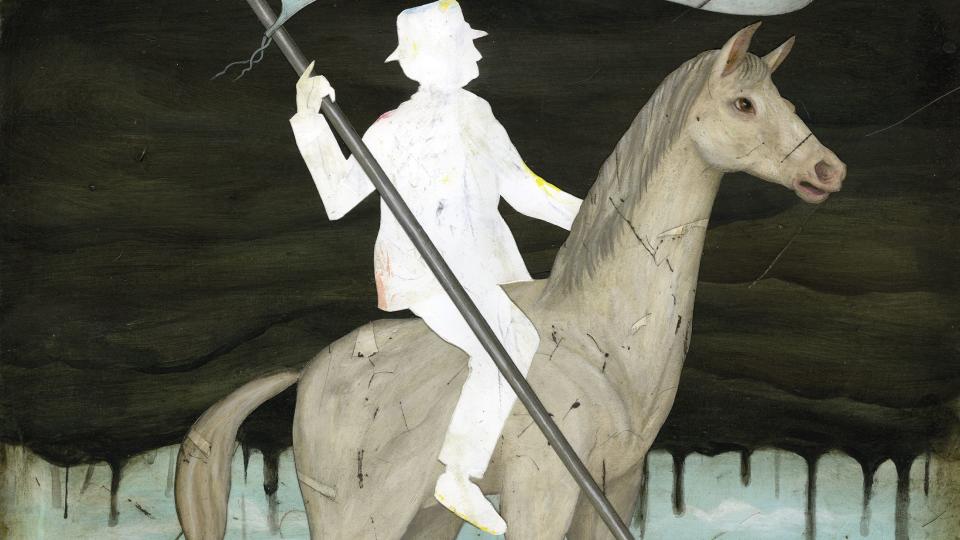

Lanterman’s fetish for steam power also returned, with bills in the late Sixties and early Seventies to fund experimental, unwieldy, and ponderous steam-powered cars and buses. In his office he kept a plaque emblazoned with an image of a covered wagon and the words “Fight Smog, Buy Horses.”

Eventually, federal legislation obviated the need for some of Lanterman’s campaigns, though California still sets its own more stringent emissions standards pursuant to the federal Clean Air Act.

In many ways, Lanterman’s is a classic L.A. story. “He started out as a performer. He was an organ player, and he wanted to be a star,” Yamashita says. “He went to Australia to do that. And when he came back, he kind of settled down. But he never got that out of his system. He had that show-business kind of thing going on.”

Lanterman’s theatrics seemed to elicit equal parts ire and admiration from his peers in the legislature, who nicknamed him “Uncle Frank,” “the Workhorse of Sacramento,” and “Mr. California.” When a section of State Route 2 opened near Lanterman’s home in 1978, it was officially christened the Frank Lanterman Freeway. Though this is among the highest honors a Californian can attain, Lanterman was not amused. “Frank hated it,” Yamashita says.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos