Intrigue in the Inbox of an Automotive True-Crime Writer

From the August 2016 issue

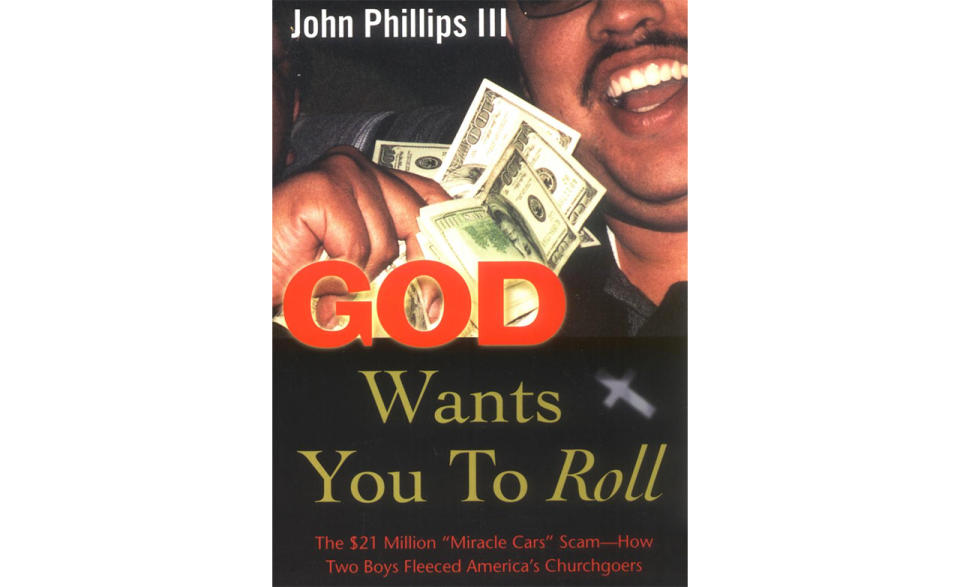

In 2005, I wrote a true-crime book called God Wants You To Roll, the story of two California teens—Robert Gomez and James Nichols—who sold $21 million worth of nonexistent cars to 4000 buyers. The cars typically sold for $1000 or $2000, and some were quite spiffy—a Lamborghini and a couple of Porsches, as I recall. Well, “spiffy” if vehicular ghosts in the heated imaginations of two dead-end security guards are spiffy. They kept the con percolating for five years, then were busted and tried in Kansas City, Missouri. The trial lasted the better part of a month, until the boys both drew 20-plus years in prison. A more entertaining month I have never spent.

Of the two perps, Robert was the more flamboyant. I had lunch with him one day, and he conned a pack of cigarettes from the waitress. He once fielded a phone call from a California detective and, on the spot, began impersonating partner James Nichols, complete with his voice and speech patterns. He played poker with Larry Flynt at Flynt’s Hustler Casino. He once claimed I was his agent and that the two of us were hatching a huge movie deal. He lived in a condo where a scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off had been filmed. And at the time he was arrested in the Hustler Casino, he just happened to be carrying $818,120. It could happen to any of us, right?

Even as he duckwalked off to prison, Robert swore he still had $8.7 million of the loot, stashed prior to the trial. Federal agents told me that was probably correct, and they began searching. Robert alternately told me the money was “in off-shore accounts,” “in Swiss accounts,” “buried in my mom’s backyard,” and “in safekeeping with the Sinaloa cartel in Mexico.” It was all pretty far-fetched, but so was Robert.

And so, 11 years after I last talked to Robert Gomez in a Kansas City jail, I received an anonymous email. In part, it read: “I know where Robert put away millions of dollars' worth of diamonds and real estate throughout Latin America . . . I am willing to reveal where all of this is. Documents, official documentation, and proof of bank boxes.” No name was attached to the message.

That was on March 30. For the next 16 days, we swapped emails. Mr. Anonymous revealed he had “excepted [sic] Jesus Christ” and was “feeling guilty about assisting [Robert] in hiding assets.” He told me he lived in Costa Rica. He said Robert had swapped gold and diamonds for 40 real-estate parcels in Mexico and that he purchased 14 ice-cream shops that he placed in his aunt’s name. Hey, a man’s gotta eat.

I told him that seizing money and real estate from a foreign country would be harder than Chinese Yahtzee and that it would require the assistance and intervention of the feds. Mr. Anonymous didn’t care. He kept encouraging me with tidbits such as, “Robert buried almost six million dollars' worth of gold on one of his family members’ ranch in Guanajuato.” And this: “Robert has some very evil maniac-like friends and business partners. Those maniacs, Mr. Phillips, have long tentacles.” Throughout, he insisted that I say nothing to the cops.

Of course, it was my trial-lawyer father who often told his less savory clients, “If someone says to you, ‘Don’t tell the cops,’ waste no time in telling the cops.” So I began to fret, recalling all the witnesses who’d testified in Missouri who’d had “guilty knowledge” yet continued to aid and abet. Did I have guilty knowledge? I contacted Gary Marshall, a retired federal undercover agent, and Curt Bohling, the assistant U.S. attorney who originally prosecuted the case. To my relief, they urged me to keep communicating but to yell if Mr. Anon started spilling specific actionable details. So far, I wasn’t complicit. But it seemed as if waterboarding might lie in my future.

On the other hand, it struck me as surpassingly strange that the emailer claimed not to have had any contact with Robert for more than 10 years, yet he knew Robert’s inmate number and the location of the latest prison to have welcomed him. And then he added this telling pearl: “Rumors were going around that a large film studio in Mexico City had signed some type of a movie deal with Robert.”

Well, I’d heard a variation of that story before, and this whole emailing routine began issuing the fetid odor of fakery, with Robert as its probable epicenter. My next communication thus read: “Dear Robert: You told me to contact you, so I am.” Very clever on my part, I thought, wondering if some sort of federal commendation was coming my way. But, of course, “Robert” immediately denied that he was Robert and added, “Please stop wasting your time with me.”

At the gym, my friend Heidi advised, “Don’t call Sean Penn just yet.”

Which was terrific advice. So I told the Kansas City feds to stand down, and I emailed Mr. Anon one last time: “Remember Will Rogers’s credo: ‘Never miss a good chance to shut up.’ ” Then I contented myself by binge watching True Detective.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos