How the pandemic made Instacart “essential”

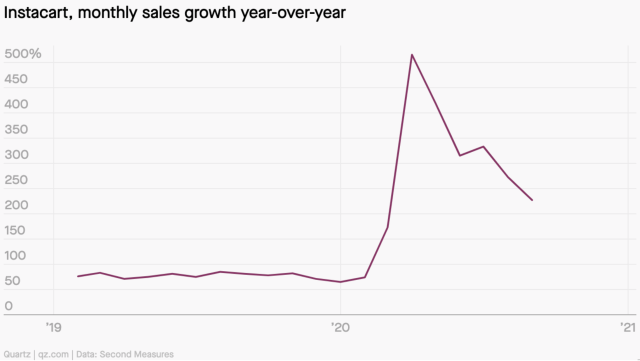

If you’ve been inside a grocery store recently, perhaps you noticed a number of people pushing around jam-packed carts while scrolling furiously through their phones. The pandemic is powering growth for grocery-delivery startup Instacart, and many of those shoppers are handpicking groceries for the app rather than their own households.

After reportedly losing $300 million last year, San Francisco-based Instacart turned a profit for the first time in April. In October, a report from investment bank Cowen found that Instacart is the third most popular online US grocery destination, after Walmart and Amazon. The company is expected to go public as early as 2021, at a possible valuation of $30 billion.

The grocery-delivery app—currently valued at $17.8 billion, according to PitchBook—partners with over 500 retailers including Walmart, 7-Eleven, and Sephora, and delivers from 8,000 store locations across the US and Canada. It exists in a saturated space: Gig companies like DoorDash and Uber are also getting into groceries, as are big retailers like Amazon, Walmart, and Target. But there’s also huge opportunity, as Covid-19 drives record levels of demand.

In March, online shopping accounted for almost 7% of all US grocery sales, up from 5% at the end of 2019, according to a Bain report. In the UK, online sales hit 12%, compared with 8% pre-Covid. In France, online sales jumped to 10% from 6%, and in Italy they doubled to 4%. Analysts are expecting at least some portion of that surge to stick around: By 2025, online grocery is expected to hit 22%—or $250 billion—of total US grocery sales.

To contend with demand, Instacart has hired hundreds of thousands of contractors to help it fill orders. It’s also vying for a diverse customer base, making delivery service available to shoppers on food stamps and launching a phone service to add 60,000 seniors to its platform.

But that expansion is also exacerbating tensions around worker compensation, workplace protections, and lack of hazard pay. Now Instacart must keep up with short-term demand while laying the groundwork for the online-grocery long game.

By the digits

41 minutes: Length of the average trip to the grocery store.

2%: The average grocery store’s profit margin.

$225 million: Instacart’s latest funding round.

750,000: Active Instacart shoppers.

$35 billion: Grocery sales Instacart says it’s on track to process this year.

85%: US households that can get grocery orders filled through Instacart.

$155: How much the average customer spent on Instacart the week of Sept. 21, according to research firm Second Measures, up 20% year-over-year.

39%: Share of millennial respondents to a 2019 Instacart/Harris poll who said they would rather give up their phones for a month than be responsible for cooking a Thanksgiving dinner.

Remember when

If Instacart ever needs a cautionary tale about growing too quickly, it can refer to Webvan, considered one of the most notorious dot-com flops. The online grocery startup filed for bankruptcy in 2001 after burning through $800 million in just three years, and became a poster child for the perils of too-quick expansion, too-little management expertise, and too much money spent building out a proprietary infrastructure.

Instacart’s origin story

You’ve heard this one before: In 2010, Amazon logistics engineer Apoorva Mehta felt unfulfilled by his day job. So he quit and moved to San Francisco to start his own company.

After considering 20 different ideas—including a social network for lawyers—Mehta zeroed in on the pain points of grocery shopping. In the spring of 2012, the first prototype of Instacart was born: Mehta placed his first order, picked up his own items, and delivered them to himself. He later landed an investment from Y Combinator after using the app to send a partner there a six-pack of beer.

Since those early days—when Mehta would Uber orders around San Francisco himself—Instacart has expanded to 5,500 cities across the US and Canada, and has raised $2.4 billion in funding from investors including Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia Capital, and Kleiner Perkins.

Labor tensions at Instacart

From tipping policies to worker classification, Instacart has long faced labor backlash. In 2015, following lawsuits from independent contractors who said they were being treated like employees, the company gave in-store shoppers the option of becoming part-time employees with limited benefits. In 2018, Instacart hosted a “Shopper Experience Council” at its San Francisco headquarters, where Mehta said that it has “real debt with its shoppers.”

But labor tensions continued to stew: In 2019, Instacart workers alleged the company offset wages with tips from customers. And during the pandemic, which has given added exposure to how employers treat different classes of workers, Instacart shoppers have pushed for better pay and protections.

Then came Proposition 22. Earlier this month, California voters approved a ballot initiative that essentially exempts gig companies like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart from needing to classify their workers as employees, a distinction that would require them to pay into benefits like workers’ compensation and health insurance. The companies together spent over $200 million pushing Prop 22—it was the most expensive ballot initiative in California history—and are now laying the groundwork for similar initiatives in other states.

What’s in your cart?

Perhaps the best window into the strange world of Instacart is r/InstacartShoppers, a Reddit thread where shoppers share tips, ask questions, and talk shop about gigs. Highlights include:

Theories on the tipping habits of different generations.

Intel on what kinds of orders no Instacart shopper will accept.

The best (and worst) of customer behavior.

Keep reading:

Does being made “essential” give gig workers the upper hand?

What gig companies’ narrative about “job flexibility” leaves out

An SEC proposal would make it possible for gig workers to get equity

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

Scientists are worried a second wave of Covid-19 infections is starting in Kenya and South Africa

India’s next mega-airport is inviting flyers to “design your own airport”

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos