Isrun Engelhardt, scholar who probed the truth about the Schäfer prewar expedition to Tibet – obituary

Isrun Engelhardt, who has died aged 80, was a distinguished independent historian of modern Tibet; although she never held a formal academic position, she was a role model for colleagues of all ages, demonstrating the virtues of careful research and generous collaboration.

She is best known for her work on the 1938-39 German expedition to Tibet led by the zoologist Ernst Schäfer (1910-92) which, she argued in a series of publications, was a scientific expedition in intention and execution.

Schäfer had been on two earlier expeditions to eastern Tibet led by the American naturalist Brooke Dolan. In 1933 he joined the Nazi party, and in 1934 he joined Heinrich Himmler’s paramilitary SS, apparently out of personal ambition. Seeking funding for his expedition he met Himmler in person.

Schäfer received no financial sponsorship for the expedition from Himmler but he did receive political support, including German diplomatic requests for the necessary permits from the British authorities. The conditions for this support included a requirement that all five members of the expedition should belong to the SS.

In more recent times, the expedition has been cited as evidence of Nazi fantasies concerning alleged Tibetan links with the Aryan master race. Isrun Engelhardt set herself the task of separating fact from the many fictions.

In her publications on the expedition, based on a careful study of the source materials, Isrun Engelhardt concluded that Schäfer had resisted Himmler’s attempts to impose his own pseudo-scientific agenda, which was based on a racist mythology that members of a “pure” Aryan master race had somehow arrived in the Himalayan region.

She noted, however, that on the eve of the Second World War it was inevitable that a German expedition drawing on diplomatic support from Berlin would risk being caught up in political controversy.

At the same time, she highlighted the expedition’s importance as a source of first-hand information on Tibet at a delicate period in its history. During their six months in Sikkim and two months in Lhasa, the five members of the expedition had taken as many as 20,000 photographs, of which 17,000 negatives survive.

They also collected 2,000 ethnographic objects, but their main focus was on the natural sciences, including biology, ornithology, physical anthropology and magnetic readings.

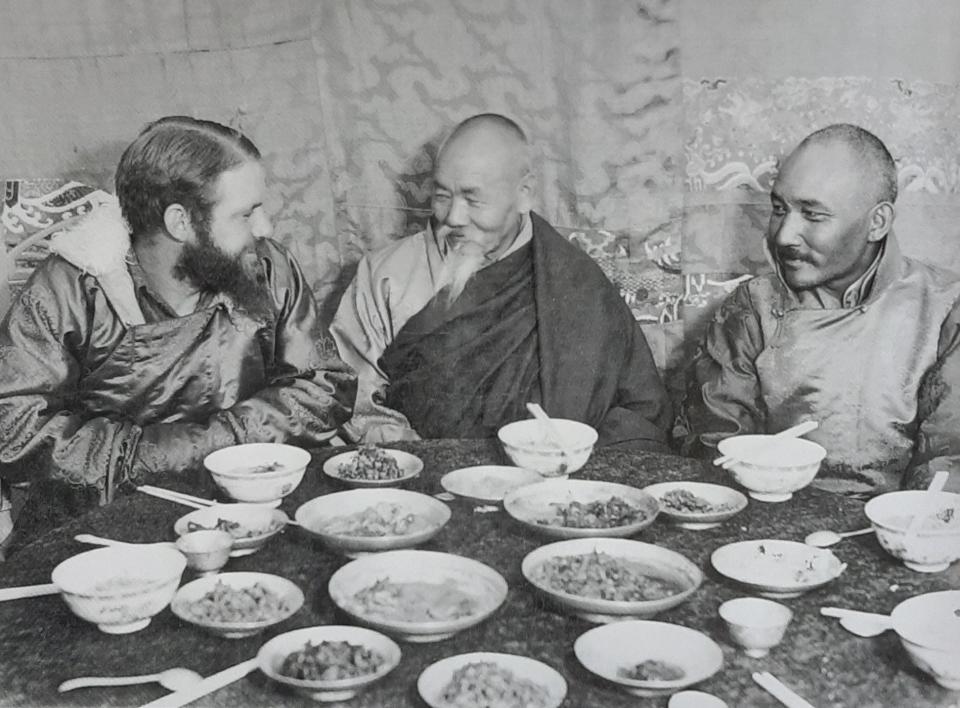

Her edited publication, Tibet in 1938-1939: Photographs from the Ernst Schäfer Expedition to Tibet (2007), is notable both for its analysis and for its detailed photographs of Lhasa society. The expedition members would not have been able to take such photographs, she argued, if they had not enjoyed the support and friendship of their hosts.

She was born Isrun Schwartz into an academic family on September 30 1941 in Arnsdorf, a small village in what was then eastern Germany (now Milków, Poland) in the Riesengebirge mountains. Her family was distantly related to Max Weber, the German sociologist.

Her mother chose the name “Isrun”, which is Icelandic in origin. In view of her later researches, the name had a prophetic quality: it means “the one who knows the secret”. The name is not widely known in Germany and in later years she was occasionally annoyed to receive letters addressed to “Mr Isrun Engelhardt”.

Isrun’s parents had moved to Arnsdorf from Berlin hoping that it would be a place of safety during the Second World War. Those hopes were only partly fulfilled. In the final months of the war their part of Germany was overrun by the Russians.

Her family – which now included three brothers – lived precariously until 1953 when their father, Dr Michael Schwartz, secured a position at the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich. They set up home in the village of Icking to the south of Munich, and Isrun was based there for the rest of her life.

Isrun’s student years were spent in Munich and she met her husband Hans Dietrich Engelhardt at a student residence there; Hans Dietrich later became Professor of Sociology and Social Work at the Munich University of Applied Sciences. Their son Emanuel was born in 1979.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos