When Will Gas Prices Come Down to Earth? You May Not Like the Answer

First, the good news: despite a lot of nerve-racking volatility, the price of crude oil is expected to go on a downward trend, reversing the record levels we've seen so far this year.

The bad news: That isn't likely before 2023, and anything can happen between now and then.

Don't blame gas station owners or the president. They have less control over the situation than we'd like to think. It's a complex global landscape out there.

You may have felt a slight tingle if you visited a gas station after July 4. Whatever libations you may have consumed during the fireworks or the tinnitus that came after is not our concern. It's gas prices: They went down for the first week in months. But are they on a downward trend that will get us back to pre-pandemic levels? The answer is no, not this year.

Republicans blame Joe Biden, Democrats blame Big Oil, the Greens would like us to convert to bicycles, and in northern Connecticut, Ralph Nader is laughing at everyone. What's happening with record-high gas prices is simple and yet so complex that not one single actor deserves all the blame. Let's dive into the crude world of gasoline.

A Non-Political Explanation of Crude Oil Prices

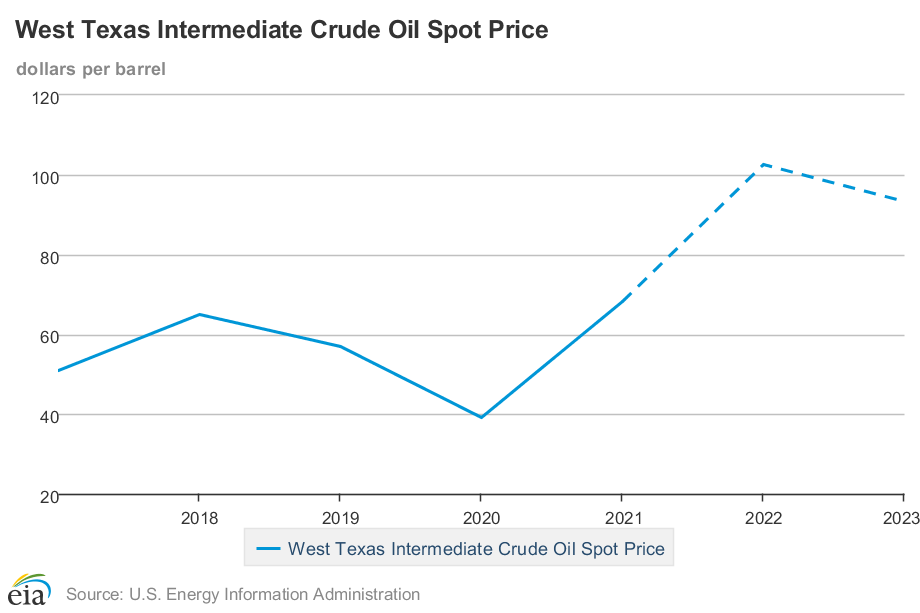

In North America, we track oil prices using West Texas Intermediate (WTI), a crude blend sourced primarily from Texas that serves as one of several global benchmarks for oil futures, or the contracts that buyers agree to pay oil producers for a barrel of crude at a specified future date. The WTI price you see quoted in the news is what's called a "front month," which refers to the futures contracts that expire closest to the current date. At present, WTI closely mirrors Brent crude, which makes up the majority of European and global oil futures.

WTI prices for a barrel of crude dipped below $100 this week for the first time since May 10, according to the Wall Street Journal's price chart. Oil began trading above $100 in the week after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in late February, when investors worried that Russia's lucrative oil reserves could be upset with potential economic sanctions. But oil prices were already rising before the war, in sync with the general uptick of the global economy since the 2020 shutdown when WTI briefly traded negative and barely rose above $40. With resurgent demand and economic activity in 2021, WTI rose into the $60s, $70s, and low $80s. It climbed again during the first quarter of 2022 and reached into the high $80s and low $90s during the weeks and days before the invasion. Crude is a huge portion of every gallon of retail gasoline—nearly 60 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Retail gas prices and crude prices go hand in hand, as everyone has watched since a gallon of regular-grade gas sank to a low of $1.77 in April 2020 and then rose to $2.85 by the end of March 2021, according to EIA records. Average prices rose past $3 last July, mirroring the rise in crude, and matched the crude spike in early March 2022 when prices soared past $4—and never went back. Gas reached a record $5 on June 13, only to trickle down to $4.77 on July 4, according to the EIA. The last time gas was this expensive (when it was $4 during July 2008), crude prices had peaked just as high as they have this year.

Crude oil has been especially volatile for the past four months. WTI prices shot past $120 early in the Russian invasion and after European sanctions blocking all Russian oil took effect on June 1. In this same time span, crude fell to the mid-$100s only to rise days or weeks later. Final closing prices on July 5 and July 6 dipped below $100, yes, but this happened at least nine times since the first spike in March. The war, record-high inflation, surging interest rates, the worry over slumping global demand from the high shipping costs that high oil prices cause and trickle into equally high consumer prices—it has been another unpredictable year, to put it lightly.

This past week, the Biden administration floated the idea of a cap on Russian oil prices, which make up close to 10 percent of the global supply. The New York Times called it a "novel and untested effort to force Russia to sell its oil to the world at a steep discount" that could "starve Moscow's oil-rich war machine of funding and . . . relieve pressure on energy consumers." It's too soon to know whether other countries will agree to such a plan.

Meanwhile, its latest forecast, the EIA predicts WTI prices will remain around $102 and then dip to $93 sometime in 2023. Futures contracts seem to agree, with contracts expiring as far out as April 2023 trading in the mid-$80s, according to Barron's. But literally anything can happen between now and then to shift that trajectory.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos