Pagani: The Man Who Signs Every Car

A mistake turns out to be a stroke of luck. This rented Fiat Panda is a Group A special of such pared-back basicness that the only source of onboard navigation is my phone, balanced on the dashboard. After arriving in Italy, I ordered Google to take me to Pagani, but the algorithm set the destination to the company’s semisecret R&D base rather than the factory-museum. I get to the skunkworks just as the gates motor open so a prototype disguised in black-and-white wrap can pass, its sonorous departure confirming that future Paganis will sound as good as the current ones. And then, as the gates begin to close, a short figure with silver hair exits on a bicycle. It takes a moment for me to realize that this is Horacio Pagani himself, pedaling to the factory a half mile distant. It feels as special as catching a glimpse of Enzo in his raincoat.

This story originally appeared in Volume 12 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Pagani the man is also Pagani the brand, with the values of both exemplified in the spectacular factory in San Cesario sul Panaro, near Modena. This is just 10 miles from Lamborghini’s base in Sant’Agata Bolognese and barely farther from Ferrari’s home in Maranello. You need a huge amount of talent and self-confidence to hang a shingle as a supercar maker in Italy’s Motor Valley. But you also need an appropriate name, something that won’t sound out of place when applied to a seven-figure exotic. So we’re lucky that Horacio Pagani kept the one his grandfather bore when he emigrated from Italy to Argentina in the late 19th century. What if his family had married into the earlier wave of Welsh settlers? It’s hard to imagine a Huayra with “Rhys Jones” etched on the badge.

Pagani was drawn to Modena to work for the supercar industry, arriving broke and unable to speak Italian in 1982. He rose through the ranks to do much of the engineering for the carbon-bodied Lamborghini Countach Evoluzione prototype, then set up his own composite company. But he didn’t want to just work for others, and in 1992, he began work on his own supercar project. It took his tiny team seven years to create and launch the Zonda, a combination of carbon-fiber gorgeousness and Mercedes V-12 power, the engine deal brokered in part by Juan Manuel Fangio.

Finished to a standard that made contemporary supercars feel thrown together, the Zonda was an instant sensation. Pagani was soon working on faster and sharper-edged versions and then its successor, the Huayra. Yet the company’s sales figures have always been tiny. Since its founding, Pagani has produced only 450 cars. Ferrari makes that many every two weeks; Lamborghini in just over three. As Italy’s longer-established weavers of automotive dreams have chased bigger volumes, Pagani has become the country’s true bespoke-supercar maker.

Pagani’s factory feels only slightly less special than Willy Wonka’s. Inspired by the traditional Italian village piazza, it was built with the same attention to detail as the cars made there. The bricks for the walls were carefully selected to be as close as possible to those in Modena’s medieval center. When, late in construction, earthquake-resilience codes became stricter, Horacio took inspiration for the necessary metal reinforcements from the design of the Eiffel Tower. The building includes an old-fashioned tower with a huge mechanical clock that chimes on the quarter hour, streetlights chosen to match those in local towns, and washrooms with carbon-fiber basins. Ornamental trees dot the factory floor, and there’s a verdant living wall of plants. Even the most humdrum items are carefully thought out—the trolleys used to haul parts have stitched leather handles like the straps that hold shut the Huayra’s hinging front clamshell. Adding to the surreal atmosphere is the assembly area’s gentle background music, including Nineties rock songs played acoustically on lutes and mandolins.

The main hall is home to both production and a large number of exhibits from the Horacio Pagani Museum, which shares the building; guided tours move around regularly throughout the day. It takes about six months for a new car to get from the construction of the first parts in on-site carbon-baking autoclaves to completion. Finished cars depart less than once a week. When I visit, the factory is well into the run of 30 Huayra Rs, with cars sitting in various stages of assembly in each bay.

Getting close allows me to see both the workers’ unhurried pace—the atmosphere is more operating theater than automated production line—and the sheer beauty of the engineering. The Huayra R’s mostly hidden door hinges are perfectly designed and finished, color-matched to the similarly obscured suspension wishbones. Clearly, even invisible details have been considered, like the way the release cables inside the doors are routed with geometric exactitude. Seeing me squint at minutiae, a worker beckons me and hands me a tiny hex bolt no more than a half-inch long. Close inspection reveals that “PAGANI” has been engraved on its head.

"Let’s start by saying that these cars are useless. It is very important to understand that you don’t use these cars to take your children to school or to go shopping.” I’m in the glass-sided office that overlooks the production area talking with Horacio Pagani, whose words are being translated by his son Christopher, Pagani’s head of marketing. While this means that grammar slips occasionally—talking about your dad in the first person is tricky—it does give me a chance to ask about the obsession for perfection that obviously drives the company.

“We live in an amazing land with an amazing history: Maserati has more than 100 years, Ferrari has 70, and Lamborghini has 60. There are a lot of reasons for collectors not to buy Paganis because of what all the others have been doing for these decades—which means we have to try harder and harder. That’s why we spend so much time on details.”

It is also why Horacio Pagani’s signature is on every car, not only on miniature aluminum badges but also often with real ink. “When you sign a car, you acknowledge the responsibility of your job. You say, ‘This was me,’” he says. “This is my family’s real name, not one that was invented for the company. This is what it says on my passport. There are many clients who, when they come to collect their vehicle, want me to sign a real signature somewhere on the car—the engine, the rear bonnet. Sometimes they also want the other people who worked on the car to sign it. This is how direct the relationship is.”

Even though a 30 percent stake in the company was sold to Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund last year, Pagani remains a family concern, with Horacio’s wife and both of their sons involved in management. Much of Pagani’s success is due to its closeness to its customer base. The company knows the current owner of every car it has produced. The rising values of early Zondas—many of which are fetching eight-figure prices—mean owners are predictably keen to maintain originality. Horacio Pagani reports that buyers have been getting younger. When the company began, the typical customer was mid-forties or older; now many are in their thirties or even twenties. They are also demanding new and different experiences, which is where the idea for the track-only Huayra R came from.

One thing they don’t want is electrification. “We started work on a full electric-vehicle project in 2018. At the same time, we started having discussions with clients and dealers,” Pagani says. “The result was that none of them saw interest in a fully electric Pagani, which makes it even more challenging for us to create one. Ultimately, we want to do that.”

Pagani admits to being concerned about the approaching end of internal combustion in Europe, where exceptions for makers of exotic cars seem unlikely. His voice turns angry when he talks about the relative insignificance of supercar emissions versus the wider auto industry, or shipping and aviation: “I flew back from Argentina on a Lufthansa Boeing 747. The pilot told me in a 12-hour flight, the plane uses 150,000 liters of gas.” Some hasty notepad calculations suggest the total lifetime carbon emissions for every Pagani ever made is less than that generated by 12 Europe-to-L.A. flights.

But although the green future is on the horizon, it isn’t an issue yet. The Huayra’s replacement, currently known by its C10 design code ahead of its unveiling later this year, will stick with a Mercedes-based twin-turbo V-12 without hybrid assistance. It’s exactly what Pagani buyers want. “We sold those cars immediately,” Pagani says. “The first batch is 99 cars for the world, and we could have sold all of those to North America; there is three times oversubscription there. As of right now, the U.S. and Canada are going to receive 43 cars. They could easily buy 150.”

So why not build more, satisfy demand, and fill the company coffers? Because that definitely isn’t the Pagani way: “The vision is always the same. It doesn’t change since we started. Increase is only based on opening new markets. This is something we think is very important. Exclusivity, numbers, and production go hand in hand.”

With such a loyal, rich, and heavily engaged customer base, Pagani can also make some radical decisions. The C10 will be offered with the option of a manual gearbox, something that Horacio admits makes no rational sense but will undoubtedly add excitement.

“Most of the double-clutch gearboxes are just perfect; there is no reason to go for a manual,” he says. “But if you drive an automatic from Monday to Friday, maybe you want your car for the weekend to be a completely different thing. It is not faster, it is not better. It is just pure emotion."

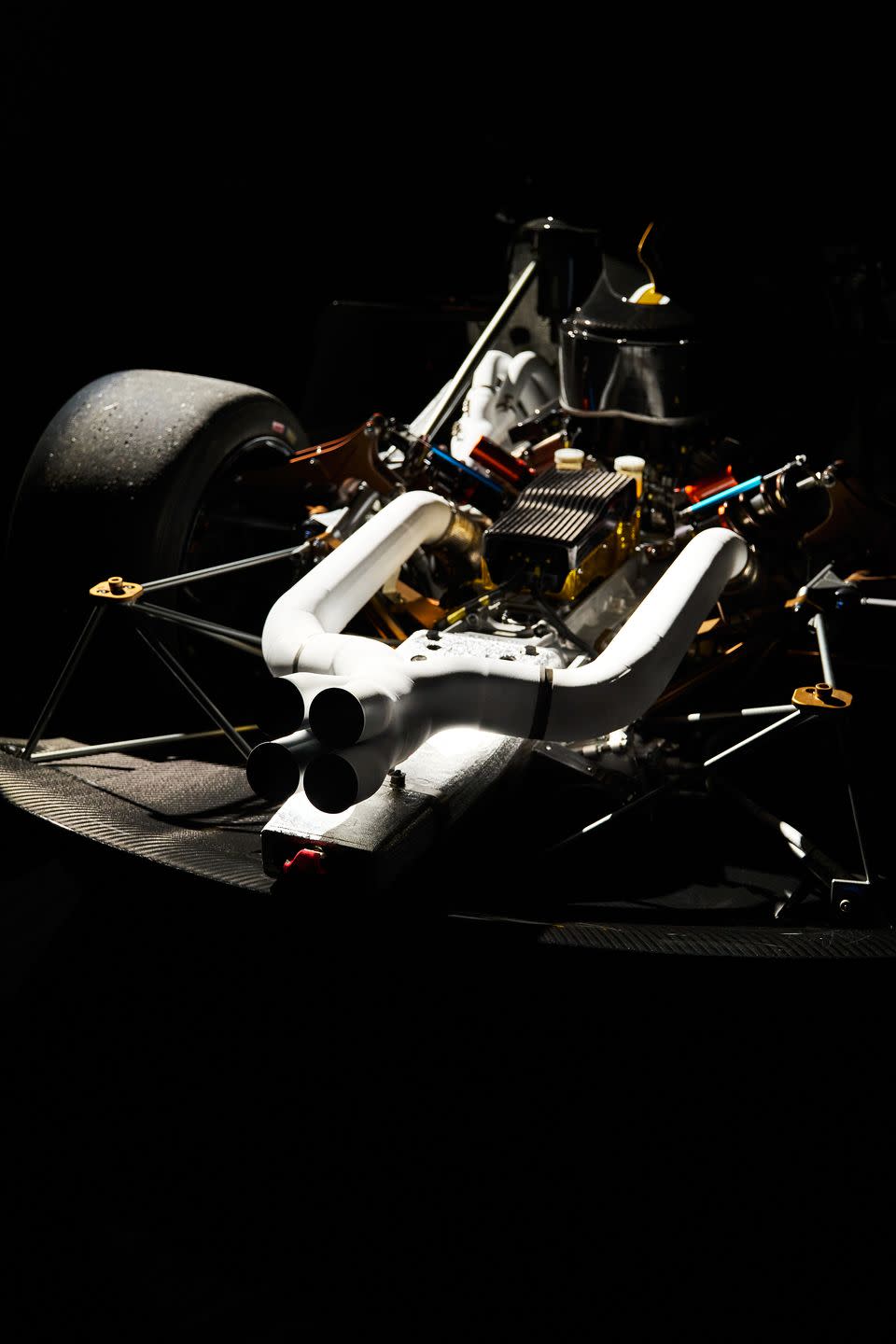

It’s a different day in a different part of Italy, and my emotions are more mixed than pure. There’s an adrenaline-driven high at the prospect of being allowed to drive the factory’s Huayra R demonstrator. But there’s also a strong admixture of trepidation at the prospect of piloting something more potent than most race cars at the unforgiving Vallelunga Circuit near Rome. Before that, there’s also mild confusion as I wait my turn by the pit wall: The Huayra R is the only car on track, so why can I hear what sounds like a Nineties Formula 1 car?

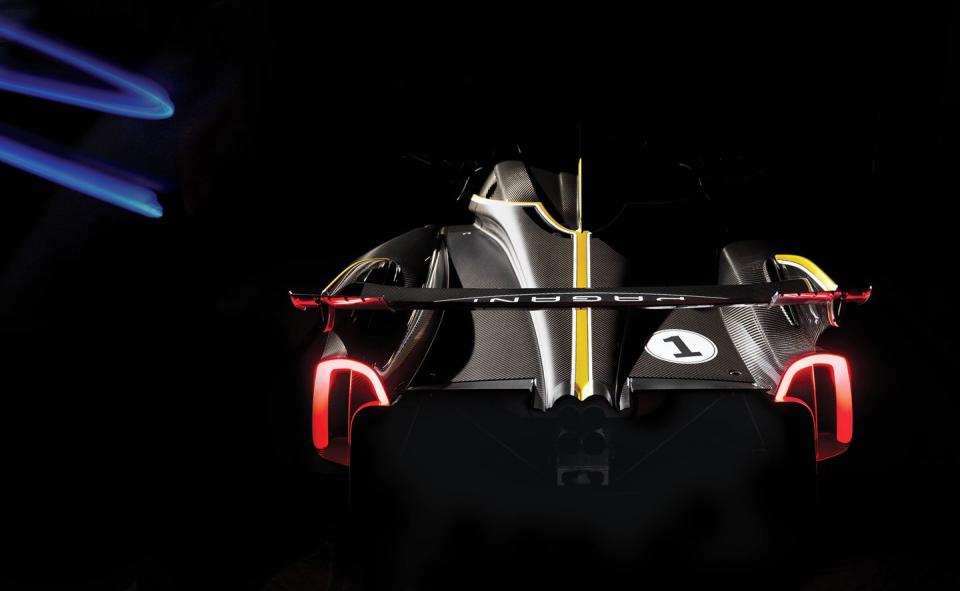

The Huayra R won’t be as quick as other billionaire track toys like the Aston Martin Valkyrie AMR Pro or (probably) Gordon Murray Automotive’s T.50S Niki Lauda. But I would bet my heavily mortgaged house that nothing will sound better. Nothing could. The R’s hand-built naturally aspirated V-12 exhales through standard unsilenced pipes, although buyers will also get a more muted system for those unsporting racetracks that limit noise levels. With the free-flowing system, the R yowls and howls and even gets close to ululating as it downshifts. It really does sound almost exactly like Ferrari’s 1995 F1 car, the V-12-powered 412 T2.

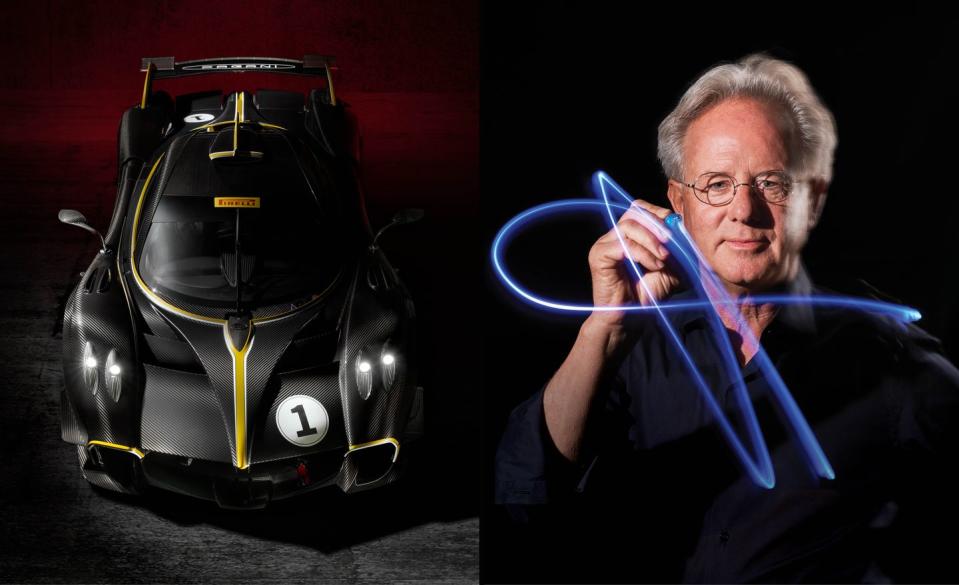

Pagani admits that Ferrari’s FXX program is the inspiration for the Huayra R, with owners of the 30 cars set to be invited to exclusive driving events on premier race circuits. Despite its name and basic form, the Huayra R shares essentially nothing with its street-legal sibling—the door mirrors are the only common components. The R has a new ultralight carbon structure built to satisfy FIA safety standards, a load-bearing engine created in Germany by HWA (an AMG bit that Daimler didn’t acquire), and a motorsport-spec Hewland six-speed dog-ring transmission. The 6.0-liter V-12 makes 850 hp, revs to 9000 rpm, and has to motivate just 2314 pounds of dry mass. The composite body can also generate up to 2200 pounds of downforce.

Despite having statistics more potent than many actual race cars, the Huayra R has necessarily been designed for amateur drivers. The probability is slight that a person will have both the $2.7 million necessary to buy one (before any bespoke options) and topflight racing experience. Even so, the Huayra R looks and feels like an exceptionally well-finished race car, especially once you’re strapped into the cockpit, grasping the yoke steering wheel and looking through the canopy windscreen.

Starting off is easy thanks to anti-stall and an electrically operated clutch, but hopes of making any serious attempt on Vallelunga’s lap record are stymied by the need to follow a Huayra Roadster BC acting as a pace car. In most cars, keeping up with a 791-hp road-legal Pagani would be a challenge, but in the slick-shod Huayra R, the car in front might as well be a Miata. I’m soon trying to find ways to create gaps big enough to experience scant seconds of the R’s full savage acceleration and the growing effect of aerodynamic downforce in faster turns. Cornering grip is predictably huge, but unlike many real race cars, the Pagani doesn’t feel as if it will bite when the limits are reached or even breached. Well before the end of my stint, I’m turning down the variable traction control to increase the sensation of the rear end squirming and sliding under power.

Does it make sense? Rationally, zero. You could have multiple seasons of racing in the Ferrari Challenge or the Lamborghini Super Trofeo for much less money, and you’d get to say you were an actual racing driver. But, like Pagani’s other cars, the Huayra R has off-the-scale emotional appeal. It is the work of a maestro, born from an obsession for detail. You can feel Horacio Pagani’s pride in every fiber of the wheeled artwork he creates. His signature is simply the crowning touch.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos