The Grosse Pointe Myopians: Brock Yates’s 1968 Warning to the Domestic Auto

From the April 1968 issue

Imagine it this way: The year is 1870 and you march into the velvet and mahogany office of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, sole owner of the New York Central Railroad and one of the most powerful entrepreneurs in Christendom. Your message is simple; you have investigated the long-range potential of the railroads to handle America’s transportation needs and can sum tip your conclusions with a brief statement: “Commodore, you’re in trouble.”

Now Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt was never a man to tolerate much truck from poor-mouths and crepe-hangers, and he would quickly cite you a few salient facts, to wit: in 1830, the United States had exactly 23 miles of railroad track. Now, just 40 years later, that mileage stands at nearly 50,000, and all reliable projections say the figure will increase to 250,000 miles by 1900. Having given you several seconds to digest that information, he would have had you thrown into the street.

Imagine, today, trying the same thing with the management of General Motors. “It’s like this, gentlemen,” you might begin, “I have made a studied and dispassionate examination of the future of the domestic automobile industry, and I am here to warn you that its prognosis is grim, if not totally without hope.” They would probably listen to you with a certain amount of detached amusement and then have you thrown out of a 14th floor window of the General Motors Building.

The future of the automobile as we know it is in jeopardy? Who speaks such heresy? Better that you challenge the sanity of the Constitution or the virtue of our Gold Star Mothers. Isn’t the automobile business America’s-yes, the world’s-greatest industry? Do not America’s one hundred million drivers use automobiles to travel a majority of the nearly one trillion miles covered annually in this nation? And will that distance not double in 20 years-along with a vast increase in the ranks of the driving public? Statistics boding well for the growth of the automobile flow out of Detroit like numbers popping into sight in a supermarket cash register. Ten million annual car sales by 1970-clang! Fifty-three percent of all families will own two cars by 1978-clang! Stereo-tapes to be sold on 10% of all cars-clang!

If you’ll excuse the analogy, another device that goes clang is the trolley, and the domestic auto industry just might drive its cherished product into the same dusty corner of history as the Toonerville Express unless it pays attention to its business.

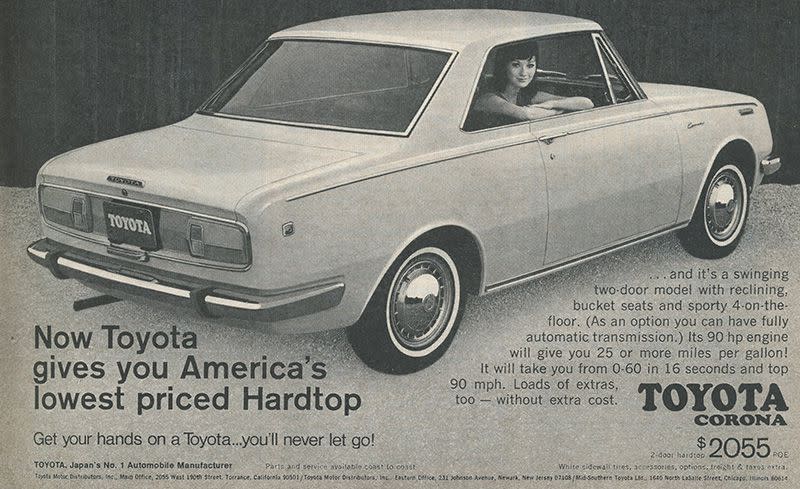

The fact is, the American automobile business is not growing like it should be. In the 1955 calendar year, the authoritative Automotive News reported that 7,942,125 domestic cars were sold in the United States. This was, according to the industry, the beginning of a rosy sales spiral that would bring 10 million annual sales by the mid-Sixties. Instead, that figure has only been surpassed twice in the past 12 years, and in 1967 a matter of 528,703 fewer cars were sold than in 1955. Simultaneously, imported car sales have risen, albeit rockily, from next to nothing in 1955 to over 800,000 per year, with a million annual sales in sight.

Being an industry with nearly as great a constitutional attachment for statistics as the daily sporting press, Detroit can fire scattershots of numbers to justify practically anything, including slumping sales. In the first place, determining actual sales is a deceiving business, because a company can use sales figures from the calendar year or the model year, depending on which set looks better. Beyond that, a given set of numbers can variously stand for the number of automobiles produced, or sold, or registered by the general public; meaning that practically any message, up to and including the salvation of mankind, can be transmitted by Detroit’s statisticians.

However, two vivid facts remain after all the ledgers have been shuffled; the domestic automobile industry is not growing as rapidly as expected, and imported cars are making shocking inroads into the American market.

Industry spokesmen steadfastly deny this, but it appears that Mr. and Mrs. America are losing their fascination with the “new” car. Financial experts claim that 5% of the national income should be spent on cars, but the general public is showing little inclination to abide by that projection. Cars have become costlier to drive, maintain, and insure, and surely the urban snarl has transformed many a shiny dreamboat from a delight into a 4-wheel curse. The notoriety directed toward the automobile regarding its lack of safety and its contributions to filthy air has doubtlessly tarnished its glamor, and it might be added that Detroit’s fumbling, often arrogant, attempts to counteract the adverse publicity have only complicated the problem.

Automobiles are becoming a pain in the neck to sizable numbers of average folks who once felt they were the only status symbols worth possessing. Now the great middle class is being romanced by the airlines (“We want everyone to fly,” coos Eastern), trips around the world, swimming pools in the backyard, second homes in the mountains, skiing trips, a chance to join a country club, and two boats in the local marina.

The dollars that used to automatically flow into Detroit’s till for a new car are going elsewhere. These burgeoning lures for expendable income have prompted millions of car owners to delay the purchase of a new car or to shift toward a cheaper import that can still be justified to the peer group on the basis of the mystique that surrounds all foreign-made goods (except Hong Kong toys).

Faced with this immense challenge, the automen are viewing the future with the distinctive brand of tunnel vision that has set their industry aside from all others for the past five decades. The provincial attitudes that pervade the Detroit scene stifle self-criticism and leave the industry’s leaders uniquely ill-equipped to face new situations, or to adjust to the shocking theory that they may become as passé as the men who committed their lives to the manufacture of buggy whips.

They face tomorrow armed with more of the same. Technology has permitted model mutations to proliferate at an alarming rate. In the past decade Detroit has produced three automotive “revolutions”: (1) the compact car, (2) the sporty car, and (3) the intermediate. In 1949 a total of 12 American car models accounted for 91% of the sales; in 1966 it took 96 models to fill the same share of the market. What has all this done for the industry? Not a great deal, except to make marketing and production nightmarishly complicated, while confusing the goals and objectives of the entire business. Divisions within the Big Three spar bitterly for their share of the market while losing sight of the external challenges, and momentary successes are often confused for long-term trends.

“The Ford Division of Ford Motor Company has had three sales bonanzas since 1960,” said a Ford executive recently. “First came the Falcon, then the Fairlane and the Mustang. When we started, we had a 23% share of the market, and now, after all that hoopla, we’ve got 20%. So what the hell did we prove?”

But the models keep belching forth: Torinos and Montegos, Javelins, AMXs, Cutlasses, Delmonts, Road Runners, Super Bees, etc., etc., and Detroit convinces itself that this activity equals growth. Simultaneously the imported car market is booming.

Precious few auto executives understand the motives for purchasing an imported car, except for empirical values like low price and operating costs, but the social implications of such undersized vehicles escape them. Most are still convinced that a majority of Americans aspire toward the ownership of a Cadillac (or replica thereof) and view the marketing and sales problems in the context of producing forgeries of this great upper-middle-class sacred cow. The idea that some of America does not yearn for bogus-Caddies is baffling to a surprisingly large number of Detroit decision makers, and in the face of the import threat they can only sputter, as one of them did recently, “Don’t call ’em imports-call ’em foreign cars. That makes ’em mad.”

Yes, the American automobile industry is in turmoil, and the technological thrashing about that has brought us high-performance cars, sporty cars, and compacts doesn’t appear to be helping the total picture a bit.

The industry has painted itself into a corner in a certain sense, because now that computerized technology has created the capability to constantly produce new models and infinite option variations for each new car, the buying public is reluctant to accept mundane standard models, and its appetite for “newness” has been stimulated to absurd heights.

The result is that manufacturers are compelled to constantly fiddle with their line-up of cars simply to maintain their position in the market. Stagnate and they are dead; misjudge the market and they are dead; produce a sales success and they merely stand still-that is the present plight of the automakers. And the stakes are enormous. One percent of the annual domestic market is approximately 80,000 units. Detroit operates with an average gross profit of $600 on each unit, meaning that the gain or loss of one percentage point in the market stands for $48 million.

Automobile men are manufacturers and salesmen. They are, for the most part, interchangeable with the men who produce ladies’ ready-to-wear and bathroom fixtures, but numbers are something they understand. Making abstract conclusions from the numbers comes a bit harder, but the importance of a sum like $48 million is eminently clear to them. They therefore look at massive numbers like this, and listen when Herman Kahn, in his new book The Year 2000, says our gross national product will have risen to $3200 billion by the end of the century (from approximately $700 billion presently). Seeing this, top-echelon executives are inclined to sit back, brush off the current state of affairs as a momentary slump, and pronounce-with some smugness-“we’ll get our share.”

“Getting their share,” as they put it, is becoming harder and harder. Each American corporation (the Big Three, with their nine divisions, plus American Motors) is spending more and more time trying to find gaps in the market that might be plugged with additional special-interest cars. This year the Torino, the AMX, the Super Bee, were all introduced to capture relatively small segments of the market, not to make great inroads into overall sales. Each time the market splinters like this, the equation becomes more complicated; because the production run is limited, distribution, styling, the choice of options, become critical. There is no second chance, because there is little permanency in the marketplace today. In fact, the automobile business is heading toward a state of affairs like the cigarette and soap industries, wherein brand names are whisked in and out of the market almost on an overnight basis. This sort of commercial confusion produces a state of mind in the car-buying public that Dr. Ernest Dichter, a motivational research expert, describes as the “misery of choice.” In other words, the selection of car models and options is so vast that a growing segment of the population apparently finds the purchase of a car a confusing and thoroughly depressing experience.

Excluded are the auto enthusiasts, who can struggle through the doubletalk and buy a car with their exact choice of options. But your neighborhood accountant, who doesn’t know a clutch from a carburetor, is defeated by the “misery of choice” to a point where he might forget the whole thing, or buy the wrong car-both in terms of his needs and the manufacturer’s projections.

Market research is a big deal in Detroit. Figures can be carted out to reveal such startling facts as how many housewives in Elkhart, Indiana, want 6-way power seats and why unwed mothers under age 21 spent 37% of their car occupancy time in the back seat. Now this sort of thing is pretty exciting-especially to other market researchers-but there is a feeling among a number of the more progressive auto executives that the effectiveness of this sort of research has been greatly exaggerated. It can be a valuable crutch for men who don’t really understand cars and their impact on the public, but for aware types, market research in heavy doses can result in nausea. “Our market researchers can produce figures to justify anything you want,” said a vice-president of one of the auto companies, “and you end up by marketing a car by the seat of your pants.”

Margaret Mead, the world-famous anthropologist, has said that the modern businessman tends to confuse data with knowledge, and commented that he would probably be a good bit more successful if he knew less, instead of more, about what his competition was up to. Her reasoning is based on the fact that his independent thoughts and actions are stifled by the sea of data in which he swims and his desire to counteract and copy the competition, rather than strike out on his own.

This is the case in Detroit. The automobile executives live in splendid isolation in the posh suburbs of Birmingham, Bloomfield Hills, and Grosse Pointe, and progress through the corporate echelons can be traced in many instances simply by an individual’s address changes. In effect, the auto industry is an immense upper and upper-middle-class family, with congregating points at half a dozen country clubs, the London Chop House, and the Detroit Athletic Club. Here information and gossip is exchanged about their parochial little world in an incessant babble that reveals a unique narcissism and widespread ignorance of the world outside.

It might be said that all Detroit cars are designed and conceived on the basis of the White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant world in which the auto executives live. They think the Electra 225 4-door is a helluva car, so why shouldn’t the rest of the world. They are 3-car families, why in hell shouldn’t the rest of the world want three cars? Their wives like cute little intermediates to drive to the hairdresser, so why in hell shouldn’t every wife in America?

“We’ve shot pictures of cars in every nook and cranny of Bloomfield Hills, Birmingham, and Grosse Pointe,” complained a Detroit advertising man. “That’s the kind of scene the industry is trying to project to the American public. In their minds, it’s paradise-the ultimate aspiration of the car-buyer. Can you imagine that?”

A superb example of the narrow-mindedness of Detroit’s executive elite is their response to Woodward Avenue-a route over which hundreds of them commute daily. Now Woodward Avenue is a microcosm of two of the major social revolutions in the nation today: the vast world of emerging, skeptical youth, and the terrible poverty and social unrest in Negro ghettos. Woodward Avenue is the greatest street-racing area in the world (C/D, June 1967), and one trip down its length is a revelation of the automotive and social tastes of the nation’s under-25 population-if you are looking. Woodward Avenue was also a major storm center of the 1967 Detroit urban riots-the most shocking and destructive in our history. And the symptoms that caused that disaster-the poverty, unemployment, social isolation, and despair of the Negroes-was evident before the violence exploded to any commuter who looked out his window.

But Detroit’s auto making community was outraged at the riots and remains oblivious, to this day, to the incalculable impact the street racers are having on the buying patterns of their cars. After all, Woodward Avenue is only a road to Bloomfield Hills, and the Negroes are rioting and the kiddies are drag racing only because they’re a little impatient about getting their hands on Electra 225s (or a smaller, racier offspring), and if America will be patient, they, the Big Daddies of Detroit, will turn the whole nation into Bloomfield Hills.

Fortune, in an August 1966 story on General Motors, commented on a state of affairs that applies to all automakers. “GM officials . . . are products of a system that discourages attention to matters far outside the purview of their jobs. And they are captives of a camaraderie that keeps them much in one another’s company-on the golf course and around the card table as well as the conference room. While this generates an esprit de corps that constitutes one of the organization’s great strengths, its effect is to insulate GM’s managers to many contemporary currents of thought.”

Businessmen are pragmatists by nature, and because the ones who run the auto industry are paid fabulous salaries and demand great respect from their underlings, they exude a depressing penchant for cockiness. In Detroit, everybody talks and nobody listens, and therefore harsh self-examination of the industry’s position regarding electric cars, smog, safety, and the need for cars by future generations does not exist. There are rote replies to all challenges (“The electric motor is 20 years off, and it’ll never be able to do the things our present internal combustion engine can do.” Period.).

Detroit executives remain confident that they are thinking at least five years ahead of the public’s tastes and that very few car buyers know what they want. They are certain that if they have made any miscalculations about the quality, design, or functions of the cars they provide, they have been only temporary and that slumps in sales are attributable to government meddling, an unhealthy economy, or the citizenry’s churlish refusal to accept what’s good for them. For the most part, they stand by the statement made by C. F. “Boss” Kettering, “It isn’t that we are such lousy car builders, but rather that they are such lousy car customers.”

The “lousy car buyers” are making trouble, no question about that. Aside from shirking their duty to the industry (and America) by not buying enough new cars, they are evidencing weird purchasing habits that are causing dealers across the nation to scream in anguish. Although it still exists in much of rural America, brand loyalty is dying in the urban centers. High-volume, high-pressure dealerships operate without concern for long-term customer loyalty, and the old-time “Ford man” or “Chevy man” is becoming a rare bird. In addition, the proliferation of brand names has diluted the impact of old-line company names. For example, the Charger is sold as a Charger, not a Dodge, the Thunderbird as a Thunderbird, not a Ford, etc., and this tactic has diminished the pride of ownership that people enjoyed in less-complicated days.

A high-ranking automobile advertising man says, “The industry has become a retail store, an automotive supermarket. It has lost its excitement, its glamour, and its dignity.” This becomes evident to anyone who enters the frenetic, den-of-thieves environment of the big-city auto dealership. Here cars are sold like discount television sets, and it is a world in which the buyer is as sure to get fleeced as a yearling sheep. “No wonder purchasing a car is an upsetting thing for the average guy,” said one dissident automan recently. “Here is this hustler who practices selling cars 365 days a year, and you expect to go in once every two years and con him into a good deal? Fat chance.”

Richard Munro Williams, an expert on auto retail methods, claims that only 1500 of the nation’s 27,000 dealerships (a decrease of 3000 outlets in recent years, by the way) are “system houses”-whose razzle-dazzle, highly formulized, often unscrupulous sales methods were outlined in the November issue of C/D. What’s more, says Mr. Williams, only half of them are dishonest. Isn’t that wonderful? Only 750 dishonest dealers in the ol’ USA, although Mr. Williams fails to mention that many of the crooks are running some of the biggest agencies in the nation.

This incessant strapping that America’s car buyers are taking, in terms of shadowy interest rates, deceptive trade-in allowances, bad service, poor quality control, plus the tasteless, trite advertising, has knocked the bloom off the new-car flower. What many automen fail to realize is that the American public has been subjected to this dismal behavior for 20 years-ever since the end of World War II-and a great percentage of them are getting either completely inured to, or totally suspicious of, the entire low-comedy fandango of “Inventory Sales” and “Special Discounts at Uncle Ralphie’s.”

It used to be that the appearance of the new cars in September and October was greeted by the American public with an enthusiasm reserved only for Christmas and the World Series. But times have changed, and the crowds that turn out to gape at the new models diminish annually. Yet Detroit and its hand-maidens in the dealerships across the nation are convinced that the entire post-war bonanza can be recaptured if only the banner headlines are a little bigger, the paints a little brighter, and the “deals” a little better.

And all the while, America yawns.

There are, most surely, exceptions. The Pontiac Division of General Motors is one of the great success stories of the past decade and today stands as the most creative, exciting, and commercially buoyant of all the domestic car builders. While most manufacturers are treading water, Pontiac is doing swimmingly in the marketplace, with over 800,000 sales likely in 1968. That is amazing, when one considers that its basic V-8 engine-the one that accounts for a lopsided percentage of its sales-has been around over 10 years and that Pontiac has the hottest performance image in the business although it hasn’t had a car on any race track since 1963!

Pontiac has broken dozens of sacred GM tenets of marketing in the past few years and has inspired a good deal of grudging respect throughout the industry and unabashed jealously from its immediate rivals at Chevrolet and Oldsmobile. By relying on sex, glamor, imaginative advertising, and a sporty, youth image second-to-none, Pontiac has managed to create an aura of excitement about its cars that no one has been able to duplicate. The marketing philosophy behind Pontiac and the influence of its brilliant General Manager, John Z. DeLorean, is a story unto itself but can be summed up in a statement by one of its most respected and innovative advertising executives. “Buying a Pontiac for most guys is like him thinking about making his neighbor’s wife. He probably won’t do it, but he thinks about it a lot.”

Luring your neighbor’s wife into the sack is a long way from the “Youngmobiles” and the “Daring, Dynamic, Different” bromides that are being issued elsewhere in the industry, and a good many timid souls in Detroit are savoring the day when the legions of powerful gray men in the General Motors executive suite tire of Pontiac’s shenanigans and stomp on DeLorean and his outrageous division.

But that is unlikely. There is a suspicion that the management at General Motors cares little about how their Division General Managers sell cars, only how many they sell. In other words, so long as the Corporation’s total share of market rises or remains stable, there may not be a great deal of concern about who sells the most among the five divisions. An exception to this is Chevrolet, the flagship of the fleet and the traditional sales leader. If it were to lose its number-one spot to archrival Ford, heads would surely roll, but otherwise nobody in top management may much care whether Olds beats Pontiac, or vice versa, so long as the cash register keeps clanging.

This attitude tends to stimulate intramural warfare and to obscure the total, long-range trends of transportation in the United States. While everybody in Detroit grapples for the one-percents of the automobile market, they remain oblivious to the effects of mass transit on future car ownership; of the urban sprawl; of the constantly changing social attitudes, and of the fact that the electrical, chemical, and aerospace industries stand as great rivals on the transportation horizon. It is interesting, for example, to note that Herman Kahn, in The Year 2000, mentions that “. . . in 1937 a [U.S. National Research Council] study totally missed not only the computer, but atomic energy, antibiotics, radar, and jet propulsion, nearly all of which had been around in principle and waiting for development.”

Kahn also notes that in 1957 it would have been impossible to convince a “scientifically knowledgeable audience” that a Polaris submarine missile system could have been produced in a decade. Nevertheless, by 1967 no less than 41 Polaris submarines were operational, meaning that six major, seemingly insurmountable technological problems had been solved.

And yet Detroit bustles onward in its Ike and Mamie good-life syndrome, convinced of its perpetual position of preeminence, not even pausing to question such unsettling things as computerized, electronic vehicles or underground transportation networks, and other ultra-sophisticated, mass-transit systems. After all, America has to be told about the glories of Bloomfield Hills, Birmingham, and Grosse Pointe.

“The gingham dog and the calico cat,

side by side on the table sat . . .”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos