My Mom Was Everything I Wanted To Be. Then She Became Addicted To Oxycontin.

The author (right) with her sister Jessie and their mom at the Jersey Shore, around 1988. (Photo: Courtesy of Kristin Fasy)

I dashed through driving rain toward the detox and rehab center, a grocery store bouquet of gerbera daisies shoved under my arm. In the lobby, I approached the receptionist’s desk with a too-bright smile.

“Hello,” I said, shrugging out of my coat. “I’m here to see my mother.” It was May 12, 2019: Mother’s Day.

A week earlier, my phone buzzed as my husband and I waited on the tarmac at Denver International Airport, bound for a much-anticipated island vacation.

“Ignore it,” Andy said when he saw my mom’s name on my phone screen. But I couldn’t.

“Hi Mom,” I said, turning my eyes toward the ceiling as if I might find serenity among the call buttons and task lighting.

“I’m not good, Krissy,” she squeaked, and I felt a familiar emptiness in my chest where compassion used to live. Calls from my mother ranged from panicked requests for money, to tearful apologies for being a burden, to stream-of-consciousness monologues about growing up in 1950s Philadelphia. They were rarely two-way conversations, and it was never good news.

As the plane began to taxi, she told me she was feeling bad, at her wit’s end, she said, and I murmured calming words as the flight attendant shot me a warning look. The truth was, I felt nothing but resentment. Raising my own two kids was hard enough; I shouldn’t have to mother my mother, too.

“It’s gonna be OK, Mom. I have to go. I’ll call Jessie.” I hung up and texted my sister. “Just talked to Mom. Shit show as usual. I think she’s ready for rehab.”

Our mother wasn’t always like this. In the ’90s she was funny and vivacious, the queen of Sparrow Lane. She organized all the block parties in our New Jersey neighborhood, hosted all the pre-prom photo ops, and turned Led Zeppelin up loud when she vacuumed. When she and my dad got home late after nights out, she would tiptoe into my room and place reverent kisses on both my cheeks, smelling like Calvin Klein’s Obsession and chardonnay. “My girl,” she would whisper as I feigned sleep. My mom.

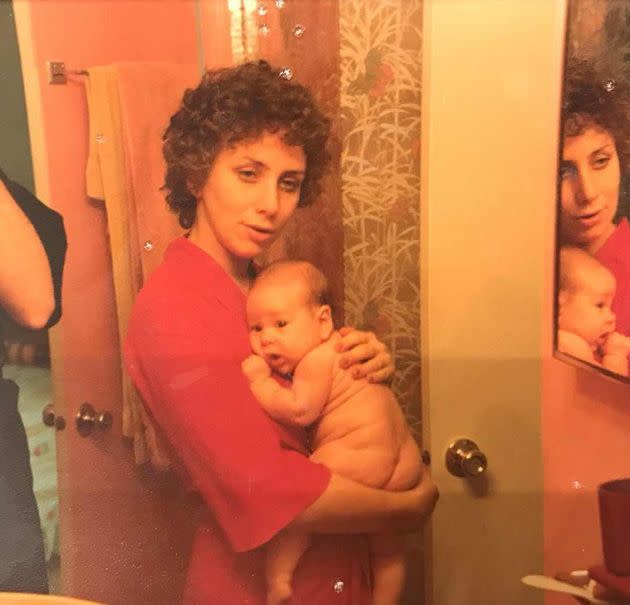

The author and her mom, just a few days after she was born, in 1979. (Photo: Courtesy of Kristin Fasy)

When I was a teenager, she got sick. Mysterious nerve pain and “brain fog” kept her in bed, and the block parties and nights out stopped. The doctors diagnosed Lyme disease, but none of the expensive treatments they tried seemed to work. Then they prescribed Oxycontin. While life moved forward for me ― I went to college, moved to Colorado, got married and had kids ― it slowed to a crawl for my mother.

My parents kept searching for a cure, but as the doctor visits increased and their savings dwindled, there was only one constant in her life: oxy. It took me too long to realize that her remedy had become the central problem, and by then the mother I knew was long gone. I started sending money home instead of visiting and avoided her phone calls; when I said “I love you” it felt like a lie.

Back on the plane, I turned my phone off and slid into vacation mode ― compartmentalization comes easy when you’ve been doing it most of your life. For a week, I sunbathed, drank margaritas, swam in the ocean, and took beach selfies with my friends. When I got home, I called my sister. “How’s mom?”

“In rehab,” she said. “You should probably come home.” A few days later, I was back at the airport, headed for Hanson House.

The receptionist pushed a clipboard toward me. “Sign in, and please remove your shoelaces. Oh, and you can’t bring those in,” she said, reaching for the flowers. I handed them over, trying to work out how someone might use a daisy as a weapon. A young woman sitting nearby smiled at me, and I noticed she was wearing slip-on shoes. Not her first rodeo, I thought.

The receptionist signaled that I could go upstairs, eyeballing me one more time like I might have a coiled length of piano wire hidden up my sleeve. On the second floor, a smiling young man in scrubs greeted me. “You Helen’s daughter?” I nodded. “She’s a sweetheart, your mom,” he said as he led me down the hall, and I was surprised by a sudden sluice of tears.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos