The Journalist Who Broke the Biggest Story in Motorsport History

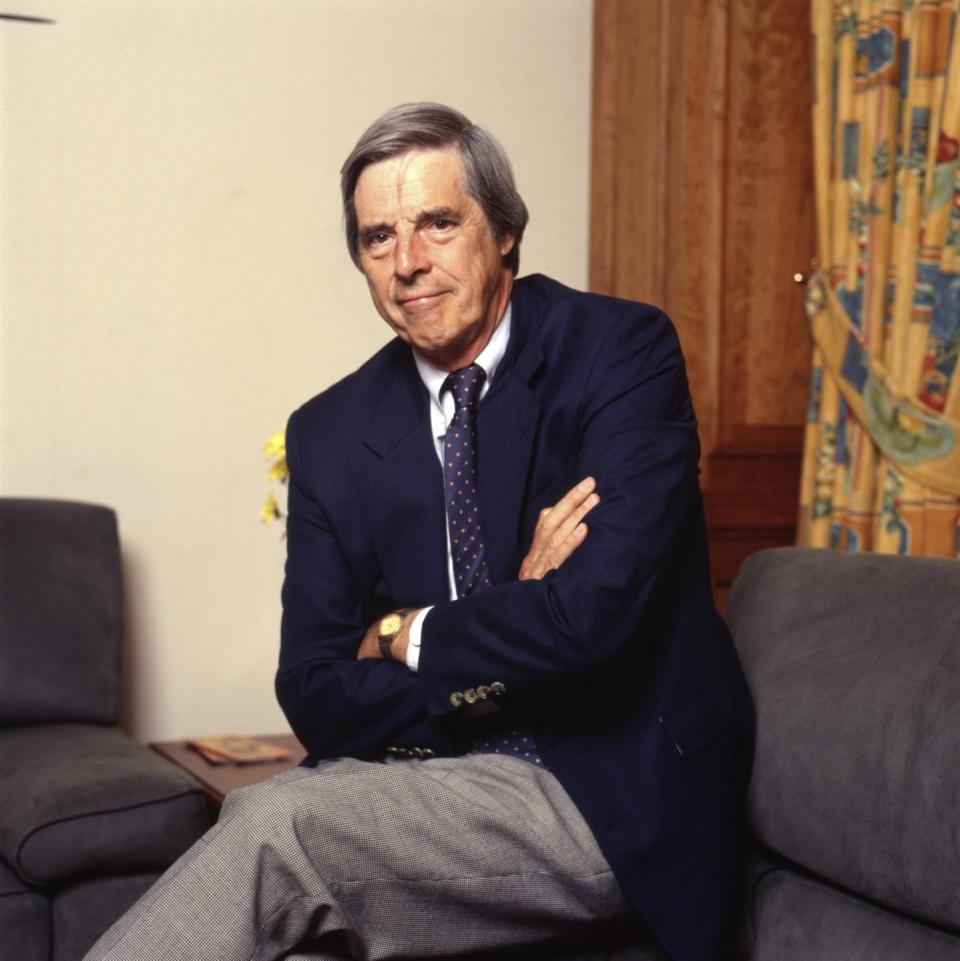

Robert Daley is 91 years old, a highly-successful writer living quietly in Westchester County, New York. He’s written 31 books, many of them best-selling novels. Once the deputy commissioner of the NYPD, he's revered for many things. But for motorsport fans, one thing should stick out. It was Daley who first turned on Americans to what is today the most technologically advanced, richest, and globally popular form of motorsport—Formula 1.

His story starts in 1954, when he went to France as a tourist. He met a French woman on the first day. They married three months after (and still are, 67 years later). At the time, Daley was the publicity director for the New York Giants, and in those days, he could take the off-seasons off. So in 1956, he went to France to visit his in-laws. While he was there, he thought he’d try to sell a couple articles to American newspapers.

“I asked the New York Times if they’d let me cover the 1956 Winter Olympics, in Cortina, Italy,” he says, looking back. “The Times didn’t have the money to send someone from New York. So they said they’d pay me $50 a story, but I had to pay my own way—hotels, travel, everything.” Money was tight, but one could live cheaply in Europe at the time.

At the Cortina Olympics, Daley met the bobsledder and racing driver Alfonso Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, the Marquis de Portago of Spain. If ever a man was a walking emblem of charisma and testosterone, it’s Portago. He was fabulously wealthy, married and famously also dating the Revlon fashion model Linda Christian. “I remember him at the top of the bobsled run at 6am, in between runs,” Daley says. “He talked to me and said the most outrageous things. I knew Portago was a racing driver, and I was fascinated with him.”

Portago talked about racing constantly—a subject Daley knew nothing about. “Every curve has a theoretical limit,” Portago told Daley. “Let’s say a certain curve can be taken at a hundred miles an hour. A great driver like Fangio will take that curve at ninety-nine every single time. I’m not as good as Fangio. I’ll take that curve one time at 97, another time at 98, and a third time at maybe 101. If it take it at 101 I go off the road.”

The following year, when the Giants season ended, Daley and his wife left for Europe again. He was going to try to sell a profile of Portago to a fourth-rate magazine. “I would take anything I could get,” he recalls. Portago was competing for Ferrari in the Mille Miglia, and Daley got an assignment. He filed the story on Friday, May 10, 1957. The next day, Portago crashed his Ferrari in the race. After the accident, as Daley later put it, Portago was found twice. His body had been severed in two.

“My story was killed, and so, I believed, was my writing career,” Daley says. But by this time, he was hooked on Grand Prix racing—the beauty, the danger, the glory. It was a fabulous world that most of America knew nothing about. So he set off in 1958 to introduce the European scene to mainstream America.

Daley’s first F1 race was the 1958 Grand Prix de Monaco. When he wrote his story, he used the term “Crown Prince of auto racing” to describe Stirling Moss, which must have surprised readers of the New York Times, because almost none of them knew who Moss was. Daley had to describe to Americans what the Monaco Grand Prix was, because few readers of the Times would have heard of it. “The race…twists through the streets of Monte Carlo,” he wrote. “The noise is explosive as the cars hurtle through the narrow and at other time sedate streets of the principality.”

All that spring of 1958, Daley moved from Grand Prix to Grand Prix—Zandvoort, the Nurburgring—introducing American readers to F1 and its skilled gladiators. “It was a deadly business and for me as a writer, it was a supreme challenge,” he says. “How do you interest Americans in grand prix racing when they’ve never heard of it before, aren’t a bit interested, and don’t know any of the drivers or cars? How do you make it as fascinating to read about, as it appeared to my eyes in person?”

Daley found a Trojan horse in the Californian Phil Hill, who that very season became the first American to break into the ranks of Ferrari drivers. “Phil was never that warm of a guy but I spent a hell of a lot of time with him and I deeply cared for him,” Daley remembers. “I always said if anything ever happened to Phil I’d never go to a race again. He was the one who gave me all the information. I realized as a journalist…. You need one informant to take you inside. The same thing is true in detective work.”

That spring, Hill brought Daley through the threshold of Enzo Ferrari’s office, so that Daley could write the first profile ever to appear in the mainstream American press of Ferrari, the man. Daley remembers feeling awed by this riddle of a man who made cars that cost $15,000—an unheard of fortune. Daley had learned enough about European racing to know that Ferrari drivers perished with surprising regularity; two of them (Luigi Musso and Peter Collins) would be killed that very F1 season. Daley remembers seeing photos on the wall of these dead drivers, in Ferrari’s office. One of them was the Marquis de Portago.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos