Lightning Lap 2012: Ultimate Performance Test v6.0

From the February 2012 issue of Car and Driver.

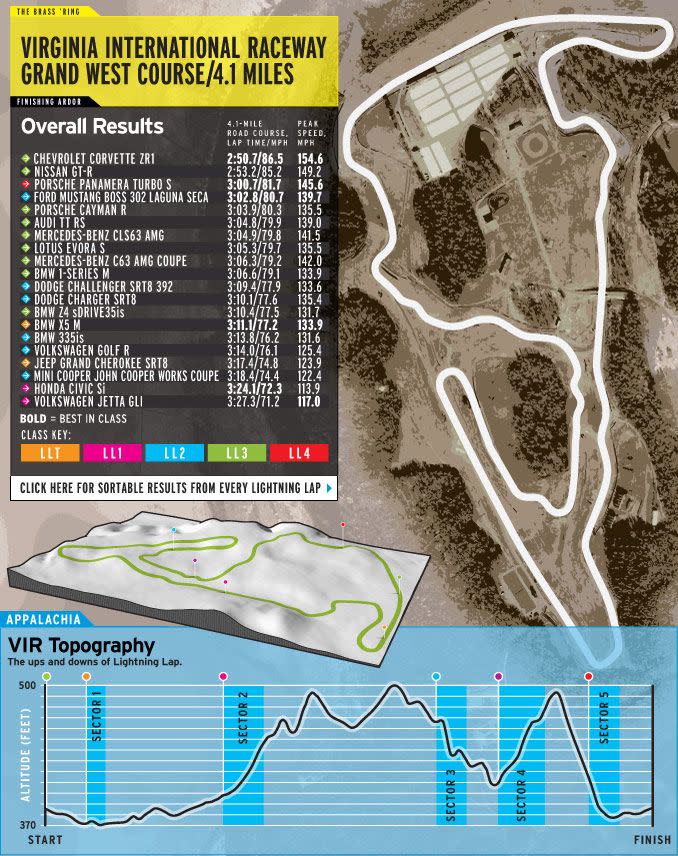

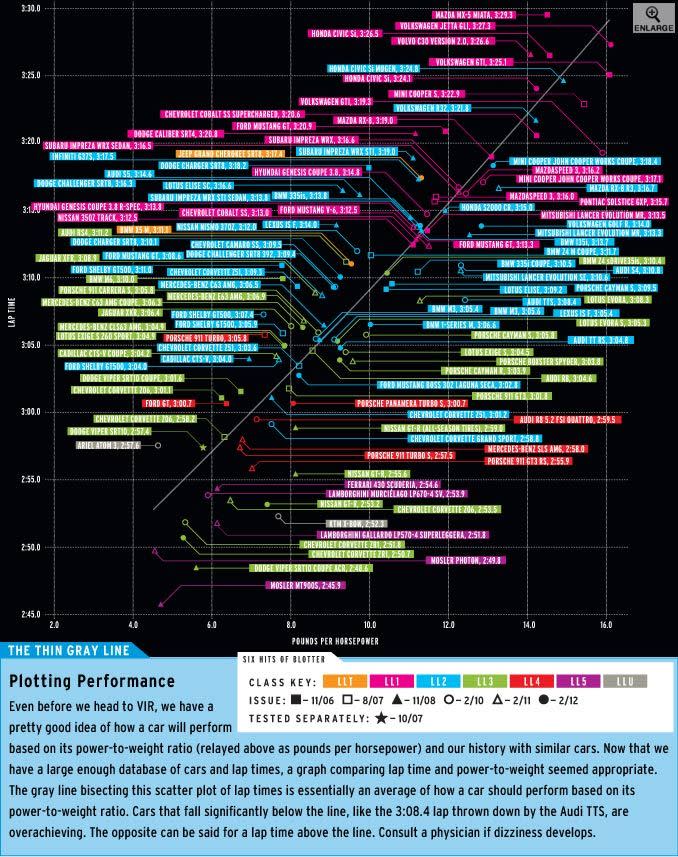

Within a stone’s throw of the invisible line that separates North Carolina from Virginia is a very visible 4.1-mile winding line known as Virginia International Raceway’s (VIR) Grand West Course. Over the past six years, and in as many installments, we have brought production cars (115 of them, including this year’s crop) here in an effort to find just how quick the sportiest cars on the market are in a controlled environment.

Lightning Lap is our home-brewed version of the Nürburgring Nordschleife test that numerous manufacturers do when tuning new automobiles. Even though VIR is less than a third the length of the ’Ring, its long straights, elevation changes, and combination of slow, fast, and, scary-fast corners test a car’s capabilities better than any other track in North America.

To complete a lap in less than three minutes (think of it as VIR’s version of the ’Ring’s eight-minute mark), a production car must have unflappable brakes, high levels of grip, sure-footed handling, and, with two 0.6-mile-long straights, a stout engine.

For this test, the ultimate performance crucible, we don’t factor in how ridiculous a car looks, or how ugly it sounds, or any other subjective criteria. We rank the vehicles based only on best lap time.

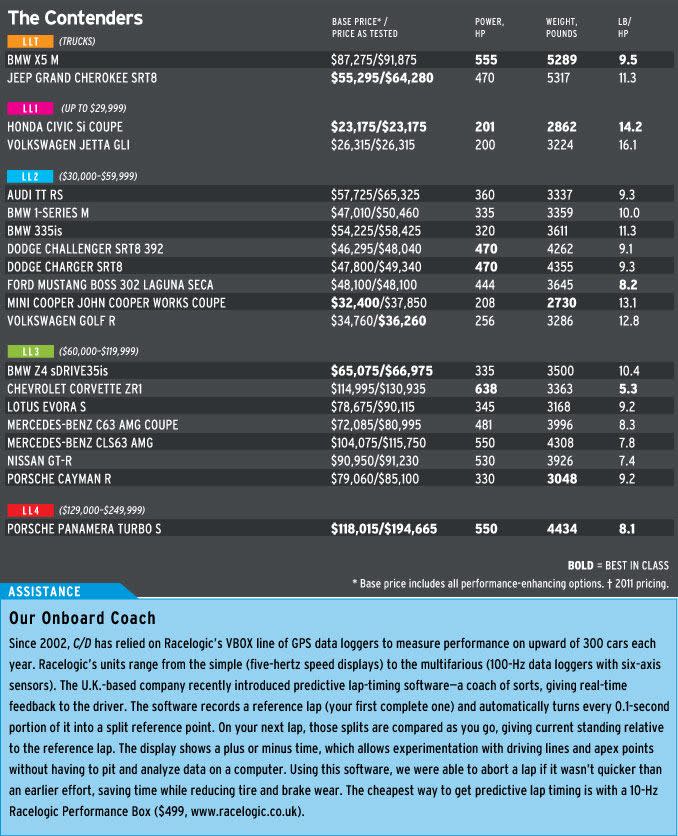

Each car is slotted into one of the following five classes according to its base price, which includes all performance-enhancing options.

There are no LL5 cars ($250,000 and above) this year, and we did not invite any non-production LLU cars (“U” for “unclassified”). But we did bring a pair of high-po sport-utility vehicles, so we created a new class for SUVs and trucks called LLT.

The Rules

The cars featured here are all unmodified production vehicles. We requested that each model be fitted with the sportiest options, such as bigger brakes, summer tires, sport suspensions, and racing stripes, the latter so we’d feel cooler. We start the test with a full tank of fuel, which is also when we weigh each car. Tire pressures are set each morning to the manufacturers’ cold-inflation recommendations. Lap times and sector data are collected with GPS-based Racelogic VBOXs using predictive lap timing. All the cars are driven hard multiple times and by multiple drivers to ensure we extract the absolute best lap from each.

As it turns out, with lightning comes rain. Lots of it. Two of our three scheduled days at VIR were rain soaked. Running in the wet is great for developing car-control skills, not for setting lap times, which meant we had to be on our game when the sky finally cleared.

Can one of our two 5300-pound SUVs knock the Mosler MT900S from its 2:45.9 perch? Well, no. But one of them blew us away. The other we wrinkled in the slowest, wettest, least dramatic tire-wall contact in the known universe. This year marks the return of the 638-hp monster that answers to “ZR1.” For LL No. 6, it shows up wearing gummy shoes and its best shot at smacking down the Mosler. And Ford’s Mustang Boss 302 Laguna Seca makes an attempt at a stunning performance-to-dollar achievement: a sub-three-minute lap for less than $50,000. Can it do it? Will it blow up trying? And what creative excuses will our drivers come up with if it doesn’t? Read on to find out.

And don’t forget to spend some time number-spelunking in the three pages of on-track data.

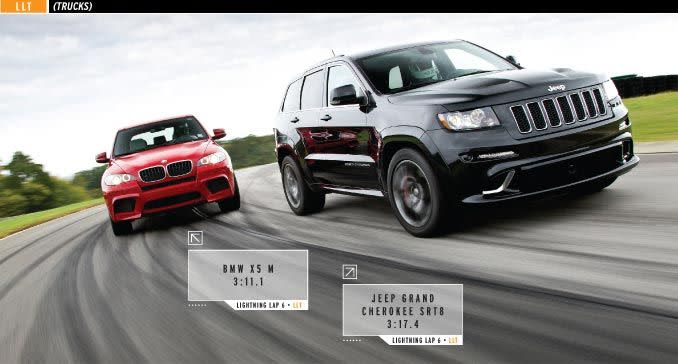

LLT (Trucks)

Jeep Grand Cherokee SRT8 – LLT, 3:17.4

Remember when Jesse “The Body” Ventura left wrestling to pursue a political career? The Grand Cherokee’s transformation from luxury SUV into 5317-pound, SRT-tuned track weapon is just as unlikely and arguably as successful. It’s the heaviest vehicle we’ve run at VIR, but its benign manners allowed it to achieve a 3:17.4 lap time, almost identical to the performance we put down in an Infiniti G37S a few years ago. The high seating position feels so wrong, but the Jeep’s tight roll control and unperturbed suspension feel so right. It has better body discipline than the Charger SRT8 we drove right after.

The Cherokee SRT8 is a tame beast. It turns in securely, although it never lets you forget that you’re trying to make two-and-a-half tons change direction. That said, in the uphill esses of sector two [see track map], the Cherokee felt dead stable entering at 109.2 mph (roughly the same speed as the Audi TTS from 2010). Grip from the wide Pirelli P Zeros goes away gradually, and the SRT8 is surprisingly neutral. Nothing upsets this rig. It sops up the curbing of the uphill esses with what feels like endless wheel travel. Turn into the nearly 90-mph downhill off-camber left-hander at the exit of that section, and there’s admirable grip and only a hint of understeer. It leaves you thinking, “I can do that quicker,” until you find yourself sliding through the grass like a giant croquet ball.

Aerodynamics and weight conspire to limit the Cherokee to an unimpressive 123.9 mph on the front straight. That relatively low speed allows for later braking, and the stoppers seem happy to comply. Velocity disappears quickly, and pedal feel remains consistent. The engine pulls so hard into the rev limiter that we found ourselves worrying about upshifting in time.

Like Jesse Ventura, the Cherokee has found success in the unlikeliest place.

BMW X5 M – LLT, 3:11.1

Despite the X5 M’s flabby, 5289-pound curb weight, we expected it to be fast. And it is. Forget about the Grand Cherokee SRT8. The BMW blows its doors off. This SUV is quicker around VIR than the BMW 335is, as well as the Audi RS4 and BMW Z4 M coupe we ran here in 2007. Hell, it hangs off the rear bumper of the Mitsubishi Lancer Evo.

We also expected that the brakes would perform well, and they exceeded in that regard by shrugging off a five-lap stint.

But we didn’t see this one coming: The X5 M’s plentiful ground clearance benefitted its lap time. Exiting the “Bitch” corner a little wide, we dropped a tire off track, which did not faze the X5 M’s chassis even a bit. The four-wheel drive did its job and the left-rear Bridgestone Dueler kicked up some grass, so we carried on with what ended up being the X5 M’s fastest lap of 3:11.1.

This was not exactly your typical hot lap, even without the agricultural excursion. Like the Jeep, or just about any other SUV one is bold enough to take onto a track, the X5 M feels clumsy at first. The lofty seating position, which feels about as high as the roof of the Cayman R, exaggerates pitch and roll. Thankfully the BMW’s seats are better than most cars’, with beefy bolsters to keep the driver well planted. Once acclimated to the X5 M’s peculiarities, entering the uphill esses at 113.1 mph feels fairly normal, as does blasting down the front straight at 133.9 mph.

The X5 M impressed us with a sports sedan’s appetite for corners. Wide Duelers (315s in back) grip the track through sector one at 0.90 g with an abundance of understeer. With a little throttle, we could erase the push. And with a more liberal application of power, the tires will break loose for some righteous opposite-lock entertainment. We didn’t really see that one coming, either.

LL1 (Up to $29,999)

Volkswagen Jetta GLI – LL1, 3:27.3

How much difference does one letter make? At VIR, it apparently counts for eight seconds. That’s how much slower the Jetta GLI is than its hot-hatch counterpart, the GTI. The GLI is not a GTI despite an identical powertrain and a curb weight only 46 pounds heftier. The most obvious difference, in terms of performance potential, is that the GLI rides on all-season tires whereas the GTI we ran two years ago sported summer rubber. The difference in grip—0.81 g versus 0.85 g through sector one—limits the car all over the track.

To make matters worse, there’s no way to disable the GLI’s stability-control system. You can’t even turn off the traction control portion, something you can do in the GTI. So we fought the car for control of, well, the car. Try to take a corner at the limit, and the stability control jumps in, reining in your speed and sending a disconcerting twitch through the steering wheel. This near-constant intervention also taxes the brakes, which heat up and lose performance in as little as a single lap.

A fast lap in the GLI requires finesse. We had to tread lightly to avoid interference from the stability-control system. That’s a shame, too, because we believe the GLI has predictable handling and a decent chassis under the electronic nannies. The GLI posted the second-slowest lap in the six Lightning Lap events we’ve run so far, beating the Mazda MX-5 Miata from our inaugural event by two seconds. Guess which one we’d rather drive.

Honda Civic Si – LL1, 3:24.1

The new Civic Si’s performance on the racetrack was, perhaps predictably, limited by the things that make it an easy-to-live-with sporty coupe. As expected, the 2.4-liter four sings, the shifter is a joy to push through the gates, and the pedals are positioned well for heel-and-toe downshifts. But the Civic had this year’s slowest peak speed at 113.9 mph, 3.1 mph slower than the Jetta GLI’s (which has the worst power-to-weight ratio here). And the Civic requires frequent shifting to keep the engine near its power peak (201 horsepower at 7000 rpm). Also, the upper-dash shift lights aren’t much help, as they only illuminate for the last few hundred revs and require too much attention to properly monitor.

From a handling standpoint, the Si’s chassis feels able but is let down by tires that have barely more than one lap of maximum performance to offer. With the second-lightest curb weight in this year’s test and a supremely composed suspension, the Si manages the winding sector four faster than either the BMW 335is or the Mini. This new hot Civic posts a lap 2.4 seconds quicker than the old Si. It’s even 0.7 second quicker than the Mugen-tuned version we tested a few years ago. Nevertheless, like most of the more affordable cars at Lightning Lap, the Civic Si is more of a sporty variant of a daily driver than a true sports coupe. This is particularly evident in the seat, which left us hanging on to the steering wheel for lateral support. The chassis and powertrain are sweet, but if we were to venture back out on the racecourse in the Civic, we’d wish for more power and more-aggressive tires.

LL2 ($30,000–$59,999)

Mini Cooper John Cooper Works Coupe – LL2, 3:18.4

Think the Mini Coupe would be faster than its hatchback sibling? It isn’t. In fact, this particular Coupe is 1.3 seconds slower than the hatchback Mini Cooper John Cooper Works we ran a couple of years ago. Despite the overall deficit, the Coupe boasts a slightly higher peak speed on the main straight and averages 4.8 mph faster through the climbing esses. And remember that the 208-hp engine and gearing of the six-speed manual are the same across all Mini JCW models. So the difference could be due to an extra 56 pounds of curb weight or a less grippy track freshly dried from a thunderstorm.

Aside from the silly chapeau roof and two fewer seats, everything in the Coupe is familiarly Mini. The steering is hyper-reactive, bordering on twitchy until the tires warm up. Get on the throttle too soon when exiting a corner, and the inside front tire lights up and the front end pushes wide. Get off the brakes too late after turning in, and the back end threatens to slide. Get used to the quick reactions, though, and the Mini starts to inspire confidence on the track. The stiff ride, beyond unpleasant in street driving, lends itself to flat cornering. And the brakes hold up well to abuse.

In the two years since the previous John Cooper Works participated, window-sticker inflation has pushed the Mini (the Coupe carries a $1300 premium) into the LL2 bracket, a segment as ruthless as Stalin after a bad mustache trim. But lap times and price aside, the Coupe is just as much fun to wring out as the hatchback.

Volkswagen Golf R – LL2, 3:14.0

The Volkswagen faithful might not think of their beloved, premium, all-wheel-drive R models as direct competitors for putative rally cars such as the Subaru WRX STI and the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution. But pricing and driveline-configuration similarities make such comparisons irresistible. In terms of lap times, the 2008 R32 (VW’s erstwhile prodigal son) didn’t hold up well to the Japanese. We recorded a 3:21.8 lap for the R32 in 2008, which is a long way off the times set last year by the WRX STI (3:13.8) and the Evolution SE (3:10.6). And the GTI, as good as it might be, hasn’t been able to keep up with the rally replicas.

Compared with the old R32, the new R is quicker through all sectors and, at 125.4 mph, is faster down the front straight by 9.2 mph. At 3:14.0, it also posted a 7.8-second-quicker lap time than its predecessor, despite the modest 6-hp advantage its turbocharged four has over the old six-cylinder R32. That lap is just off the STI’s and a meaningful 9.2 seconds faster than what a GTI recorded in 2010. The new car is, however, 269 pounds lighter.

The R’s performance results are basically midpack at every split compared with its LL2 peers, but they are nonetheless impressive. Its brakes offer good, fade-free response and modulation, on par with the class-leading Evo’s. The steering wheel is fairly light in its weighting and transmits plenty of information for the driver to make sensible choices about how much angle to dial in. And, as with the GTI, the Golf R remains stable through the uphill esses as high-speed curb bumps barely affect its chassis.

The Golf R nails all the subjective criteria that combine to make a great-driving car. And who knows. If some of the brand’s World Rally Championship know-how—a new venture with a car based on the Euro-market Polo—trickles into the next-generation R, Volkswagen might win in the objective ranking, too.

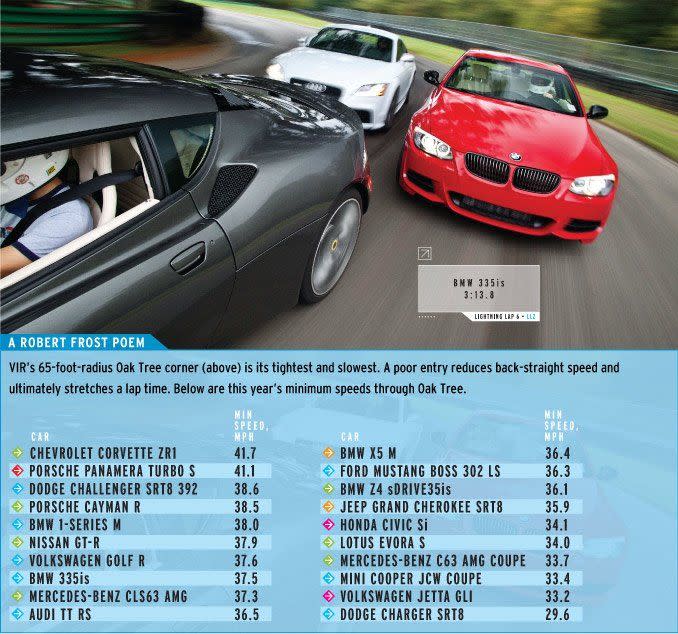

BMW 335is – LL2, 3:13.8

The 3:10.5 lap a 335i turned at our 2007 VIR event is just another reason to believe that those early turbocharged BMWs made more power than the advertised 300 ponies. After all, the 320-hp 335is is only 0.1 mph faster down the front straight, at 131.6 mph.

Even with the slower-than-expected lap time, the 335is is so committed to chassis neutrality that it might as well be Swiss. From the sharp left-hand Turn Four until the start of sector two, the 335is will change direction as readily with the gas pedal as with the steering wheel.

Our 335is test car was equipped withthe optional seven-speed dual-clutch automatic that is also offered in the M3. This gearbox has proven more problematic for track work than the aforementioned 335i’s traditional manual. The transmission did not resist shifting when the 335is was side-loaded, as it did in the Z4 we ran this year, but the gear display is tiny and is nestled between the gauges, requiring more than a quick glance to ascertain which gear is engaged. And the steering-wheel paddles sometimes did not follow through on a command.

A transmission can’t be the only culprit for a car’s disappointing performance, right? Actually, it was the only complaint of the two drivers who drove the 335is. Subjectively, there were no glaring criticisms. Its chassis is slightly more upset by curbing, and the steering turn-in isn’t as immediate as the 1-series M’s. But the brake pedal offers nice initial bite; it’s easy to modulate and thus trail-brake.

The 335is is a joy to drive, even if this one was simply not as quick as the 335i from several years ago. We would choose the standard manual transmission if it were our money. And maybe that would improve the BMW’s lap time. It would certainly increase the fun quotient.

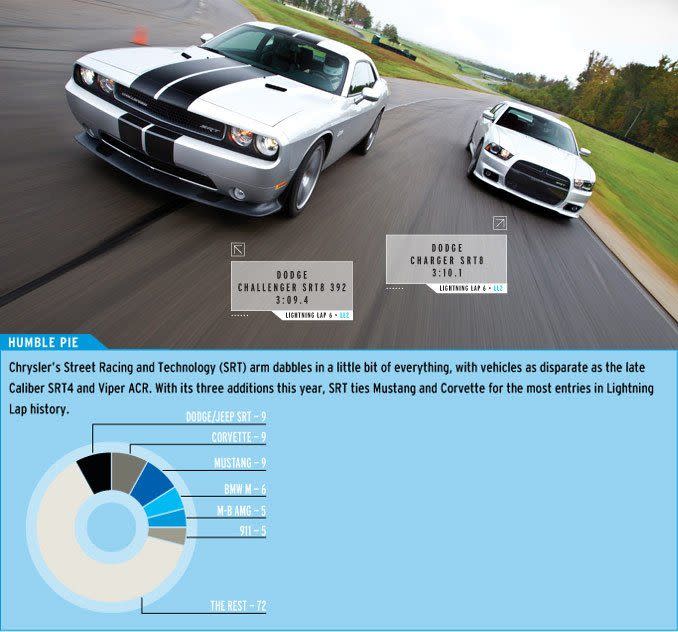

Dodge Charger SRT8 – LL2, 3:10.1

Forget the old Charger SRT8, which inexplicably showed up at our inaugural Lightning Lap in 2006 wearing all-season tires. The new car, sporting Goodyear Eagle F1 Supercar rubber and 45 more horsepower, is a vastly different machine. Well, mostly it is. The Charger is still a huge car, and its bigness is ever present, but it moves with an unexpected grace and fluidity. There is an initial softness to roll control, more than in the Grand Cherokee SRT8, but the Charger is remarkably stable though the esses. It’s the equivalent of the dancing hippos in Fantasia. And it’s a hippo that chops 8.1 seconds per lap off the old car’s performance.

Like Dodge’s Challenger, the Charger has extraordinary brakes and a pedal that never went soft on us. The Charger feels much like its coupe sibling but with a tall-geared automatic transmission and a greater propensity to oversteer. These two attributes conspire at the slow Oak Tree bend where, after scrubbing down to 29.6 mph and shifting into first, we had to wait and wait to get back on the power. The long ratios mean the Charger takes a number of fast corners in third where others cars are in fourth.

The primary flaw here, predictably, is the automatic transmission. Choosing gears via the steering-wheel paddles works better than the mysterious shifting logic of the fully automatic setting, but because the engine pulls to redline so readily, it’s easy to get caught by the slow response to manual commands. For a car that is unlikely to see much track use from its owners, though,

the Charger SRT8 does a credible impression of a two-ton ballerina.

Dodge Challenger SRT8 392 – LL2, 3:09.4

The last time the Challenger SRT8 circled VIR, we wrote that it felt big and miserable as it turned a 3:16.3 lap. Enter the new Challenger SRT8, which lopped off 6.9 seconds from the 2008 model’s time, beating the now-discontinued BMW M6 (3:10.0) we ran here in 2006.

So, how’d it do that? For 2011, the Challenger received new dampers and extensive suspension-geometry changes, including negative camber settings at all four corners. Even with the same Goodyear F1 Supercar tires, the Challenger now slices into corners as if it has lost a thousand pounds. Light steering now communicates cornering loads and front-tire slip with predictable, rising effort. There’s more grip, a daringly neutral balance, and a deftness that was missing before. In the first corner off the straight, the Challenger held on at 0.91 g compared with the 0.85 g of the ’08 model; it also exited at 69.7 mph, 7.2 mph faster than before.

A little initial compliance remains in the chassis, and you can feel the huge body moving on its springs. But once the Challenger takes a set, it feels connected. Braking has a similar effect as the Challenger dives onto its nose during hard braking, which makes corner setup feel a bit sloppy. The dive isn’t unstable, just a little ugly. Pedal effort and travel increase as the brakes get hot, but excellent stopping power remains.

An additional 45 horsepower and 50 extra pound-feet of torque from the 365-cc-larger, 6.4-liter V-8 net a 4.2-mph improvement on the front straight. The Tremec 6060 six-speed manual wasted some time due to its unwillingness to accept second-gear downshifts; it’s also easy to beat the third-gear synchros on upshifts. Another gripe: outward visibility. Tiny windowsand a hood that reaches all the way to the 1970s conspire against the light-on-its-feet chassis to make this car feel big. There’s no getting around the Challenger’s girth, but at VIR, it has traded misery for something approaching mastery.

BMW 1-series M – LL2, 3:06.6

If there is anyone left out there unconvinced of the benefits of a wide torque band, they should take a lap in a 1-series M. At VIR, the 1M uses third gear for roughly 80 percent of the track because its 370 pound-feet of torque are available as low as 1500 rpm. That torque and fairly tall gearing (111 mph max in third gear) meant that we could go through sector four without a potentially chassis-upsetting gearchange. That helped the 1M complete that section in 14.7 seconds, tieing the mid-engined Cayman R and Evora S.

The same can be said for sector five, where we sailed along in the 1M, locked in third. In most other cars, we had to perform a fourth-to-third downshift there. With a short wheelbase and M3 suspension components, wheels, and tires, the 1M turns in crisply, without delay, and remains gleefully free of understeer. When we hopped back onto the torque wave exiting a corner, we were greeted with a healthy but manageable dose of oversteer. This was common but most pronounced at slow corners, such as Turn One and Oak Tree. Most of sector four is performed on the ragged edge of a full-on high-speed D1-like drift.

Lap after lap, the 1M’s brakes erased speed without a fight or any fade. And since it topped out at 133.9 mph on the front straight, there was a lot of speed to erase.

Even if the 1M couldn’t top the 3:05.4 lap its big brother the M3 posted in 2010, it delivers real M performance. And, like a bona fide sports car, it demands respect.

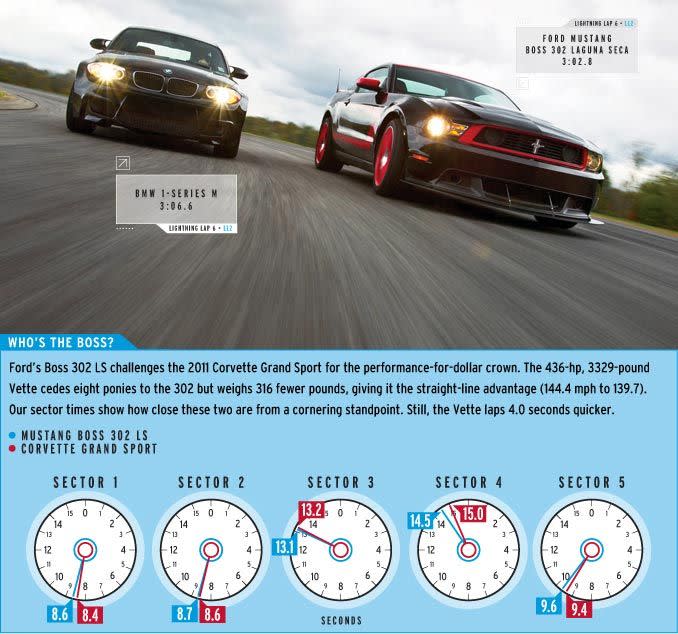

Ford Mustang Boss 302 Laguna Seca – LL2, 3:02.8

Forget the numbers for a moment. The Boss 302 Laguna Seca (the raciest of racy factory Mustangs) fires so many of the right neurons that it could be the one car we’d drive forever. Ford excelled by focusing on the full high-performance experience, not just this 444-hp Mustang’s acceleration or lap times. Sometimes the feel, the sounds, and, yes, the smells can overshadow what a car achieves on the track.

At this point, you might be suspecting that we’re trying to cover up lackluster lap times with all this fuzzy talk of feel. We are not. The Boss is the quickest Mustang we’ve ever run at VIR. Forget the GT—this car posted a lap time 1.2 seconds quicker than last year’s 550-hp Shelby GT500. Only a Corvette Grand Sport beats the Boss on a speed/dollar metric.

But the Corvette doesn’t have the Mustang’s side-exhaust outlets that blast their rumble right under your ears. In our notebook, we scribbled: “God’s own engine roar.” Electric power steering doesn’t dull the Boss’s road feel. The cue-ball shifter is just about perfect. And the stitching on the seats looks fantastic.

If we were looking for faults, we’d say that the rear end has too much grip (the Laguna Seca model wears 10-inch-wide rear wheels, 0.5 inch wider than the regular Boss 302’s). That huge front splitter is there to increase front-end traction, but it’s not enough. The upside is that the rear never threatens to snap around. The Boss is a kitten to drive, though it sounds like a tiger. We lapped it until the tank ran dry.

Audi TT RS – LL2, 3:04.8

Is this TT RS the ultimate version of the VW Golf architecture? Or is it more like one-third of a Bugatti Veyron? This question popped into our heads after the TT RS hit 139.0 mph on the front straight, its five-cylinder wailing like a 1980s Quattro rally car.

The TT RS is easier to drive than any 360-hp car we’ve ever experienced on a racetrack. And it put down a time only 0.2 second shy of Audi’s own V-8–powered R8. It makes you think you’re good enough to change your last name to Mikkola. Here’s what it takes: Brake hard (pedal feel is firm, and the brakes grab), turn in (steering is heavy, but the front end darts into a corner eagerly), and simply put down the power early and let the all-wheel drive sort it out. In sector one, the TT RS achieved the same peak grip as the Porsche Cayman R, but the TT RS put its power down earlier, leading to a quicker sector time and a higher exit speed. At the limit, there’s a hint of understeer, a familiar enough safety net. Lift slightly, and the front tires regain grip. Slides happen in slow motion and are easy to catch. One corner worker commented that the TT RS looked like it was sucked down onto the track as it alternated between understeer and neutrality in the off-camber corners of sector four.

This Audi is graced with steering that weights up in response to the stress of the front tires in a way that reminds us of the Cayman R. The suspension shrugs off curbing, and the planted feel and accurate steering support a 120.1-mph entry into the uphill esses—quicker than the Exige S 260 Sport.

Shifting the six-speed manual, we probably lost a couple of ticks to a TT RS equipped with the not-for-the-U.S. dual-clutch automatic from the TTS. But working the light-effort six-speed is a lot more fun.

The greatest Golf or a slice of Bugatti? Yes and yes.

LL3 ($60,000–$119,999)

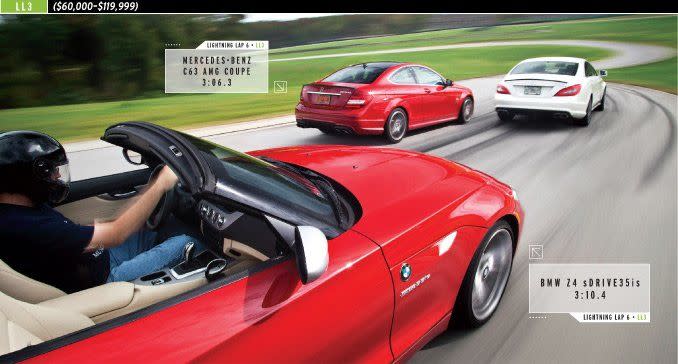

BMW Z4 sDrive35is – LL3, 3:10.4

Whistling toward the end of VIR’s 2979-foot back straight at about 125 mph, we jumped on the brakes at a point we deemed plenty early. After lapping the track in several other cars, we had a pretty good idea of when to start braking. On our first flying lap in the Z4 roadster, we thought we were playing it safe. Little did we know that the Z4’s tires have all the braking traction of a greasy sponge. So our braking point wasn’t early; it was late. Real late. We sailed past the turn-in point with the Z4’s ABS furiously pulsing the pedal and promptly ran out of pavement, harmlessly dumping the car into the mud.

That lap was a dud anyway since we hadn’t yet learned how to effectively battle the evil microprocessor that operates the Z4’s seven-speed dual-clutch gearbox. The transmission’s so-called “manual” mode—a perfect example of false advertising—is not, strictly speaking, manual. It automatically upshifts at redline and won’t shift when the car is side-loaded, something that happens with regularity on any road course. Worse, when we tried to hold a relatively high gear while exiting a corner—to let the engine’s low-end torque reserve do its thing—the transmission downshifted when we accidentally engaged the gas pedal’s kickdown switch. BMW offers no manual transmission in the 35is model. Combine that frustration with the Z4’s understeer-biased handling, and you end up with a capable, but not particularly fun, two-seat BMW.

Shouldn’t the BMW roadster be the sports car of the lineup? The Z4 looks cool, makes the right noises, and feels appropriately stout when you nail it. But it fails to engage the driver as a sports car should. When we drove the 1-series M coupe—which has the same engine but an edgier suspension—it was so good that our knees were quivering after a few laps. The Z4 should take notice.

Mercedes-Benz C63 AMG Coupe – LL3, 3:06.3

We wanted to spend all day lapping VIR in the intoxicating C63 AMG coupe. The big 481-hp, naturally aspirated V-8 feels like it burns nitrous and sounds like it spits fire. The brakes arrest speed like a state trooper. But the real reason we wanted to go back out on the track was to try to shave a few more tenths off its best lap time of 3:06.3.

The C63 AMG coupe bested the C63 AMG sedan we ran here in 2008 by a couple of tenths, but we’re convinced there’s more to be had. Our coupe weighed only seven pounds more than the sedan and, with the optional AMG Development Package ($6050), brought 30 more horsepower to the track. Peak speed rose to 142.0 mph, a gain of 3.0 mph over the four-door.

But the extra power isn’t the whole story. All 2012 AMG-tuned C-classes (both coupe and sedan) have new springs, shocks, bushings, and additional camber at every corner. It makes for an all-around more civilized ride. The tail now stays in place unless you really goad it; and the suspension, while still firm, is less upset by curbing and rippled pavement. There’s stability right to the edge, but when it breaks loose, all 3996 pounds want to keep right on sliding.

So we’re left with the familiar track-day lament: If we were given just one more lap, we could have entered the uphill esses a bit quicker or carried more speed into sector three . . . and so forth. But, even though the coupe took more time through those sectors than the sedan, the overall time still trumped the four-door’s. And the C63 AMG is quicker than the BMW 1 series M. Not too shabby for a two-ton luxury sports coupe.

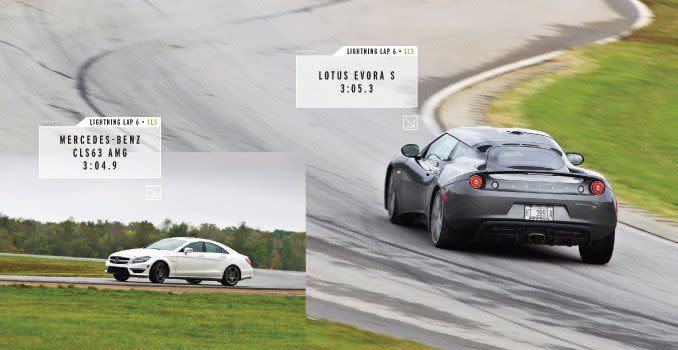

Lotus Evora S – LL3, 3:05.3

At last year’s event, the Evora left us wishing for more power. More has arrived. Thanks to a supercharger, the Evora S makes 345 horsepower, 69 more than the naturally aspirated version. Peak speed rises from 128.7 mph to 135.5 mph. In the end, though, the Evora S put down a lap that was just 3.0 seconds quicker than the regular-issue Evora.

Look at the sector times, and you’ll see why the 25-percent more powerful Evora S doesn’t spank the base car. Our chosen sectors are more about handling finesse than outright power, and since the Evora’s chassis is unchanged, the times are all remarkably similar. Most of the three-second delta comes from the front straight and the back straight, where the extra horsepower makes a difference. That said, one sector where you can see the extra power is in the uphill esses of sector two. The Evora S enters at 116.6 mph, a gain of 5.4 mph, and leaves the sector going 7.6 mph faster. The Evora S slices a half-second off the standard Evora’s time in sector two.

What we liked last year about the Evora is all here: The steering communicates every nuance of the surface and how much or how little the front tires are slipping. The chassis remains sensitive to load transfer. Trail-brake or fly into a corner too fast, and the rear end will swing around; add power early out of a low-speed corner, and the Evora will understeer. Cornering grip continues to feel strong enough to slosh all your blood to one side of your body. Strong brakes and a firm pedal still erase triple-digit speeds with ease.

What we hate about the Evora—the sloppy shifter—remains. Shifting from second to third is still an act of faith as the third-gear gate is dangerously close to first. Downshifts into second are still met with a lot of resistance from the synchros. Maybe the newly available six-speed automatic isn’t such a bad idea after all.

Mercedes-Benz CLS63 AMG – LL3, 3:04.9

In this year’s battle of the four-door heavyweights, Mercedes proves that a big competitor can be graceful. The CLS63 weighs in at a not insubstantial 4308 pounds, which should inflict a beating on tires and brakes. Yet, the Benz powered around the course coolly, and its 3:04.9 lap was quicker than both of the flyweight Lotuses, the Evora S and the Exige S 260 Sport. If Colin Chapman were still alive, the procession of heads rolling at Hethel would make the French Revolution look like a minor skirmish.

Mercedes seems to follow the old axiom that weight is largely an engine-builder’s problem. And so the CLS63 is packed full of glorious, ludicrous horsepower. Our test car came with the optional AMG Performance package, which means its twin-turbo V-8 puts out 550 horsepower (the same as the Porsche Panamera’s turbo V-8). As with the Porsche, the Benz positively inhales straights. But the Benz lacks the Porsche’s four-wheel drive, so it struggles to get all its power down coming out of the slower corners. And the Benz’s seven-speed automatic can’t quite match the Porsche’s dual-clutch transmission’s instant shifts. Hit the Benz’s upshift button, and there’s a one- or two-count before anything happens. This is no tragedy in a street car, even a sport-tuned one; you can learn to deal with that behavior, but it’s far from ideal on the track.

While the Porsche feels absurdly long, the Benz feels heavy, which is strange since it’s 126 pounds lighter than the Panamera. The tires make up for their relatively low grip with relaxed breakaway characteristics. You can overcook a corner and still recover.

It used to be that Benzes were lazy-feeling cars. The CLS may not be quite as sharp as the Panamera, but it’s far from inert.

And it’s 80 grand cheaper. A “value” Benz? That’s nearly as strange a concept as a five-door Porsche.

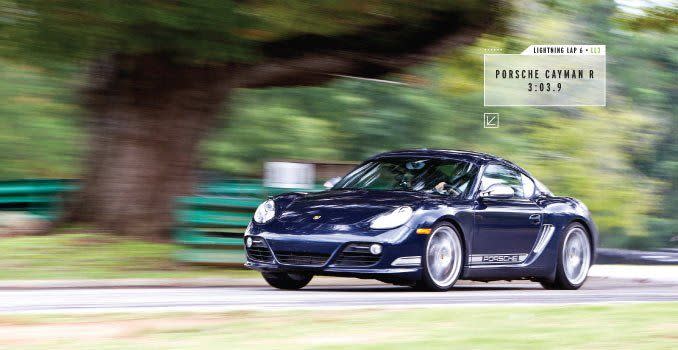

Porsche Cayman R – LL3, 3:03.9

Last year, we brought the Porsche Boxster Spyder to VIR. It floored us with its easily exploitable grip, its frontal-lobe-bruising brakes, its racing seats, and its quick-shifting dual-clutch gearbox. This year, we brought along its hardtop twin, the Cayman R.

So it should come as no shock that the Cayman R crossed the finish line just 0.1 second behind the Spyder on its best lap. But wait—shouldn’t the hardtop have been quicker than the roadster? Let’s examine the evidence. At 3048 pounds, this Cayman R is 15 pounds lighter than the Spyder. Credit carbon-ceramic brake rotors (28-pound total reduction) and a lack of air conditioning (last year’s Boxster Spyder had A/C) for canceling out the extra weight of the Cayman’s roof. The Cayman R also has 330 horsepower to the Spyder’s 320. We suspect the power difference is due to marketing more than engineering (all Caymans enjoy a claimed 10-horse advantage over Boxsters). Our proof? The Cayman R was only 0.4 mph faster on the straight than the Spyder with its top off.

In the uphill esses, there were no significant differences in track performance between the two cars. The Cayman felt a bit more secure than the Boxster and was less upset by the curbing, which allowed for a quicker, 121.3-mph entry speed and a 112.2-mph average (the Spyder entered at 112.1 mph and averaged 106.2 mph). We suspect the difference is due to those lighter brakes. They aren’t used in the esses, but even when you’re not squeezing them, the R’s carbon-ceramic rotors are seven pounds lighter per corner than the Spyder’s iron units. Reducing the unsprung weight improves the Cayman R’s wheel control over the curbing and the driver’s confidence at speed. Theory two: The driver (same as last year) grew a pair.

Other than sector two, the Spyder was a few tenths better in a couple of corners to take the lead over the Cayman R. We’ll close by arguing that the Spyder’s lower center of gravity gave it a minute advantage around the rest of the track. Not a huge advantage, but neither is 0.1 second.

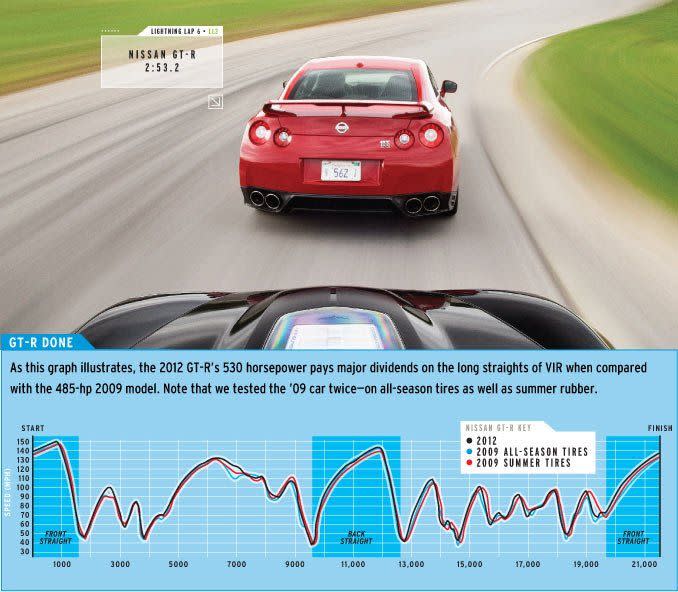

Nissan GT-R – LL3, 2:53.2

Since its launch in 2008, the GT-R has been the world’s best “numbers” car—a machine created and honed to post stellar lap times and performance figures but so aloof and cold as to remind you of a video game. Well, apparently Mr. Roboto has been wintering in Italy because this car now has a soul.

Like previous GT-Rs, with four-wheel drive, a dual-clutch gearbox, and faultless brakes, the tweaked-for-2012 version still feels like a car any ol’ chimp can take right to the hairy edge of the limit. Get in, press a few buttons, and the GT-R pops out internet-bragging figures. The difference now is that you, the driver, actually feel like you’re part of the equation.

The 2009 GT-R rode like a go-kart, felt indifferent on the track, and brutalized its front tires. The ’12 GT-R, with an extra 45 horsepower, new tires, and a tweaked suspension is still uncomfortably stiff, but at least there’s a payoff for the pain. It bites into corners crisply and decisively, and it’s not as prone to understeer.

And let’s not forget that it’s faster, too. The GT-R peeled 2.4 seconds from its previous best time to post a 2:53.2. It’s now the eighth-quickest car we’ve ever put to the Lightning Lap test. It’s not that far behind the Corvette ZR1, and it induces far fewer cardiac events while it’s at it. The GT-R is no longer just a numbers car, but it’s still the king of accessible speed. The slightly more powerful 2013 GT-R [see comparo] wasn’t available for this event.

Chevrolet Corvette ZR1 – LL3, 2:50.7

How much are stickier tires worth? About a second according to our clock. With the Michelin Pilot Sport Cups, which are lightly disguised race rubber, the ZR1’s best lap was 1.1 seconds quicker than it was on more roadworthy Michelin Pilot Sport PS2s.

In the six-year history of Lightning Lap, only the Viper ACR and a pair of Moslers were quicker than this ZR1. And those track-day specials are so stiff, so uncompromising, that you’d have to be a special sort of masochist to use them as daily transportation. That’s not the case with the Chevy, which has automatic climate control, heated seats, and a little give in its legs.

The road-car-versus-thinly-veiled-race-car distinction is not a trivial one. Cars with this absurd level of horsepower (638 in the ZR1’s case, 78 more than Pratt & Miller’s Le Mans race Vette) are terrifyingly quick. And only a perfectly track-tuned suspension imparts the confidence required to use all of the available performance.

Generally speaking, the ZR1 has excellent hardware for the job. The new tires, predictably, have enormous grip. When you finally arrive at the limit of adhesion, the Michelins break away gradually. The brakes are as good or better than the best Porsche units. And the Performance Traction Management (PTM) stability-control system is fantastic. There are five PTM settings with intervention thresholds ranging from “Help, Mommy! I’m scared!” to “I’ll just want a little nudge now and again.” The latter, PTM 5, is so good we used it for our hot laps.

But we never got totally comfortable in this sometimes darty, skittery car. There was always this little voice telling us we should have bought that life-insurance policy. And that momentary doubt causes your foot to involuntarily lift off the gas. We’re not sure we can pinpoint the cause of our uneasiness. Maybe the street-tuned suspension is too soft. Maybe the bushings are too compliant. Or let’s blame the improved but still under-supportive seats. Yeah, let’s go with that.

LL4 ($129,000–$249,999)

Porsche Panamera Turbo S – LL4, 3:00.7

We’ve clocked the regular Turbo version of Dr. Seuss’s Porsche at 3.3 seconds to 60 mph, so we know it is absurdly quick for its size. But who could have guessed that this new Turbo S version could outrun a 911 GT3 and equal the 3:00.7 lap time of the Ford GT on a racecourse as demanding as VIR?

Not us—even after we climbed from behind the wheel. True, it has 550 horsepower, but the kick dulls after a few laps. You’re left with a serene and heavy-feeling five-door that’s so long it feels like you’re pulling a trailer. We nicknamed it the “The Bus.”

The Bus does the unexpected. Its steering transmits those minute signals that relay available grip. The rear end comes around if you’re sloppy, but it’s easily catchable. So the Panamera goads you into using all it’s got. In the climbing esses, the section of the track that contributes to the graying of a few hairs on every pass, the Panamera was unflappable. Sure, some cars are faster through there, but few do it at the Panamera’s 116.4-mph average with such utter calm.

Like all Porsches, the brakes are tireless, and with standard all-wheel drive, even your sister could master corner exits.

This is not to say the Panamera Turbo S is perfect. The seven-speed PDK shifts quickly, but it’s too willing to overrule the driver’s commands. And the gear indicator is buried in the gauge cluster, so it’s tough to read at a glance. And then there’s the Porsche’s styling and its nearly $200,000 price tag.

But there is no denying the stunning capabilities of this magic bus.

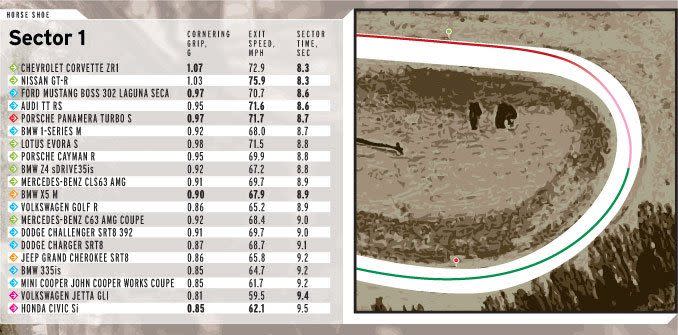

• Sector one is one-and-a-half corners of a two-corner complex at the end of the front straight. this section lies at the track’s lowest elevation.

• The GT-R’s all-wheel drive allows it to hold a tighter line here than the ZR1 while putting down its power and setting up for the next left-hander.

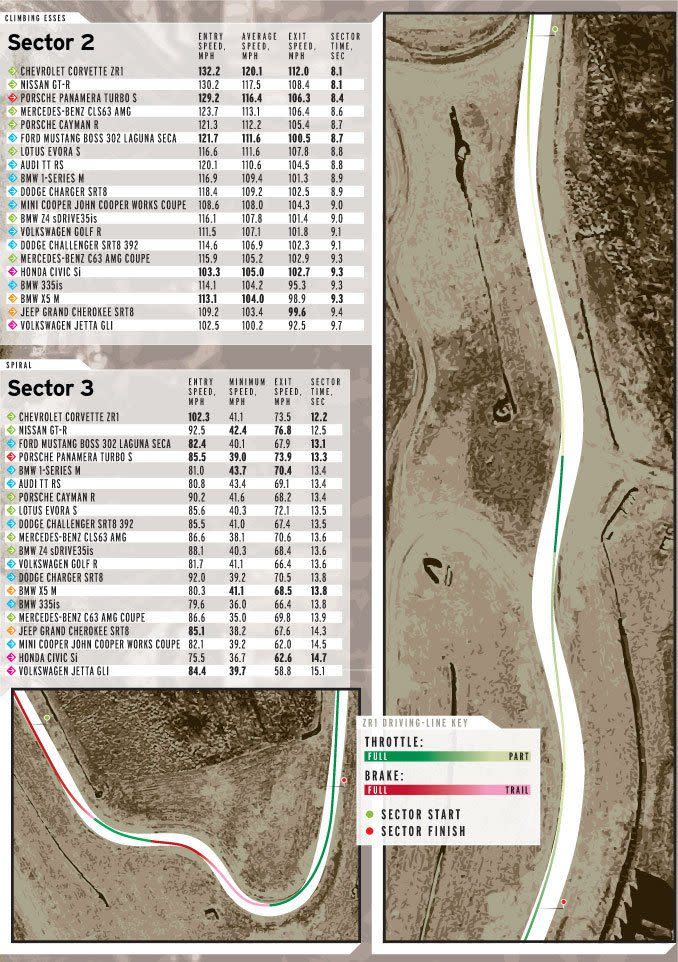

• Entering sector two at more than 100 mph is as much a test of a driver’s will as a car’s ability. Until the driver is comfortable, he may find his throttle foot shaking out of a sense of self-preservation.

• The first left-hand corner is the sector’s tightest. The next two turns open up a bit, and the final right has a radius identical to the second’s.

• “Climbing esses” is a bit misleading. “ROller-coaster Esses” might be more accurate. Although you finish higher than you start, the second and the final corners’ apexes are on crests where cars get light and unsettled.

• The final right-hand turn sets the car up for an off-camber blind left that can make or break a lap. It’s just as hairy as the esses.

• Before the 50-foot drop is an uphill braking zone where cars with race-proven brakes, like the ZR1, can maximize deceleration.

• Sector three is VIR’s “spiral.” it’s the Appalachian version of Laguna Seca’s corkscrew, Blind entry and all.

• Late apexing the last corner requires patience. when it’s accomplished, the reward is a great line of attack for max mph on the mini-straight that follows.

• Sector four is another technical passage that tests a car’s limit balance. It’s uphill and fast.

• To be quick through here means the driver must fully exploit the friction circle, making tiny throttle adjustments to control a car’s line.

• VIR calls this “hog pen.” we call it sector five. it’s the final sequence in a lap and the final descent of the hill climbed in sector four.

• Like “bitch” at the end of the back straight, this right can be navigated a few different ways. the ZR1’s line is slightly tighter than the GT-R's, But their times are almost identical.

We’ve run Lightning Lap six times now, amassing a ton of blistering lap times around VIR. You can see them all in the table below, which can be sorted by time, vehicle, and Lightning Lap class. Click the Time, Car, and Class headers to sort by each parameter.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos