NASCAR's Return to North Wilkesboro Brings Back Flood of Memories

NASCAR announced on Thursday that it was bringing Cup Series racing back to North Wilkesboro Speedway in the form of the All-Star Race 2023.

The last Cup race there was in 1996.

NASCAR Cup racing at North Wilkesboro Speedway dates back to NASCAR's inaugural season in 1949.

I can remember with uncommon clarity leaving North Wilkesboro Speedway that Sunday night on what we all were certain would be the old track’s last day. '

Sept. 29, 1996. Hours earlier, Jeff Gordon had outrun Dale Earnhardt by almost two seconds to win the Tyson Holly Farms 400, which had been advertised all year as the final NASCAR Cup race in the speedway’s history.

Gordon won races in those days—and a lot of them. It seemed appropriate—and, at the same time, oddly inappropriate—that Gordon won that Sunday at North Wilkesboro. He won 10 races that season, after all, and the NWS win was his third in a row.

But North Wilkesboro, steeped in the grime and glory of NASCAR’s pioneer days, was not of the Jeff Gordon era. North Wilkesboro was painted in the colors of the Flock brothers and Buck Baker and Curtis Turner and track operator Enoch Staley, men who grew up in the days when the only thing modern about speedways might be a string of bright new light bulbs hanging across the track at start/finish.

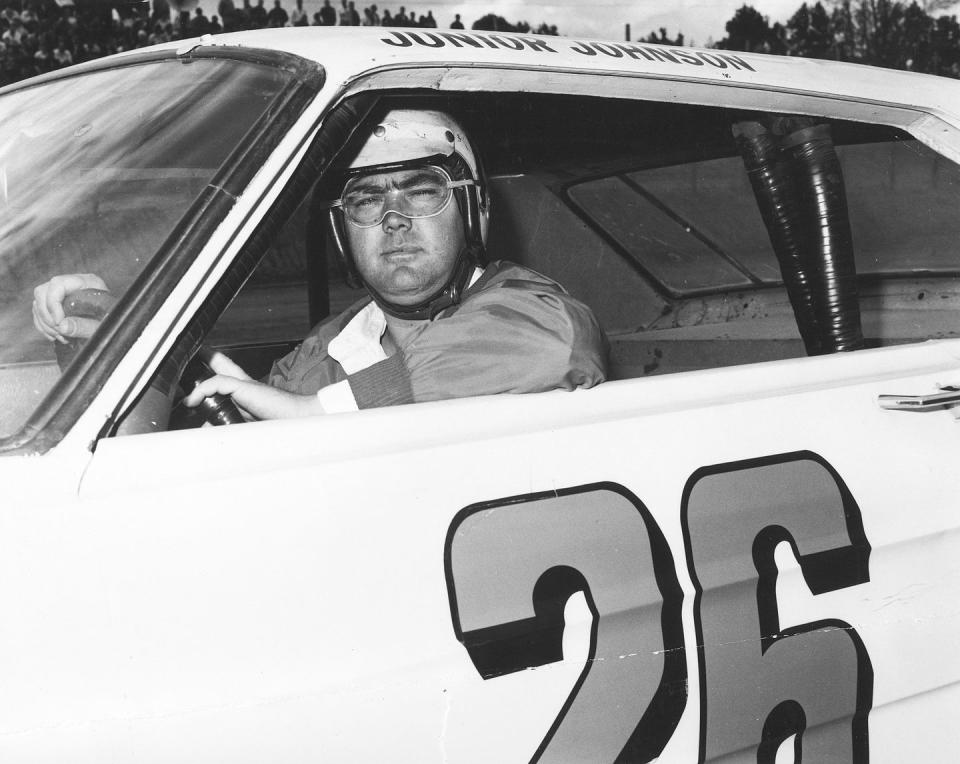

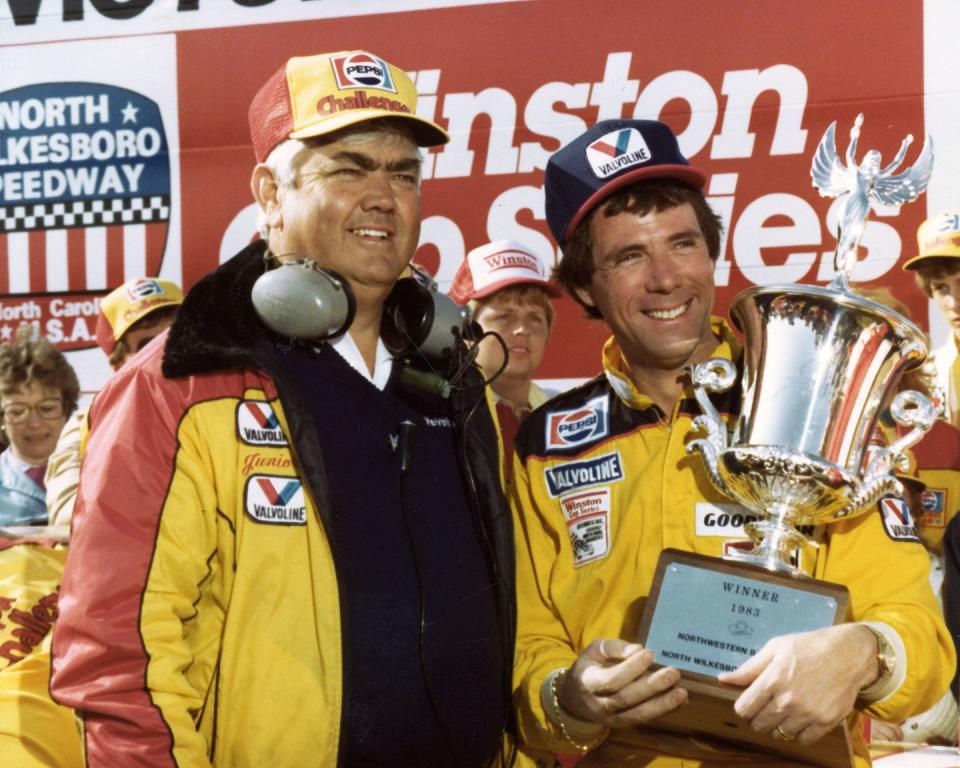

And Junior Johnson. He personified North Wilkesboro Speedway more than any other individual.

Growing up on the edge of the nearby Brushy Mountains and a moonshine hauler even though he was so young he barely could see over the steering wheel, Johnson was both the guy owning the next farm down the road and a legend in his own time. He was a rough-hewn country boy who drove cars fast—legally and illegally—and showed no fear and backed away from no man.

He was the perfect hero for the locals, and they came to see him as the de facto king of their speedway. He came from the same dirt and, unlike most of them, raced on it.

They named a grandstand after him at the speedway, and to think that they might close Junior’s place was unthinkable in those days, for NASCAR’s two annual visits with its Cup circus had provided North Wilkesboro’s lifeblood since 1949. The drivers, the cars, the fans – they all came to town in the spring and fall, and it was as if the speedway grounds were hosting a carnival that would never end. The local mom-and-pop motels and restaurants – we’re talking about you here, Williams Motel and Captain’s Table – saw the cash flow in as manna from heaven, even if it was the hellions of the fast track who brought it.

But it was all too real that fall Sunday. Gordon finished all the post-race hoopla, and the last fans wandered down the hill to their cars. Empty beer cans and food wrappers dotted the parking lots.

Twilight fell on North Wilkesboro Speedway, and there would be no sunrise.

Even in the track’s final years as a stop on the Cup tour, its best days were long gone. Paint was peeling, concrete walls were cracked, buildings were of another time. When the last NASCAR vehicle left that day, wilderness moved in. Few would have been surprised to see the track eventually consumed by kudzu.

Year after year, the speedway withered. From the main highway, it looked like a place of ghosts. Some would say they were real.

Harold Call, who ran a local restaurant, described the feeling of dread in those last days: “You know when you finish high school and the fall comes and everybody goes back to school and you don’t? You feel left out, like you’re not a part of it anymore. That’s the kind of void in our hearts right now.”

The track was a unique stop on the NASCAR tour. At no other track did local cooks prepare food – fried chicken! banana pudding! – for media members. At no other track were VIPs sent home at the end of the day with a jar of the local “champagne,” with a peach bobbing in the middle. At no other track did one straightaway run downhill and the other uphill.

Some Memories from Those Days

• Davey Allison, after winning the First Union 400 in April 1992, sitting on the back of a pickup truck in the infield and signing autographs for a huge line of fans. He signed and signed until the end of the line reached him, hours after the checkered flag.

• Junior Johnson, coming to the rescue of a North Carolina journalist who had written an article critical of the track, a story strong enough to fire the anger of some local toughs. Johnson, a man you didn’t want to mess with, stepped in to sooth tensions.

• Darrell Waltrip ending a 34-race winless streak by reaching victory lane in April 1991, his first win with his own team.

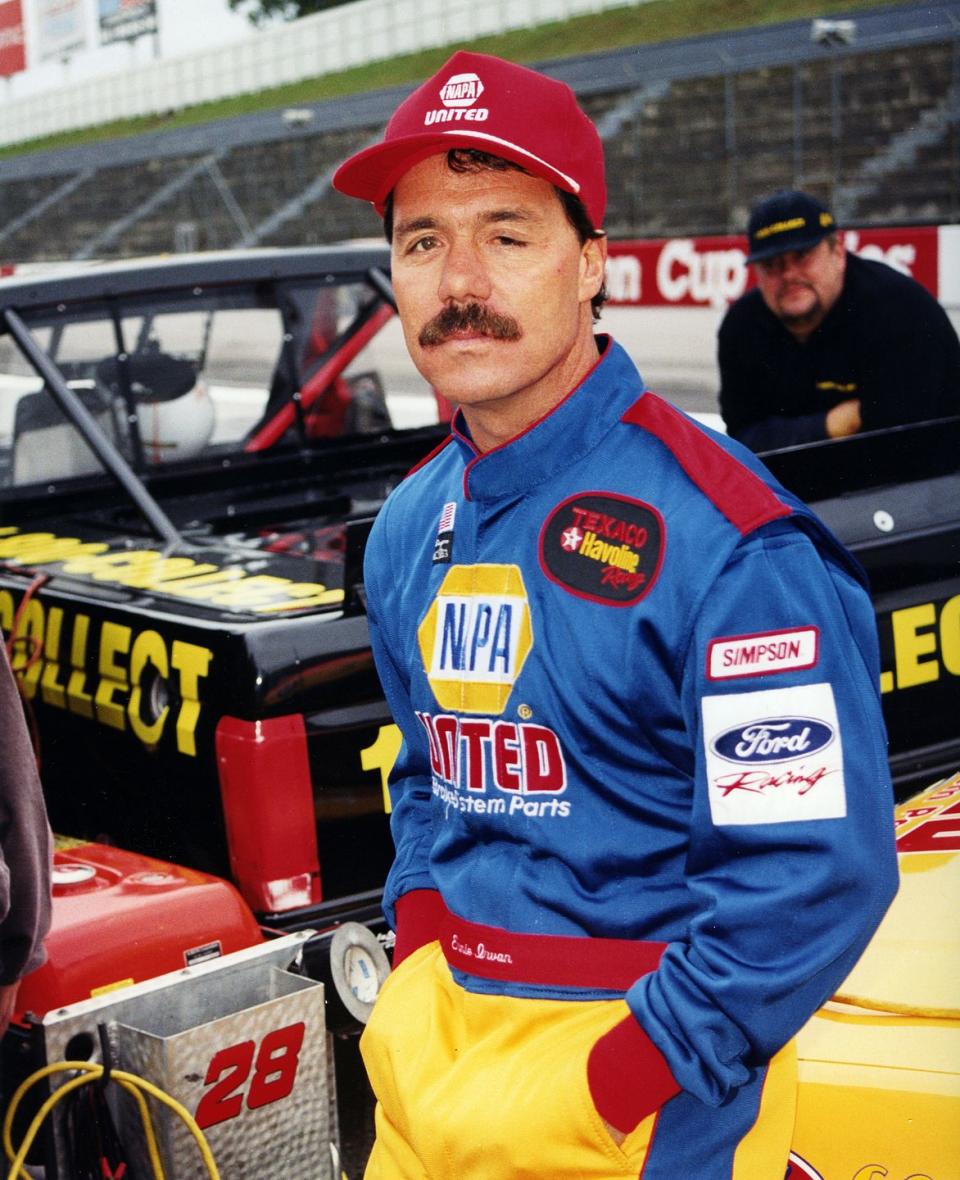

• Ernie Irvan returning to the driver’s seat at Wilkesboro in October 1995 after suffering near-fatal injuries in a crash at Michigan Speedway in August 1994. Remarkably, he finished sixth.

• Flossie Johnson’s biscuits. Once the wife of Junior Johnson, she hosted weekend meals that old-timers still remember fondly.

Now comes news that the speedway, largely forgotten for so long, will hear the thunder of Cup cars once again. The work of many both inside and outside the community has breathed new life into the track, and its revival has been impressive enough to earn NASCAR’s notice – and its 2023 All-Star Race.

There will be new memories at the old track.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos