We Found a Classic American Car Show in a Remote Swedish Mining Town

The driving age in Sweden is 18, and as that magical number approached, Nicklas Holmgren accepted that his first car would be a Volvo, because of course it would be. But he pined for something big and bad and born in Detroit, preferably before he was. So in 1990, at 19, as soon as he'd saved enough money, he drove 210 miles from his home in Kiruna to the nearest big city, Luleå, and bought a 1970 Oldsmobile Cutlass. Now 47, Holmgren says his attraction to the car hit him "like a bolt of lightning on a clear day."

Holmgren's obsession with American cars may not be normal, but neither is it uncommon. On a summer afternoon in the center of most any working-class town in Sweden, parades of Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles and Plymouths course through the streets, driven by men sporting leather jackets and slicked hair. The culture has a name-raggare, typically translated as "greaser" but derived from a verb meaning "to pick up girls"-and it's turned Sweden into an unlikely museum of American cruising culture.

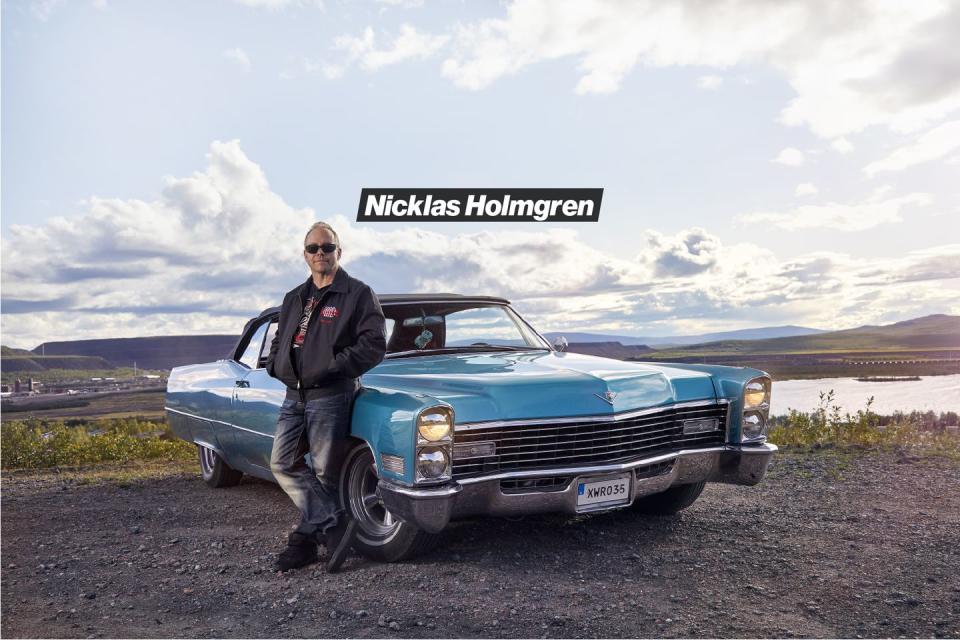

Holmgren's current ride, a metallic-blue 1967 Cadillac DeVille, is parked outside the headquarters of the Midnight Sun Cruisers (MSC), the raggare club he co-founded in 1989. The clubhouse is a two-story brick building across the street from Kiruna's ski hill. The original idea was to have a place where Holmgren and his friends could rebuild engines, drink beer, and complain about work. Within a year, there were 20 members. Today, there are 90.

Most of the members, then and now, work at Kiirunavaara, a mountain in Kiruna that contains the largest underground iron-ore mine on earth. Since its founding in 1898, the mine has produced more than 900 million tons of high-quality magnetite. "No mine, no Kiruna," Holmgren says.

Which is why the town is in the midst of one of the most audacious and mind-boggling civil transformations in history. Back in 2004, LKAB-the government-owned company that runs the mine-announced that it would have to dig deeper, rendering much of Kiruna unstable due to subsidence. If the mine were to survive, then a huge part of the community would have to be relocated about two miles away. Ever since, engineers and bureaucrats have been figuring out how to tear down and rebuild some 5000 homes and most of the town's key buildings.

This has kept Holmgren busy. He's worked on a crew that razed some of the town's oldest homes, driving an excavator and picking the houses apart carefully to preserve what can be recycled. Now he's working on relocating the E10 highway, the main route to Norway. The new road, unfortunately, points directly toward the MSC clubhouse and will soon pass within a few dozen feet of where Holmgren has parked his pride and joy.

"We're a car club; we don't care about noise and dust," says Johnny Karlsson, one of Holmgren's closest friends. He owns a paint shop, drives a pristine pink 1960 Coupe DeVille, and drums in a rockabilly band called the Stylemasters.

Over the years, MSC has added more garage space as well as a 1950s-themed bar with vinyl booths, a wall mural of the devil smoking a cigar, and the club's logo embedded in floor tile, laid by a member with a wooden leg who also built the custom chrome lights. A few years back, Australia's Wheels magazine had a contest to identify the coolest clubhouse in Sweden. MSC won, and the prize, a jukebox preloaded with 1950s rock 'n' roll, sits in a room off the bar where the Stylemasters and other rockabilly bands regularly play.

As the afternoon slides into evening, members filter in and gather. The sun, however, lingers. Summer days are extraordinarily long in Kiruna, which sits 90 miles above the Arctic Circle. For weeks on either side of the solstice, the sun doesn't set, which is how the club got its name. The winter, though, is brutal. It's frigid, of course, and dark. The sun doesn't come up for weeks.

Adrian Rönnbäck, a 27-year-old with a shaved head and a thick beard, didn't get his 1966 Sedan DeVille out until April 4 last year-and even then, there was still a light layer of snow on the roads. His "piss yellow" Caddy is from Texas, with six owners since being imported in 2014. It needs paint and has torn carpet and cracked upholstery. Beer cans and bottles litter the floor under the back seats, but Rönnbäck says he has plans. He wants to paint it matte black with a candy-red roof.

Rönnbäck works in Kiirunavaara, 4475 feet below the surface. He shows a video shot through the Caddy's windshield of his 15-minute drive from the mine's entrance into the earth, saying, "This is my commute."

There are some 300 miles of paved roads winding under Kiruna, deep enough that the average temperature down there is 78 degrees Fahrenheit. The mine's dining room-which LKAB advertises as the deepest restaurant on the planet-is often 85. So Rönnbäck might enter the mine when it's -15 degrees outside and switch on the air conditioner by the time he parks.

Achi Nurmilampi, a 50-year-old mine inspector who drives a Ford hot rod, tells us, "In the 1970s, Kiruna had the most American cars per capita." True or not, most everyone we encounter believes it. The number of classic cars in town has varied over the years, often following the mine's booms and busts. But even in the worst times, he says, the locals never abandoned their love of American iron. Popularity of specific models waxes and wanes, but Kiruna is a GM town. When editors from Bilsport, a Swedish car magazine, came to town awhile back, they said they had never seen so many Cadillacs in one city, Holmgren recalls. But the most popular classic car in Kiruna, Karlsson adds, is the 1965 Chevy Impala. "It's as usual as a Volvo," says Holmgren.

Every greaser in Kiruna tells a slightly different story about how they got hooked on the cars. Roger Lindehag was your typical teenager in 1979, with long hair and a profound love of Deep Purple. Then he went to see American Graffiti. The next day, he gave all his records to his brother, cut his hair, and coated it in grease. He's been riding with the raggare ever since. "That movie changed my life," he says. "It changed a lot of lives."

When raggare was born in the 1950s, it "caused a huge moral panic," explains Thomas O'Dell, a professor of ethnology at Sweden's Lund University. Newspapers warned of the dangers of these gangs of young men, and the city of Stockholm commissioned a report looking into what could be done. As a result of this 1962 report, Sweden passed "raggare laws," giving the police reasons to stop American cars. The whole point of raggare, O'Dell explains, was "to be seen in the biggest, flashiest cars."

It still is. During our visit to Kiruna this past summer, MSC was in the midst of the 2018 edition of its Classic Car Rundan, an annual tradition held on a Saturday in mid-August. At some point, the club's elders realized that car shows are nice, but given the choice, most people would rather see the cars moving. So MSC began a rolling trivia quiz. Between 10:00 a.m. and noon, participants cruise around Kiruna, stopping at 10 locations to answer questions such as "In what year did Henry Ford first produce the Model T?" and "Which years was the Chevy 262 V-8 built?"

We join the festivities in Nurmilampi's Ford, which has a furry brown tail hanging from its rearview mirror. It looks like real fur, but it's too long to be rabbit.

"I think it's cat," he says, surely kidding.

He's not. "It's not my cat!" he says.

We stop to pick up a case of beer at Systembolaget, the national chain of liquor stores and the only retail outlets in Sweden where you can buy beverages with more than 3.5 percent alcohol. Although the ban on drunk driving is rigorously enforced here, every classic car seems to have a case of beer on the floor in back, if not also liquor bottles rolling around under the seats. But there is always a designated driver, and nearly everyone has a personal breathalyzer in the glovebox. It's perfectly legal to drink in the car, so long as you aren't driving.

A black 1956 Plymouth Belvedere with a green top passes us, looking as if it had been pulled out of a barn after having served for decades as a raccoon hostel. Nurmilampi explains that this is a subgenre of raggare that Swedes call raggarbil. As in the U.S., it's a badge of honor among a certain sect of greasers to have a car so beat up that it invites the police to stop you. Which then allows these owners, who tend to become masters of Swedish inspection standards, to flout the authority of the cops, who are forced to admit upon closer scrutiny that the car passes muster. The one we've spotted displays a carefully curated collection of stickers, including the ever-popular "MILF Hunter."

We catch up with its owner, Micke Drugge, at the next stop. He is a welder at the mine, and on this day off, he is wearing overalls with a mesh tank top and a painter's cap with the brim flipped up. He has a voluminous fisherman's beard, sleeve tattoos on both arms, and a large horseshoe ring in his nose. "Everything," he says, "is to piss people off."

Raggarbil cars are often lowriders and convertibles, because the point is to party, and taking the top off means you can fit more guests inside. It is not unusual to see eight or more young Swedes piled into a single car as the sober driver does slow circles around town. At least until the police tell them to knock it off, at which point they cruise to another town, which is an impressive commitment to civil but social disobedience.

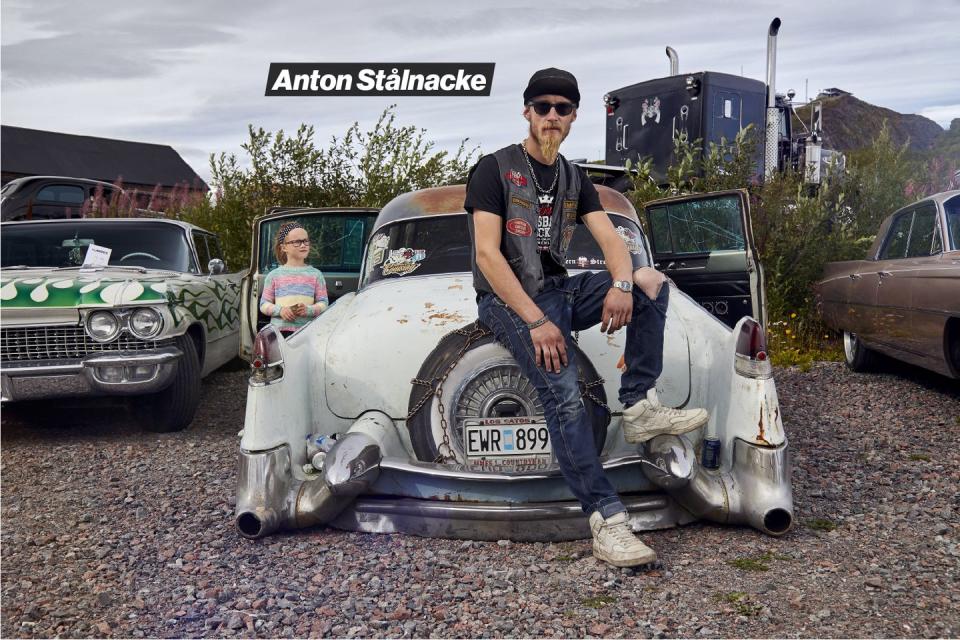

The exemplar in Kiruna is Anton Stålnacke's heavily modified 1954 Cadillac Series 62, which has many dents, a rusty roof, and an air suspension. Another nickname for cars like this, Stålnacke explains, is råttsoffa, which is exactly what it sounds like. You've got the aesthetic right when your car looks as if the squeaks in the back seat come from rodents, not springs.

Stålnacke, 25, is a mechanic in the mine's machine shop. Five days a week, he rebuilds heavy equipment 5000 feet below the surface from 5:00 a.m. to 12:20 p.m., with a 29-minute lunch, because, he explains, "If you take 30, you don't get paid."

He makes good money, and despite his car's outward appearance, both his front and back seats have new upholstery. He spent $10,000 on a sound system that fills most of the trunk. The first time he cranked the volume, every window in the car cracked. He left them all in place. He's also bolted a rare Biarritz chrome wheel-one of a set that cost a friend of his $8000-to his trunk. "I have destroyed it so it can be there," he says.

It is not uncommon to hear Stålnacke coming blocks before you see him, with up to 15 friends aboard, blasting 1950s rock or sometimes death metal. The police, he says, want him to go home. He often will, rather than accede to the Man and turn down the volume. "I say, 'I'm having a party. I can't turn it down.'"

The MSC car show set an all-time record for entries this year. The car culture in Kiruna is clearly thriving, which raises the question that nobody seems able to answer. The 27-year-old Rönnbäck asks it, apropos of nothing, late into the Saturday-night rockabilly party that caps off the day back at the clubhouse.

"Why do you think we all love these cars?"

Mostly people just say that's how it has always been, since they were kids. It's how they hope it'll always be, kind of like the mine.

He looks toward the dance floor, into the blur of whirling leather, and considers this. Perhaps he thinks about the beer and the parties and the girls and the rebellion. Perhaps not.

"I think it is because these are the most beautiful cars ever made," he says. "There's nothing else in the world like them."

From the February 2019 issue

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos