The Lost City of Fordlandia

The easiest way to get there is to fly. After touchdown in the city of Manaus, Brazil, you boat down the Amazon, then up a tributary called the Tapajós. The last real sign of civilization is the beachside tourist outpost Alter do Chão. Hours upriver, the lost city of Fordlandia appears portside. Industrial buildings with shattered windows rise above rows of homes. A rusting water tower stands as the highest structure. Well over 2000 Brazilians live here, foraging off the dreams of the past for subsistence. One resident, a retired milkman, recently told a reporter while walking on the main drag: “This street was a looters’ paradise, with thieves taking furniture, doorknobs, anything the Americans left behind. I thought, ‘Either I occupy this piece of history or it joins the other ruins of Fordlandia.’”

This story originally appeared in Volume 5 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

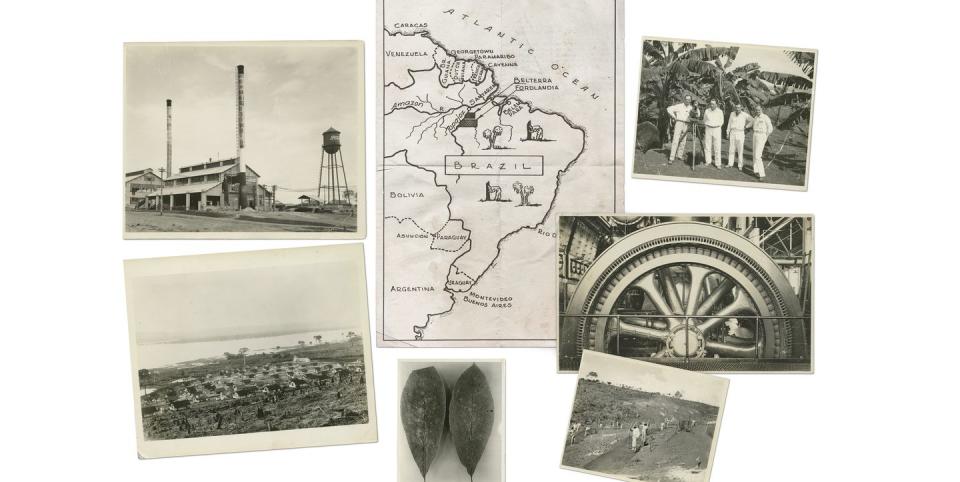

Welcome to Henry Ford’s utopian experiment gone wrong, one of the world’s strangest lost cities. The story began in 1927, when Henry Ford dreamed of a factory town attached to its own rubber plantation in Brazil. He planned to produce two million tires per year there, sourcing raw material where rubber trees grew wild. That same year, Ford launched the Model A to replace the Model T. Business was good, and there was money to spend.

Just as he’d dreamed up the integrated assembly line and the largest factory on earth, the Rouge plant in Dearborn, Ford would now birth the first fully planned modern American city in the Amazon. He wanted more than just rubber for tires; he wanted to take “uncivilized jungle people” and turn them into “fully realized men,” as author Greg Grandin put it in his book Fordlandia.

“We are not going to South America to make money,” Ford announced, “but to help develop that wonderful and fertile land.”

Ford negotiated rights to almost 6000 square miles on the Tapajós River for $125,000. Up it went: rows of clapboard homes (designed in Michigan, naturally), dining halls, a school, a hospital, a church, a recreation center, a community pool, a theater to screen Hollywood movies, a golf course, a sawmill, and a powerhouse to deliver electricity to the entire town. Ford installed direct radio and telegraph communications from his home office in Dearborn all the way to the Southern Hemisphere, connected to the city he named Fordlandia.

You can imagine Brazilians who had never had indoor plumbing perfecting their backhand on one of Fordlandia’s tennis courts or doing the rhumba in Fordlandia’s dance hall. A visitor who witnessed the city in its third year breathlessly recorded his impressions: “Electricity and running water in native homes were miracles undreamed of before Henry Ford went to the tropics. . . . Fordlandia, an up-to-date town with all modern comforts, has been created in a wilderness that never had seen anything more pretentious than a thatched hut.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, this story turned dystopian. Not all of Fordlandia’s residents were happy about being colonized and Americanized. Within a few years, Ford’s planned city became mired in problems: rioting factions of rival workers, revolts among laborers forced to adopt American culture and cuisine, disputes among the management and the botanists in charge of the rubber trees. Because Ford forbade alcohol, tobacco, women, and even soccer, locals created a rival town up the river, which they called the Island of Innocence, offering every vice banned in Fordlandia.

By the time Henry Ford II took over management of Fordlandia, the wheels had fallen off this experiment. In fact, the writer Aldous Huxley based his dystopian vision of future London on Fordlandia in his 1932 novel, Brave New World. Henry II sold the land back to the Brazilian government, losing millions in the process. As quickly as the Americans came, they left.

Most of Fordlandia’s original buildings still stand. There’s a local bank, a pharmacy, and a watering hole called Bar Do Doca, but no Ford rubber factory. Henry Ford himself never visited the place. If he were alive and asked about it today? He might shrug it off with a version of his famous line: “History is more or less bunk. . . . The only history that is worth a tinker’s damn is the history we make today.”

ORIGINAL THINKING

Henry Ford was the 20th century’s world champion of weird ideas. Not all of them stuck. These did.

Soy milk

Today, Starbucks serves oceans of the stuff. But in the 1920s, nothing like soy milk existed. Until Ford made his own.

Charcoal

In 1919, Ford teamed with Edward Kingsford to build a timber mill, for wood for cars. They took the leftovers and invented charcoal briquettes, marketing them under the Ford brand. You can still buy them, only now the brand is called Kingsford.

Whole-foods diet

That’s what we call it today; in Ford’s time it had no name. But he believed in a daily diet of numerous small meals rather than three big ones, and no meat. He even created his own version of tofu.

Farm-raised plastic

Nowadays, earth-conscious companies produce plastics from organic materials. In the Thirties, Henry Ford used a process called chemurgy—applying chemistry to make plastic from plants. To prove it would work, he built a vehicle with a body made of soybeans, the 1941 Ford Soybean Car.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos