Parnelli Jones, 1933-2024

One of the toughest, fastest, most determined and versatile drivers to ever grace motorsport has left us, aged 90. Rufus Parnell Jones, born in Texarkana, Ark., in 1933, died of natural causes on June 4, in Torrance, Calif., the city where he had lived since he was seven years old.

How significant a figure was the man we knew as Parnelli Jones? The late, great Robin Miller said it best: U.S. motorsport’s Mount Rushmore would feature A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney and Parnelli. And there’s little point in disputing that because he was right.

Parnelli signified speed. Just as overenthusiastic drivers in the U.K. in the ’60s would be asked by admonishing police officers, “Who do you think you are? Stirling Moss?” so traffic cops on this side of the Atlantic would compare a speeding driver unfavorably with Parnelli Jones. And inevitably, there came the fateful day when the man himself was stopped, and he was able to reply, “As a matter of fact, I am Parnelli Jones.” That would become the title of his excellent biography with journalist Bones Bourcier.

Yet the “Jones” part became superfluous: he was among those elite sports stars – Nuvolari, Pele, Kobe, Shaq, Fangio – who required only one name for everyone to know the subject of the conversation. There was only one Parnelli.

How he attained this unusual (unique?) name is tortuous, but has its roots in the not uncommon desire for a young driver to fudge his age. Jones’ mother had named him Rufus Parnell after a local judge whom she respected, but the name Rufus Jones would have been rare enough to ring a bell with potential visitors to his local track in Gardena, just five miles from Torrance. It would therefore have been easy for officials to trace his age and learn he was 17 – a year younger than the legal age to compete. What to do? A high school friend, Billy Calder, came up with the solution. He had nicknamed him “Parnellie,” fusing his middle name with the first name of Nellie, a girl who was rather keen on our handsome hero, and one day Billy painted “Parnellie” on the door of Jones’s 1934 Ford jalopy. The final “e” was eventually dropped; the remainder stuck. Billy couldn’t have imagined that his friend’s memorable new alias would go on to become an iconic name.

Parnelli got his start in local bullrings and never lost his enthusiasm, or success, on short tracks.

In jalopies, Jones was a badass, scoring around 100 wins across SoCal, and he was more than ready to progress to NASCAR’s Pacific Coast Late Model Series, where he accrued 15 wins. In fact, West Coast stockers alone would eventually bring him 22 triumphs, and this form brought him to the attention of team owner Vel Miletich in 1956. Together they decided to enter NASCAR Cup at Darlington Raceway in 1958, and despite starting 44th, Parnelli managed to lead a couple of laps before suffering engine failure.

Progressing to IMCA sprint cars for 1959, Jones made an impression with fifth in the championship despite missing several rounds in the first half of the season. The aggression required in such powerful open-wheelers suited his style, although in truth, he could be quick in anything, either by taming a car’s manners to follow his will or by adapting his inputs to suit the car. The net result was that he won the USAC Midwest Sprint Car title in 1960, and followed it up with USAC’s National title in ’61 and ’62. In fact, he was simply brilliant in sprint cars, eventually ending his career with 25 Feature wins to go with his 25 triumphs in midgets.

By then, he had joined the Indy (Champ) car fray and in his ninth race at the top level, at California State Fairgrounds in Sacramento in 1960, he snagged a runner-up finish. But that was just the gravy: it was his simultaneous Midwest Sprint Car crown that had caught the eye of promoter J.C. Agajanian, who became desperate to get this phenomenon on the grid at Indy. Aggie’s judgment and anticipation of greatness proved faultless.

Only a year earlier, Jim Hurtubise had – as a rookie – set the Brickyard’s new one-lap benchmark of 149.601mph during a four-lap qualifying run that made him the fastest in the field. (Unfortunately he had achieved this on the fourth day of time trials, so his run made him eligible only for 23rd on the grid.) “Herk” then used this platform like a latter-day John the Baptist, warning anyone who would listen that an even quicker driver would be among them soon, namely, his sprint car rival Parnelli Jones. Hurtubise, like Agajanian, was spot on: P.J. became the man to beat at IMS.

On his Indy 500 debut in ’61 with the Agajanian Willard Battery Watson-Offy, Jones qualified fifth and led 27 laps (figures precisely matched by Fernando Alonso on his debut some 56 years later, incidentally), but he lost a cylinder in the second half of the race, and a piece of metal struck him above the left eye. The blood then ran down from the cut and filled his left goggle, so that every few laps he’d have to empty it. Still, he kept on, crossing the line in 12th. He had done (more than) enough to earn himself Rookie of the Year honors, albeit shared with Bobby Marshman. There would soon be a runner-up finish at fearsome Langhorne, a fifth at Syracuse, another runner-up finish at Sacramento and finally a breakthrough win in Phoenix.

The following year promised much, and a second-place finish at Trenton to open the ’62 Champ Car season seemed like just a warm-up. Come the Month of May, Jones ran a 150.729mph lap, an Indy single-lap record, and when all four of his laps produced an average of 150.370, he not only had a record, he also had pole – a full 1mph faster than even former winner Rodger Ward. Having led laps 1-59 and laps 65-125, however, Jones then lost his brakes, making his pit stops a scuffling, shuffling nightmare, so he would eventually come home a frustrated seventh.

Elsewhere on the IndyCar trail, Jones was always a force to be reckoned with and further runner-up finishes at Milwaukee, Langhorne and Springfield, a third at Langhorne’s second race, top fives at Trenton, Sacramento and Phoenix and a victory at Indianapolis’s State Fairground gave him third in the championship.

After showing what he could do with a bit less bad luck in his first two years at Indy, Jones and Ol’ Calhoun got the job done in 1963.

Thanks to an unhealthy dose of DNFs, in ’63 he would slip to fourth in points, but that almost didn’t matter: he clinched Indy. Having started from pole position again, this time alongside his buddy Hurtubise and another great, Don Branson, Jones led 167 laps but found on race pace his nearest opposition came from the rear-engined Lotus of Indy car rookie but Formula 1 yardstick Jimmy Clark. As has become Indy legend, Jones’ car, Ol’ Calhoun, started weeping oil – no worse than others, insisted his defenders – due to a crack in the tank, and by the time Lotus founder Colin Chapman had alerted authorities, the car’s oil level had dropped beneath the split. Thus no black flag was deemed necessary, and Clark skittered home some half a minute in arrears. One who spun and crashed on oil was Eddie Sachs and, assuming it was Jones’s doing, confronted him at the post-race banquet… where he received a bunch of knuckles for his trouble. Clark, by contrast, kept his peace, congratulated his rival, grinned charmingly and vowed to return.

Parnelli would soon accept that running a roadster against the rear-engined “funny cars” at any paved track was a short-term policy. He found success elsewhere, taking the 1963 stock car class of the Pikes Peak Hillclimb, a feat he would repeat the following year, but post-Indy, Jones failed to lead another Indy car lap in ’63. At Milwaukee, he had seen Clark score the first win for a rear-engined Indy car (as opposed to Bernd Rosemeyer’s Vanderbilt Cup victory at Long Island for a Grand Prix-spec Auto Union in 1937). And at the Brickyard the following year, Parnelli qualified “only” fourth for the 500, behind Clark, Marshman and Ward, all pedaling funny cars. When Clark’s Lotus retired with tire trouble that broke the rear suspension, Jones looked like he might win back-to-back Indy 500s. But Ol’ Calhoun caught fire as it left the pits and the blaze was serious enough that Jones had to bail while the car was still rolling.

Two races later, Jones tasted the future at Milwaukee, driving a Team Lotus entry to pole and leading 195 of the 200 laps, emulating Clark’s domination there a year earlier. Three races after that, Jones was at it again, holding everyone’s feet to the flames around Trenton. He liked the Lotus and excelled in it.

Parnelli expanded his reach into stock and sports cars in the mid-’60s, including a brilliant stint in Bud Moore’s Trans Am Mustangs.

In fact, in 1964 he proved he had adapted to rear-engined cars, period, having won the prestigious Los Angeles Times-backed 200-mile sports car race around the twists of Riverside in a Cooper T61-Ford against the likes of Jack Brabham, Ken Miles and Bruce McLaren that same year. But he had kept his hand in with sedans, wheeling a Mercury to six wins and that year’s USAC Stock Car Championship. His road course flair and his wins for Lotus even led to an invitation from Colin Chapman to join Clark in F1. Jones, as canny as he was fast, knew the second Lotus ride was a poisoned chalice, knew Indy car offered more money than F1, and said he wasn’t interested.

At all, as it turns out. Parnelli was pretty much done with open-wheel racing at the age of 31, and his full-time Indy car career ended when the ’64 Indy car season did – or rather, a few laps before that. He had been crushing the opposition in the season finale in Phoenix when a puking fuel injector sent oil onto his rear tires, spinning him hard into the wall.

Jones was as tough as they come but this shunt prompted a career rethink and he acknowledged that team ownership was increasingly dominating his thoughts. In ’65 he entered just five Indy car races – second behind Clark at Indy, first again at Milwaukee. In ’66, it was Indy only – he qualified a Shrike in fourth but was out before half-distance due to wheel bearing failure.

But the Indy near miss that has lodged in everyone’s memory and that broke the hearts of both Jones and STP’s ebullient racing director Andy Granatelli came in ’67. Jones, coaxed out of retirement to drive the STP Paxton Turbine car, dominated the race – 171 laps led! – only for a six-dollar bearing to fail less than eight miles from the checkered flag. Winning NASCAR’s 500-mile race at Riverside was no consolation for this.

So he wasn’t going to put his neck on the line again as an Indy car driver: he had found the love of his life, Judy, they were keen to become parents, and the odds in this perilous era were always stacked against drivers who drove to the nth degree. But he couldn’t rid his system of the racing bug, and so Jones’ racing repertoire expanded laterally. No one who saw him wheel a Bud Moore-run Ford Mustang in the Trans Am series will forget the never-say-die attitude he exhibited, almost from corner to corner. There was no drivers’ championship awarded until a couple years later, but his five wins from 11 races in 1970 ensured Ford was well ahead of the opposition in the manufacturers’ standings, and made Parnelli unofficial title winner.

Perhaps the most unlikely fascination for Jones — notwithstanding his interest in driving hard whenever, wherever, and understanding the mechanicals of his cars — was in off-road racing. Never one to merely dabble, Parnelli threw himself wholeheartedly into the Ford Bronco project, and came out smiling: two Baja 1000 and two Baja 500 wins between 1970 and ’73 were the result.

Switching to team ownership proved just as successful for Jones, who with partner Miletich and driver Al Unser conquered Indy back to back in 1970 and ’71.

By then, he was also proving to be a very successful team owner in his first love, IndyCar, having formed a team with his old business partner, Miletich. He hired Indy 500-winning race engineer George Bignotti to wrench, and the budding Al Unser to drive. This combo scored five wins in 1969, then dominated the ’70 season with Bignotti’s modified Lola — the Colt — used on all paved tracks. Unser scored 10 wins that year including Indy, and earned a runaway championship. The following year, Unser again had Indy among his five wins, while ever consistent teammate Joe Leonard captured the title for VPJ.

For ’72, Jones made the unusual move of forming a “super team,” retaining Leonard and Unser while adding Andretti. The result was anything but super, according to Unser, who hated the weird and not-so-wonderful VPJ-1 design from Maurice Philippe, who had initially replaced the rear wing with a pair of dihedral devices mounted mid-ship. It was one of those occasions where thinking outside the box made one realize why the box existed.

Once converted to more standard form, the car gained a lot of speed, and Leonard would actually retain his championship, taking three wins and a clutch of other top-five finishes, when neither of his superstar teammates Unser and Andretti seemed able to buy even a finish. They had to be content with earning the USAC National Dirt Car championship for the team in 1973 and ’74 respectively.

VPJ Racing briefly ventured into Formula 1 with a single car for Andretti, from the tail end of ’74 to the start of ’76, but Philippe’s VPJ-4 design showed a clear resemblance to the by-now six-year-old Lotus 72, which he had also penned. While in 1975 Andretti scored a fourth place finish at the Swedish Grand Prix, a fifth place in France and third in Silverstone’s non-championship International Trophy, the car never showed any inclination of allowing Mario to regularly threaten Ferrari and McLaren; only talent and chutzpah enabled him to tackle the Brabhams, Tyrrells and Shadows. Having been unable to find a replacement for Firestone as the car’s primary sponsor over the previous 18 months, Jones and Miletich grew disillusioned with this branch of the sport and departed F1 just a couple of races into the ’76 season.

Despite the best efforts of Mario Andretti, the VPJ F1 project was a disappointment. Motorsport Images

Thanks to the efforts of Unser, Danny Ongais and some neat designs and updates from the impressive youngster John Barnard, Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing stayed prominent through the mid- to late ’70s. But struggles with the early turbocharged Cosworth DFX, built at VPJ’s facility in Torrance (no one could accuse Parnelli of lacking ambition!), meant the gaps between wins seemed to mainly fill with DNFs – not conducive to winning championships. For example, in 1978 driving the sole Parnelli, Ongais, the Flyin’ Hawaiian, scored eight poles and five wins… yet finished the year a mere eighth in points. Still, VPJ had made a big enough impression on the good days that Cosworth itself would take over the project.

In the background, and occasionally the foreground, VPJ also earned wins in Formula 5000, drag racing and SCORE off-road racing. Parnelli’s business had been an extension of him — far-reaching, forward thinking and successful — but now it was time to move on to other business opportunities. He formed a partnership with Foyt late in the 1978 season — A.J. was eager to get his mitts on a VPJ-6 — and gradually the deal morphed into a takeover by Super Tex. Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing as an independent racing entity was done after 53 Indy car wins and 47 poles.

As a driver, Parnelli’s talent continued infrequently but apparently undiminished. As late as 1991 he was winning the Pro Celebrity Race at Long Beach (for the third time), and into the 21st century he was defining new track limits at Laguna Seca during historic events. He made finding the outer threshold of a race car’s dynamics look oh so easy as he drove races oh so hard. And fast. It was a pleasure to watch his son PJ find success in IMSA sports cars in the 1990s driving in a very similar manner for one of the other American greats, Gurney. His other son, Page, looked as if he, too, was on his way to stardom before suffering a life-threatening shunt in a USAC sprint car at Eldora in 1994.

Parnelli was a true enthusiast to the very end, commending another versatile maestro, Kyle Larson, for his excellent performance at the Speedway in the run-up to last week’s Indy 500. If he could have, Parnelli would have been there and driving the pace car, as he did back in 1994 and ’98. On both those occasions, it seemed reasonable to wonder if he might end up providing the field of 33 a chance to warm up their tires by setting the fastest pace laps in Indy history. Behind any steering wheel, he just couldn’t stop being that Parnelli Jones.

Jones was a remarkable driver even in an era chock-full of them. He became an Indy 500 legend by not only winning the 1963 edition, but also by leading a 492 laps in just seven starts. In short, when he was on track, he was the benchmark, and anyone who beat him could dine out on it forever. But few could, fewer did.

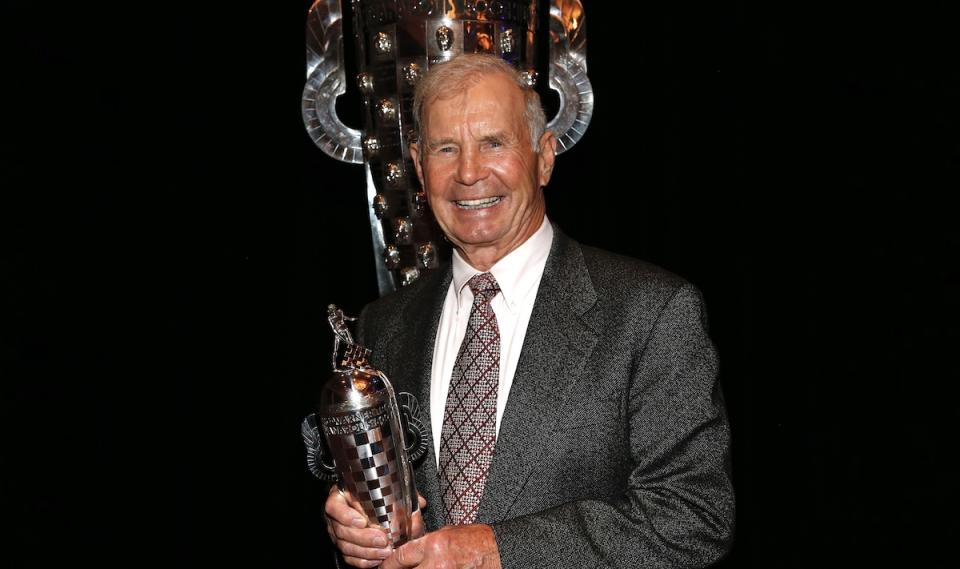

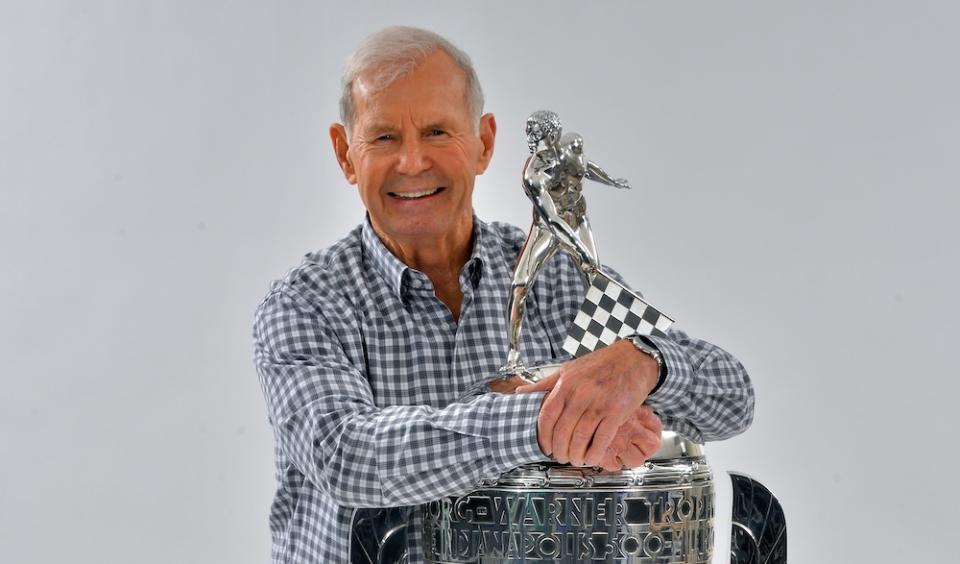

When BorgWarner started its practice of creating retrospective “Baby Borgs” for Indy 500 victors who missed out on the keepsake (the tradition of a miniature Borg-Warner Trophy for the winner didn’t begin until 1988), it was only right that Parnelli was the first recipient, in 2013. Heck, his status was (and remains) such that on the wall of his office, he had personal letters from three U.S. presidents.

50 years later, Parnelli finally collected a Baby Borg.

Also on the wall was a picture of he and Foyt, which both had signed and shared. Neither man was going to inflate the other’s ego, but like champion boxers after a grueling fight, there was respect. “To P.J.,” wrote Foyt, “You were hard to beat.” Jones’s response: “To Foyt, you are one of the best.”

Jones had also framed and displayed a printed comment by former rival and later employee Andretti. Inevitably, Mario had summed it up perfectly. The statement reads: “As far as I’m concerned, Parnelli Jones was the greatest driver of his era. Whether he was racing sprint cars, Indy cars, sports cars, Can-Am or stock cars, he exhibited a flair that was all his own. He had aggressiveness but also a finesse that no one else possessed. And he won with everything he put his hands on, including off-road.

“I certainly looked up to him, and I won my first championship in 1965 only because Parnelli retired after Indy that year. And for that, I say thank you. Had he continued racing, PJ would have amassed a record that would have been the envy of everyone.

“So if you want to describe a total winner, there you have it — Parnelli Jones.”

Jones had the respect of his peers not just because of his skills, however: he was also big-hearted and self-confident enough to encourage talent, even while knowing said driver could become a thorn in his side somewhere up the road. At Pikes Peak in 1962, Bobby Unser and Parnelli “officially” met and bonded for the first time, and Bobby, already a five-time winner of the contest, showed his new buddy “the fast way up my mountain.” Jones appreciated that, and 10 months later at Indianapolis, when the shoestring team with whom Unser passed his 500 rookie test ran out of money for tires, Parnelli was instrumental in getting Bobby in Granatelli’s Novi for the race. Thus from this Jones-nurtured seedling another legendary career grew. And, sure enough, the combo of Bobby Unser and Dan Gurney’s Eagles would go on to beat the VPJ team to race wins and championships.

As he made his way across the spectrum of American racing, Parnelli remained open to learning and to help out new talents – even though doing so helped make them new rivals.

Parnelli’s generosity would also bite him in a different way decades later, when Robin Miller and BorgWarner PR guru Steve Shunck were dining with the pair of them. Bobby — “The Preacher” as Parnelli dubbed him — would be making multiple, haphazard points that could last a couple of courses, to the entertainment but glaze-eyed disbelief of the others. Finally, the mad monologue would be interrupted by Miller, who would look across at an amused Parnelli and yell, “You’re the one responsible for this man! It’s all your fault, Rufus!”

It’s painful to realize that such happy, bench-racing, edifying and trash-talking meet-ups won’t happen again, and that Parnelli, like Bobby, Big Al and Miller, has been proven mortal. This author had long been convinced otherwise. On the few occasions I met Parnelli, it felt as if I should be standing to attention and saluting, despite his friendly demeanor, much mellowed by age. In fact, it was only in our last couple of conversations (sadly, a few years ago) that I felt comfortable to address him by his first name; until then it had been “Mr. Jones” or “Sir.” That was just the kind of mystique he possessed and aura he projected, quite unwittingly, and though Parnelli has now gone the way of all flesh, his legend is immortal.

To Parnelli’s wife Judy, sons PJ and Page, and grandchildren Jagger, Jace, Jimmy, Joie, Jet and Moxie, we extend our deepest sympathy. To his friends and rivals and leagues of fans, we stand beside you in mourning a fallen legend.

There was only one Parnelli. There will only ever be one Parnelli.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos