Honda's Pro IndyCar Racing Sim Gave Me a New Level of Respect for the Indy 500

If you get your run right, a four-lap Indianapolis 500 qualifying attempt looks deceptively simple: Hold down your right foot for about three minutes, turn left 16 times, and don't lift. Make a small mistake, and you ruin the run; make a big one, and you might find your car crashing onto a straightaway so hard that it dents the track surface. In my dozen or so laps on Honda's new driver-in-the-loop IndyCar sim, I made four big mistakes. Three led to major crashes. It all gave me a newfound appreciation for what drivers face at the Brickyard.

Indianapolis is an intimidating place, even for the people who race there every year. Alex Palou, the reigning IndyCar champion and one of the top 10 or so drivers in all of auto racing right now, is not immune. The 2023 pole sitter, he is one of four drivers ever to complete a four-lap qualifying run at an average speed over 234 mph. As he told R&T after securing his title last year, he has never wanted a feel for those speeds from outside the car. He has made sure not to get a view of the cars flying through the corners from a spectator's perspective.

"I know it's fast," Palou said. "That's enough. I don't need to see it."

Unlike Palou, I have seen what an IndyCar field looks like through Turn 1 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. I first saw the track in person in 2022, long after I first saw the race on TV. I think about it often. It looks impossible—not just the speed, but the way drivers navigate traffic at those speeds. I have seen packs of NASCAR stock cars at Daytona from the main grandstand, top-level IMSA prototypes winding through traffic in the overnight hours of an endurance race from the rolling hills of Road Atlanta, and Formula 1 cars navigating the most technical parts of the Miami Grand Prix circuit from the fences. The 33-car field driving through Turn 1 at IMS is the one that sticks in my brain, the one sight in the entire automotive world that feels downright magical.

I already know I will not get a chance to run 239 mph into Turn 1 in an Indy car anytime soon. Fortunately, Honda's new driver-in-the-loop simulator doesn't have the high stakes of real life. After all, when you crash, it stops simulating motion.

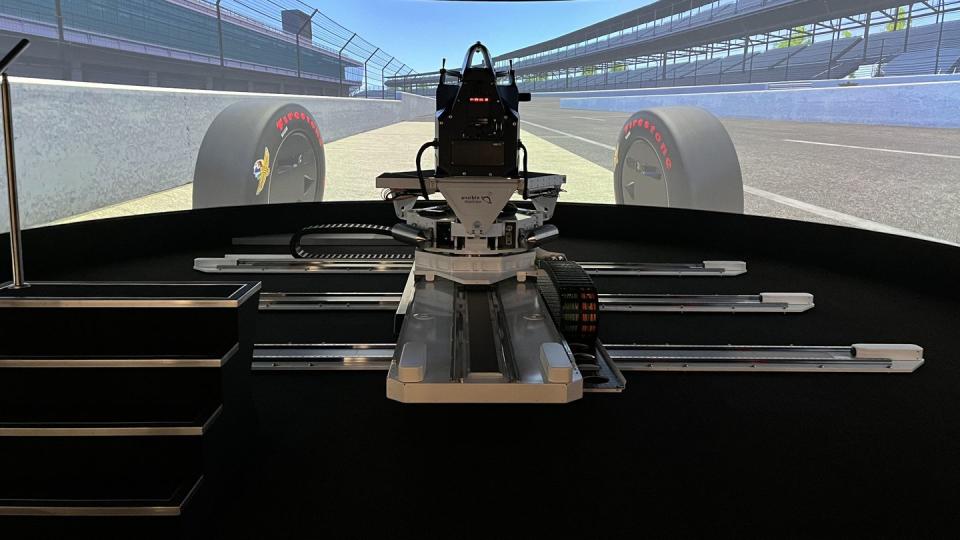

The sim is a new model, a replacement for a frequently upgraded unit used from 2013 to 2023. This one features many complicated and proprietary systems that Honda Racing Corporation USA staffers were not eager to discuss on the record. It integrates a multibody vehicle-dynamics physics simulation software with hardware that simulates pitch, yaw, and roll on the chassis, among other forces within the car itself that may be more familiar to at-home sim racers. For an amateur driver like me, that translates to an exceptionally immersive sense of speed and movement matched by a hyperrealistic model meant to simulate the real engineering challenges that drivers and teams face on the track.

That delivered a level of intensity unmatched by any sim rig I had experienced before. The unfamiliarity took my plan with it. None of the hundreds of qualifying runs I'd seen at the speedway were of any particular help, not unless I could muster the skill to follow the Hélio Castroneves line flat out while getting up to speed with the concept of the simulator itself.

It starts with a staircase, then a climb into a Dallara IndyCar chassis used as the cockpit. (Unlike Multimatic's similarly massive simulator, Honda's system is currently used only to simulate racing cars and track-only demonstrators.) After stepping over the halo (which I later learned could simply be opened with the press of a button) and into the tub, I start to feel nervous. The whole cockpit then moves from a staircase at the edge of the wraparound screen projection to its position in the center.

I already know this will be a challenge when I'm tasked with getting the car rolling. I am the first of four journalists to get a shot at the sim, and I confidently assume that I can operate a hand clutch with minimal instruction. I stall a few times, bringing back rich memories of the first time I drove a manual. Eventually, I'm given the useful instruction that I cannot destroy a fictitious clutch. I drop it harder and at higher revs, spinning wheels on my way out of the pit lane.

Immediately the weight of the steering stands out. The modern Indy car does not have power steering, nor does it have a suspension designed to keep the driver comfortable. Keeping the wheel straight is an upper-body challenge. Turning in takes more force than you expect, far more than in a road car without power steering.

The engineers running the simulation would later reveal that this is 60 percent of the actual force drivers deal with.

That six-tenths force is intense. I have seen the wearing treads of the front tires on my road cars enough to know that my steering inputs are too harsh; when I compensate for the weight of the steering, they get harsher where they should be smoother. Still, I get up to speed by lifting on turn-in before each apex, and I soon feel comfortable trying to hold it flat into Turn 3.

Immediately I make a big mistake. I am too low on exit, nowhere near the wall that would let me gracefully rotate the car with less steering input. I overcompensate on the steering wheel, and soon I realize that the car is about to spin violently back into the outside wall. The sim cuts instruction to the sled holding the tub. I watch helplessly as my virtual race car slams into the wall at weekend-ruining speeds.

For all the intensity the simulator provides, the crashing doesn't come with any fear, just disappointment. I am well aware of everything I did wrong, but that knowledge got me no further to the Scott Dixons and Josef Newgardens of the world. In my frustration, I struggle to get rolling again. It's rough.

Once I am back in the virtual warm-up lane, I let myself become completely immersed. This is my shot, and I am going to complete at least one strong lap. I build back the nerve to go flat out into Turn 3 again, holding down my right foot with the powerful, dumb sort of confidence that can come only from seeing more talented people do the same thing. I navigate all four corners flat out this time, relaxing and letting the car carry itself all the way up to the wall on exit as it is set up to do.

Or, at least, I think I do. I would later realize that I could have been much faster if I'd used more of the ample space between my right-side tires and the wall. From outside the sim, the wraparound screen seems to give plenty of information for a driver to ride as high as they want. From the cockpit, all I see are walls closing in alongside me as I am driving above 230 mph.

My next mistake is a classic. I touch the inside of the curb in Turn 3, taking the car lower than it is meant to go. I try to countersteer quickly, but the car is already unsettled, and I am again in the same wall. I restart and waste no time getting back up to speed. Within two laps, I see a 231-mph average on my steering wheel. Good, but not the times set by the engineer who runs the simulator in an earlier demo.

I keep my foot down over a handful of more comfortable laps, but I lose speed somewhere as I fall into a groove. I settle around a 229-mph pace. In this year's field, over four laps, that would be good for somewhere between last and did not qualify. Seeing that number encouraged me to try a more aggressive entrance into 3, turning in later and harder.

I hit the curb again, but this time I react more quickly. Knowing that the car will want to wash back up to the wall on its own, I give one sharp countersteer toward the wall, then another, and finally I try to hold the wheel steady as the car and banking handle the rest. It is not quite as beautiful as the actual save that race runner-up Pato O'Ward had in Turn 4 during the actual Indianapolis 500 a day later, but it keeps the car out of the wall.

In that moment, I feel immortal.

That moment lasts all of 40 more seconds. A steady run along the racing line in 1 and 2 is not easy, but I feel confident in my speed heading into 3. For this final lap, I attempt the same line, sure that I'm ready to handle what might go wrong.

I am, of course, incorrect. My run in Honda's simulator ends with a third crash in the same corner.

For drivers preparing to run an actual IndyCar or IMSA race, what follows afterward is a crucial step. Upon exiting the sim, an HRC US engineer shows me steering traces over my best laps. They are, predictably, too harsh. I am turning in with too much force and not getting close enough to the wall on exit, asking too much of the car's mechanical grip in two places and scrubbing away speed. The engineer compares my traces with the measured and artful inputs of Takuma Sato, illustrating how easily a two-time 500 winner navigates the same four turns that vexed me.

Professional drivers would review that information, take those notes, and change their approach for their next time at the wheel. I instead give my notes to the other journalists, as if they were my teammates getting into a car we shared in an endurance race. Nobody comes close to Sato's benchmark, but every would-be driver leaves with a new layer of appreciation for, and healthy fear of, qualifying speeds at Indianapolis.

The next day, I see the field of 33 brave Turn 1 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway again. Drivers dart from wall to apex to wall at speeds in the 220s, often while navigating traffic or holding off a competitor. Smooth, effortless inputs. All at 167 percent of the steering weight I struggled with in my simulated runs. It is a skill that every driver in the field honed over years of racing whatever they grew up racing, from the closely related Formula 2 racers Théo Pourchaire ran on road courses last year to the completely alien dirt sprint cars that Kyle Larson has run since he was a kid. It is a skill that race winner Josef Newgarden learned on the American open-wheel development ladder that leads to this race, but it is also one that pole sitter Scott McLaughlin picked up in Australian Supercars races at Bathurst and the Gold Coast. It is a skill that borders on the superhuman.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos