Katherine Legge's Indy 500 Wasn't The Redemption She Wanted, But She May Have Changed Racing Forever

Practice for the 2024 Indianapolis 500 had yet to start when I first spoke to Katherine Legge about her fourth attempt at competing in the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. In 2023, Legge was the first retirement in the event. When I asked why she wanted to come back in 2024, her answer was simple: Redemption.

“I didn’t want to go out like that,” Legge said, referring to a mistake during her first pit stop that led her to ultimately retire from the event. “I want people to remember me for what I’m actually capable of rather than the disaster of last year’s race.”

Despite admitting that she still felt like a “rookie” thanks to 2023's early exit, Legge was optimistic. Her No. 51 Dale Coyne Racing Honda would be emblazoned with an e.l.f. Cosmetics partnership — a partnership that soon expanded to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the 108th running of the Indy 500. According to Legge, she “wanted to see what she could achieve” with such an “iconic brand.”

On the track, unfortunately, there was little achievement to be found. The engine in her race car failed on the 23rd lap. Legge was one of three Honda drivers to retire from the race in a puff of disappointing smoke. She was scored in 29th place.

And yet Katherine Legge still has so much to be proud of in 2024. She found some redemption; it just wasn’t on the race track. It came in the form of her sponsorship with e.l.f. Cosmetics.

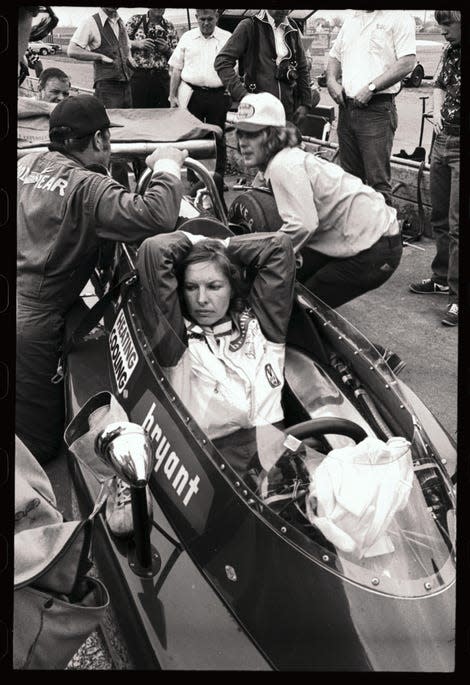

In 1977, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway could very well have been the Annapurna Mountain for Janet Guthrie.

Yes, she had already completed the first step of racing in Indianapolis the year before: She had entered. She had completed rookie orientation. She had practiced. She had forced the denizens of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to accept a woman in their midst, knowing full well that it had taken a court case five years before to finally allow some women the opportunity to be allowed in the pit lane and garage area. It was still a shock to see a woman driving, and when Guthrie’s car succumbed to a slew of mechanical gremlins before she had a chance to qualify, it seemingly proved to her doubters that women truly shouldn’t compete in the Indy 500. When she arrived in 1977, she wasn’t just representing her own driving skills; she was representing all women everywhere.

It’s easy to see Guthrie’s accomplishment as a personal one, but it’s just as easy to map her success onto all women. When Janet Guthrie qualified for the 1977 Indianapolis 500, she proved that she was capable of the feat, yes. She also proved that, with the right experience and the right backing, any woman could take on the challenge of the Speedway. But what we tend to forget is that, in her barrier-breaking year, Guthrie finished in 29th after a broken timing gear ended her day on lap 27.

Why? Because the box score result matters far less than the cultural impact. Janet Guthrie had overcome the odds. She had ignored heckling from fans asking her to show them their chest. She had battled a massive amount of negative press that questioned her abilities, as if she hadn’t been racing for over a decade by the time she first tried her hand at Indy. She had heard her competitors speak poorly about her skill. And with a functioning car at her disposal, she was able to silence the criticism — at least for a while. Janet Guthrie had proved that women can race Indy cars, too.

The 108th running of the Indianapolis 500 was Katherine Legge’s fourth-ever shot at the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. The now-43-year-old British driver had her first two attempts in 2012 and 2013, with Dragon Racing and Schmidt Peterson Motorsports, respectively. After that came a decade-long break where Legge found success in the sports car realm — but open-wheel racing remained Legge’s first love.

“I was a very lucky young lady in that I found something that I was passionate about at a young age and that was go-karting,” Legge told Jalopnik back in 2022. “I had parents that supported it — especially my dad. “I was daddy’s little girl. I was an adrenaline junkie. We would travel all around Europe and go to different race tracks. And it was fun, but it also gave me a focus, a passion, and a purpose.”

Legge honed her craft in the karting world for nearly a decade before moving up the open-wheel ladder through Formula Three, Formula Renault and Formula Ford. She was the first woman to win the “Rising Star” award from the British Racing Drivers Club — a feat she earned by besting Kimi Raikkonen’s lap record in a Zetec race. Then, in 2004, she showed up at Cosworth’s UK office, refusing to leave until she met with boss Kevin Kalkhoven. Her persistence and drive impressed a man who had initially intended to shoo her from the premises; instead, she was offered a chance to prove herself in America’s Toyota Atlantic Championship.

Legge’s open-wheel opportunities soon morphed into seats in sports cars after a few years in Champ Car and IndyCar; she drove the inimitable three-wheeled DeltaWing before securing her first GTD class victory with Mike Shank Racing in 2017.

But her shot at the 2024 Indianapolis 500 looked to be her best one yet thanks to e.l.f. Cosmetics. The makeup and skincare brand first teamed up with Legge in 2023 before opting to expand its partnership with her in 2024. Rather than being a minor sponsor, e.l.f. became Legge’s primary partner, with its pink-and-black branding adorning her Dale Coyne Honda. The company then expanded its sponsorship to include the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as a whole, as well as the 108th Indy 500.

Capping off the affair was a groundbreaking e.l.f. activation in IMS’ infield. There, a woman DJ performed all day long while fans of all sorts could earn free products (ranging from some much-needed sunscreen to bright red lip-plumping gloss), undergo a quick makeover, learn about the history of women in the Indy 500, and take home some exclusive e.l.f./Legge swag, including scarves, hats, and magnets.

It was an activation unlike anything I’ve seen at a race track before. I’ve attended races around the world, and it’s extremely rare to find anything designed to appeal to women. I’ve seen a few merch tents, and I’ve heard of events like Le Mans putting together some specific zones where the male race fans could leave their wives. I had never seen a sponsor turn out so profoundly, and I certainly never expected a makeup brand to offer the coolest and most welcoming stand at the Indianapolis 500. Young girls posed with Katherine Legge’s displayed driving suit. Little boys went wild for the e.l.f./Legge hats. Adult women asked professional makeup artists to show them how to use blush and highlighter. Grown men asked if they could swap their free lip balm sample for something more exciting, because they had a young girl at home who was experimenting with makeup for the first time.

It’s difficult to quantify exactly how important that activation will be in the future of motorsport, but to me, it felt huge. The e.l.f. activation represented a seismic shift in the motorsport world, in how we can not just appeal to female fans, but draw them into the sport in an authentic way. If I’m entirely honest, it felt like the start of a female-forward racing revolution.

When Katherine Legge finished her interview after retiring from the race, she thanked the crowd and waved. Countless people — men and women alike — rose to their feet to applaud her, because this year, it was less about her performance. Instead, it was about the impact that she and her primary sponsor made on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

In 1978, Janet Guthrie took another stab at the Indianapolis 500. She arrived at the Speedway disguising a broken wrist in order to try her luck with a Wildcat chassis outfitted with a DGS, a last-ditch effort at keeping the elderly Offenhauser engines competitive. She qualified a stunning 15th, outranking legends like Bobby Unser and A. J. Foyt. Guthrie and her broken wrist held on until the checkered flag fell. She had finished ninth — the best finish for a woman at the Indy 500 until Danica Patrick’s fourth place in 2005.

That ninth-place finish hasn’t quite permeated our memories in the same way as Guthrie’s first attempt at the 500, because by 1978, Guthrie had already made a huge impact on the American motorsport zeitgeist. The very fact that Guthrie qualified for one of the most challenging races in the world meant she’d made a mark that even a personal success like a top 10 couldn’t rewrite. She had already forced culture to change.

When we look back on Katherine Legge’s 2024 Indy 500, I don’t think the result will matter quite as much as her impact. Legge brought e.l.f. Cosmetics to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and the brand used its leverage to carve out a comfortable, well-thought-out space for women in the midst of a male-dominated world. Her ultimate finishing position surely won’t be the personal result she wanted, but she can — and should — be proud of the change she brought to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

And who knows — maybe next year, Legge will do her best Janet Guthrie impression and cap off her cultural impact with a career-best finish. If anyone can do it, it’s Katherine Legge.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos