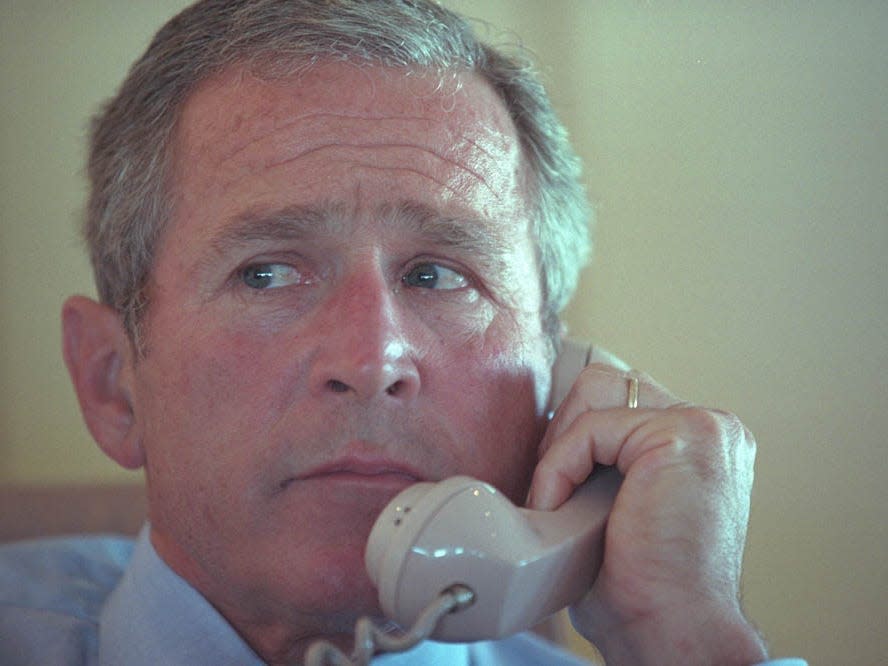

George W. Bush misrepresented our work at CIA to sell the Iraq invasion. It's time to call him what he is: 'A liar.'

Two former CIA officials spoke to Insider before the 20th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq. They gave a firsthand account of the George W. Bush administration's attempts to misrepresent intelligence and assert a connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda. In fact, the evidence assembled by the CIA suggested that no such connection existed.

One of these false connections was a supposed meeting that had occurred between Mohamed Atta, the chief 9/11 hijacker, and Iraqi intelligence agents in Prague. In December 2001, then-Vice President Dick Cheney went on "Meet the Press" and falsely claimed that the meeting was "pretty well confirmed." A 2003 CIA cable states that "not one" official within the US government had evidence that the Prague meeting actually happened. Nevertheless, it became a key part of the administration's public case for launching the Iraq invasion on March 20, 2003, a conflict that would cost an estimated 300,000 lives.

The officials' combined years of service at CIA totals up to more than four decades. Their identities are known to Insider, and are referred to below by pseudonyms due to the sensitivity of their positions. Their discussion has been edited for brevity.

Bush, Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, Lewis Libby, and John McLaughlin did not immediately reply to requests for comment.

Alice: Nobody in Washington comes out and calls Bush a liar. Everybody is too polite. They use some other term for what he did. But he lied. I want to be clear about what I mean by that. He knew what he was saying was not true. He took judgements from the intelligence community that were very uncertain, judgements that we put out there with very clear caveats — "we believe Iraq is continuing its nuclear program, but we have a low degree of certainty, blah blah blah" — he would just come out and state those things as fact. He did this over and over again. Just like Cheney saying that Mohamed Atta met with Iraqi intelligence in Prague, as a fact. When the truth was, there was a great deal of doubt about it. It was our job at CIA to stand fast, to keep those ridiculous notions under control. And we tried. But there was only so much we could do. The White House wanted a justification for the invasion. The closest they came was this alleged, and apparently nonexistent, help that Iraq gave al-Qaeda [via Atta] in bringing about the attacks. So they tried to trace any kind of contacts between al-Qaeda and Iraq.

Bob: Meanwhile, our Iraqi analysts were saying, quite truthfully, that al-Qaeda and Saddam Hussein's regime were so far apart in their ideologies — Saddam was a pure secularist, al-Qaeda was a messianic vision of a caliphate and self-consciously Islamic, at least purportedly. That is like cats and dogs, you can't mix those. Of course, Saddam knew al-Qaeda was in his country. He knew everything that happened in his country. As a matter of simply staying in power he had to know. So it's perfectly natural that he would know who was al-Qaeda and what they were up to and that kind of thing. But this was not a working relationship. It was about surveillance.

Alice: Today, people say that Bush was looking to justify the invasion of Iraq. He wasn't. What he was looking for is something different — selling points. The decision to invade had already been made, and there was not any intelligence that was going to change their opinion. So this was not an effort to justify the war. It was an effort to sell the war publicly. That's an important distinction. The Bush administration was very explicit about their Iraq obsession almost immediately when they took power.

Bob: There was a group of analysts who were looking at the hijackers. Many of us were Russia analysts — for them, the Arab field was totally new. Pretty soon it became clear that the administration was focused on this alleged meeting between Atta and Iraqi intelligence in Prague. We couldn't substantiate it. The hope was expressed pretty clearly to us, early on, that we could find something. The White House was obsessed with finding any evidence at all.

Alice: A lot of that pressure on the agency comes down through the briefers. They come back from their meetings with the president and other senior officials, give feedback. On a contentious issue you might go to a meeting upstairs on the seventh floor, with the briefers, where everybody is in the room. Once, I was writing a PDB [item for the President's Daily Brief] on what going into Iraq would likely do to our terrorism cooperation with allies. The message I got back was, the president doesn't want to hear about this. Iraq was a done deal.

Bob: They were all saying that. I mean, the US was moving our forces over to the Middle East big-time. You're not going to waste all that fuel and transport power and then listen to Saddam. British intelligence realized it first. They essentially said, "My god, these people are going to invade. It doesn't matter what we write. It doesn't matter what their own intelligence analysts tell them about the consequences. They're going to invade."

Alice: I remember just totally blocking this whole thing out of my mind. I was like, "No we can't possibly go into Iraq because that would be the worst thing we could possibly do." And then one day, I realized we were going. It was a done deal. It was a horrible thing. Because we had a real opportunity to deal a death blow to al-Qaeda, or at least get it down to a level where it would be manageable. Instead we blew it up. We created the conditions that led to the rise of ISIS.

Bob: CIA analysts wound up working on Atta for three years, because policymakers were so obsessed with him. My understanding is that it all started with one photograph of this supposed meeting he had in Prague. We got it a few weeks after the attacks. It was really grainy. Maybe it was him, maybe not. He wasn't entirely facing the camera, and there were other grainy figures around him. The folks who gave us this photo in the first place, they finally said, "You're looking for something that probably isn't there." Initially, the photo recognition team had said that there was a 60 percent chance it was him. But soon we were speculating that they'd inflated that number because of so much pressure on them. And eventually, they backed off. They said they couldn't identify who it was.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos