Pato O'Ward, Colton Herta, And Alex Palou Know How Good They Are

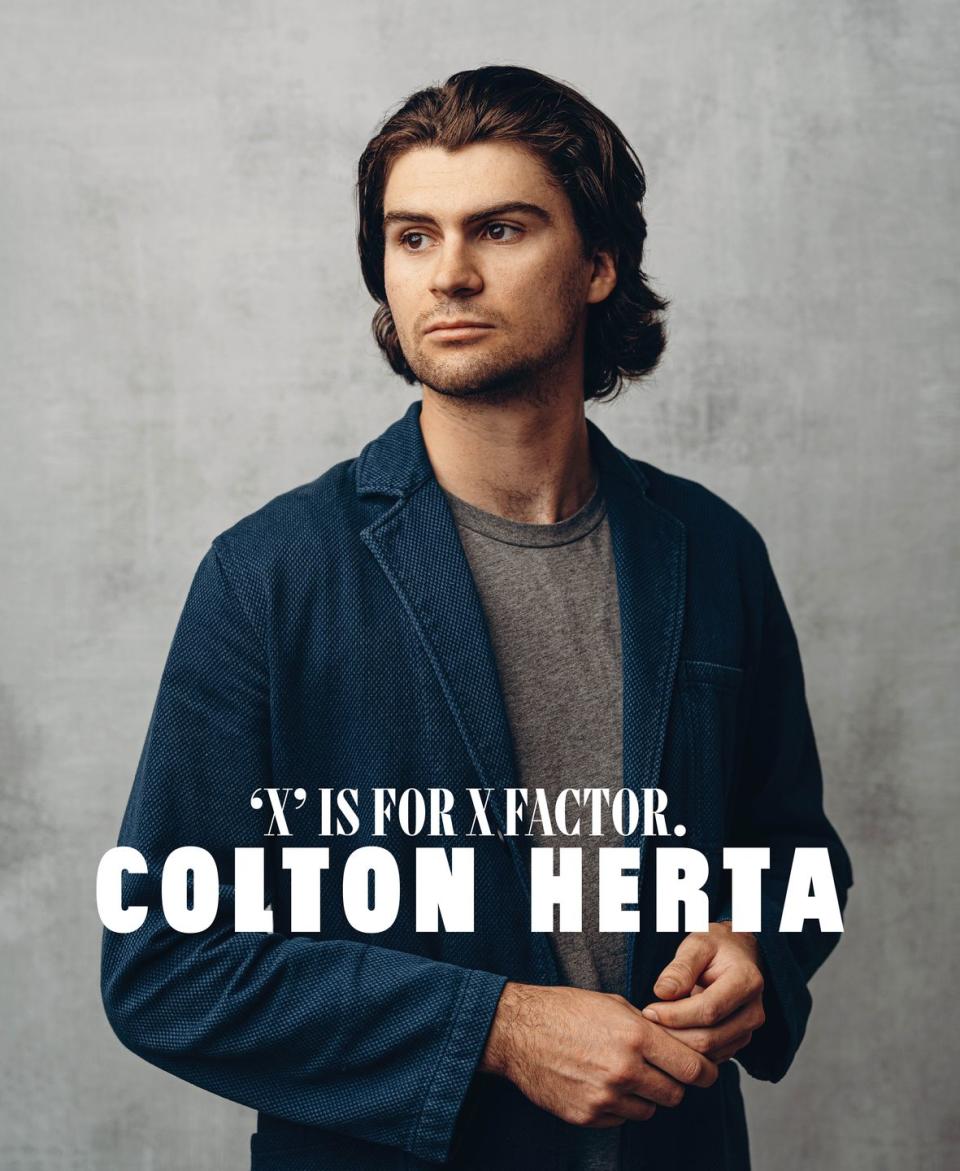

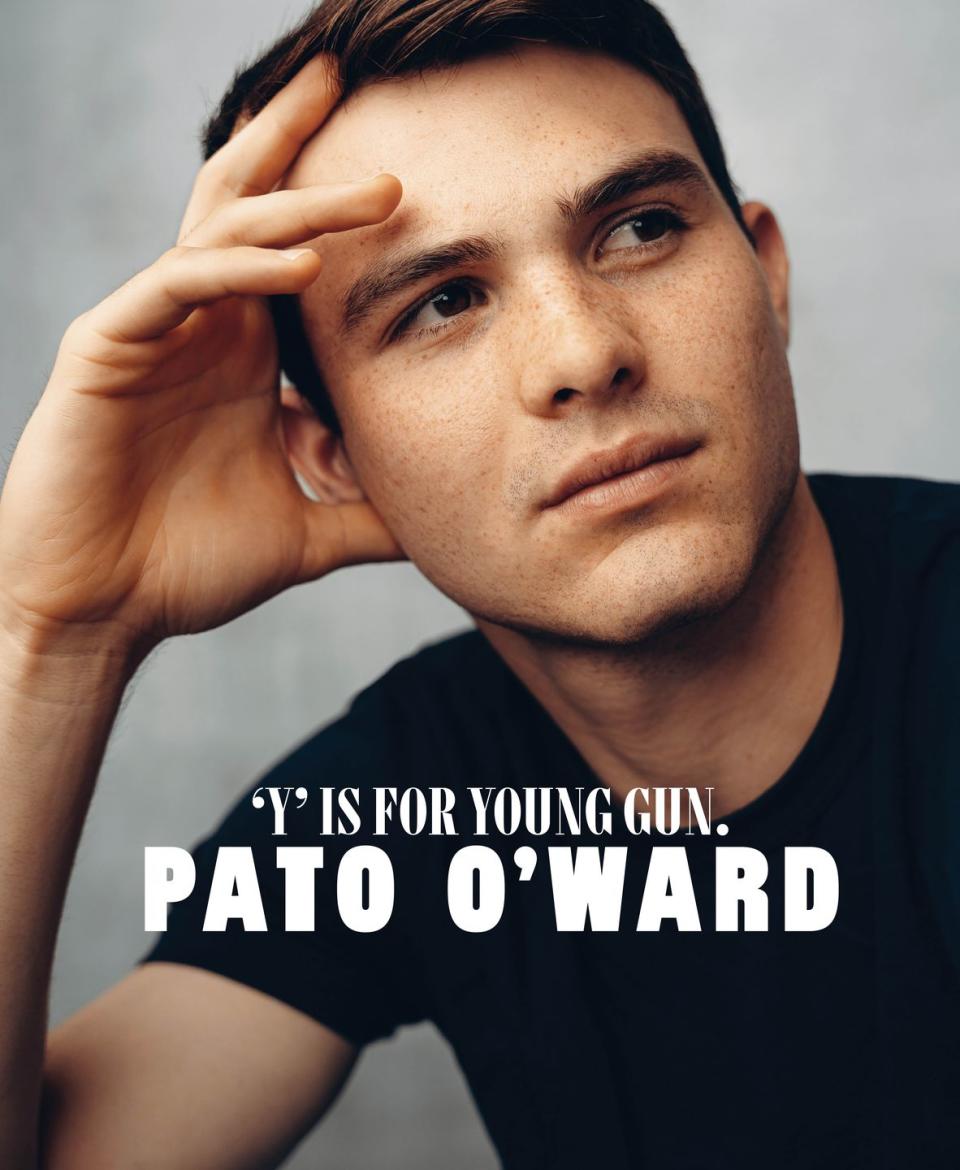

Pato O’Ward and Colton Herta are stars locked in intersecting orbits. O’Ward, a 23-year-old Mexican IndyCar star with an oh-so-Irish name, is on pace for his third top-five finish in the series points in his three seasons of competition. Herta, the 22-year-old Californian son of IndyCar veteran Bryan Herta, has already accomplished that twice. The pair have been teammates three times, tested the same Formula 1 car, and finished one-two in seven separate races of the 2018 Indy Lights season. When O’Ward won the LMP2 class at the 24 Hours of Daytona, Herta was his co-driver who made the winning pass.

This story originally appeared in Volume 13 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

From 2018 to 2020, they were the dual rising faces of IndyCar. Then Alex Palou showed up.

Palou is a 25-year-old Spaniard—ancient on the warped timeline teams use to assess racing drivers—who celebrates race wins with fried chicken. While Herta and O’Ward sailed through the North American development series, Palou struggled on Europe’s Formula 1 ladder. After four seasons in Europe, he moved to Japan and blossomed in the 2019 Super Formula Championship. That led to his 2020 rookie IndyCar season with Dale Coyne Racing. When Chip Ganassi Racing’s Felix Rosenqvist moved to join O’Ward at Arrow McLaren SP, Ganassi hired Palou.

While O’Ward and Herta starred on the way to multiple wins and top-five championship finishes in 2021, Palou went one step further. He won his debut with Ganassi at Barber, finished second at the Indianapolis 500, and took two more wins. By the end of the year, he was in complete control. O’Ward came into the finale at Long Beach with an outside shot at the championship but was spun on the opening lap and never recovered. Palou became an IndyCar champion in just his second season.

O’Ward is unmistakable. Watch an IndyCar race on TV, and odds are there will be an onboard shot of the No. 5 McLaren when O’Ward struggles to keep the car on track while passing top-10 cars. On street circuits, road courses, and ovals alike, O’Ward stands out as the driver working harder than everyone else. In other categories of racing, this is speed being scrubbed away. In IndyCar, where a heavier chassis with little downforce and a strange balance races on a variety of bumpy tracks, O’Ward sees his style as a necessity.

“I think the style of IndyCar fits me well,” O’Ward explains. “You’ve got to manhandle the race cars to extract the lap time out of them... It’s a safe race car and a race car that can handle insane amounts of abuse in terms of track, driver, cars touching other cars. If an F1 car were to touch the rear tire of another car, the front suspension would just explode. In IndyCar, you can sideways bump into someone and have no issues. The thing is a tank, and I think that’s different to every other single-seater in the world.”

Competitors recognize O’Ward’s style too. He guessed what Herta and Palou would say about him—that his style was aggressive. Herta praised O’Ward’s steering prowess, noting that they both have particularly fast hands and that O’Ward uses his to balance any car. For Palou, what stands out is how O’Ward channels that success into massive gains on track.

“If he starts really far in the back, he tries to overtake five in a corner. And normally, he makes it work.”

The final restart of the second 2021 Detroit street race with nine laps to go was vintage O’Ward, that is, if anything a 23-year-old does can be considered vintage. He picked off drivers to move to fourth. When he noticed both Herta and Palou on the same preferred tire behind the leader on what should have been the slower tire, he kicked in the aggression.

“When we restarted, I got by Dixie [Scott Dixon], then I got by [Graham] Rahal, and as soon as I got by Rahal, I was right up onto Palou,” O’Ward enthuses. “They weren’t doing anything, they were just staying where they were, and I was like, ‘What are they doing?’ So I’m kind of just like, ‘Okay, I’m going to start sending it,’ and let’s see where it works out. I passed Palou on the outside. Then I got to Herta. I was quicker than Herta, passed him, and as soon as I got to Josef [Newgarden], I was like, ‘This is mine.’”

O’Ward won the final race in Detroit that weekend. With controlled aggression and creativity as a passer that rivals Magic Johnson’s, he thrives in these situations.

In the right conditions, Herta seems the fastest man alive. He has nine poles in three and a half seasons, but that only hints at how much faster he can be on the right weekends. In races like the last two at Laguna Seca, he has been untouchable. Herta describes the style that leads to this speed as a willingness to overstep what the car can do.

“I feel like I’m one of those guys who has to go over the limit to find it,” he says. “Washing up a little bit, maybe running a little bit wide in some corners, just to find that limit, exceed it, and then dive back into shape.”

Herta has quick hands, which he also displays drumming for his band, the Zibs. On track, his ability to find and react to limits were the key to an instant-classic drive at the Indianapolis road course in the rain earlier this season. He went onto dry tires on a damp track a lap earlier than the field and spent the next lap saving multiple bouts of snap oversteer. Then he caught race leader O’Ward on colder tires with just one chance to press his advantage. Pushing beyond that limit to overtake, Herta seemingly lost the car, an oversteer moment so pronounced that it looked more like Formula Drift than IndyCar. He responded by moving his hands off the wheel’s narrow grips to rotate to full lock. Then he flicked the wheel back. It was the save of the century.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos