What’s a plenum and why are they on fire?

Let’s delve into a phenomenon that’s nothing new in turbocharged forms of motor racing, but took center stage on Saturday in qualifying for the Indianapolis 500 when multiple Chevrolet-powered entries experienced plenum fires at the most inopportune times during their four-lap runs.

First, what’s a plenum?

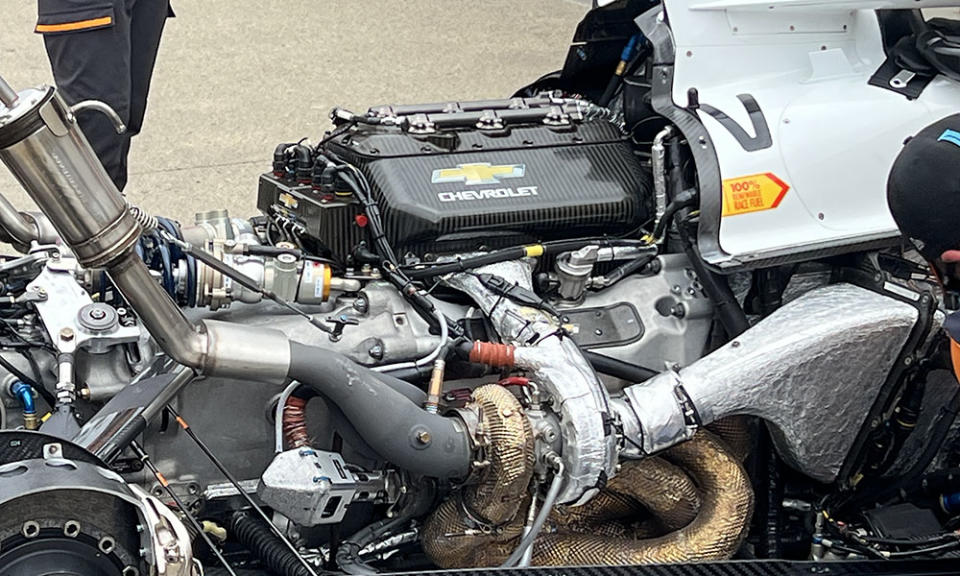

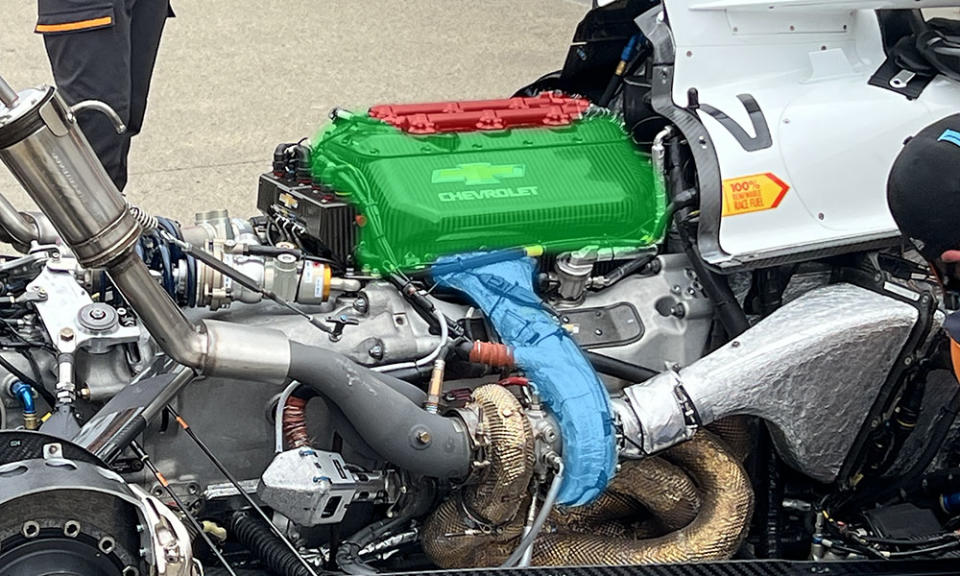

It’s an enclosed airbox that sits atop the 2.2-liter twin-turbo V6 IndyCar motors made by Chevy and Honda, and in IndyCar, it’s made from carbon fiber.

What purpose does the plenum serve?

It’s the meeting and mixing place (below, in green) for the highly compressed air sent into the sides of the plenum (in blue) from the turbos and the fuel sprayed downward from atop the plenum by the injectors (in red) to swirl and be inhaled by the engine.

The plenum encases and seals around the engine’s intake trumpets that feed the mix of air and fuel into the cylinder heads, which is then compressed by the piston, ignited by the spark plugs, and exploded/burned to make horsepower.

Marshall Pruett photo

How is a plenum different from a regular airbox on non-turbo NASCAR Cup engines and Cadillac IMSA GTP motors?

Those big naturally-aspirated V8s use scoops to funnel air into the intake trumpets in an open manner; since they don’t use turbos, there’s no need to place a sealed plenum over the air intakes to hold that pressurized air. With the purpose of turbocharging centered on stuffing compressed air into the engine, a sealed plenum ensures there are no pressure leaks.

IndyCar road and street course races, plus qualifying for the Indy 500, uses 1.5 bar of pressure to make big power. On a non-turbo engine, it works at 1.0 bar, which is the normal atmospheric pressure we walk around in every day.

With turbocharging, the air is drawn into the cold side of the turbos and forced under high pressure — known as forced induction –into the engine at something greater than atmospheric pressure.

That compressed air, which is dense, and contains more oxygen than what’s fed to a non-turbo engine, needs to remain compressed on its way into the motor, and that’s what the sealed plenum provides.

So what causes a plenum fire?

With the swirling blend of compressed air and fuel being continually packed into the plenum to be drawn down into the six combustion chambers, that ignitable mixture is at risk of being lit and burned up before it gets into the cylinders if an inlet valve is left open for a fraction of a second while there’s flame left in a cylinder.

The inlet valves open to let the air and fuel mixture into the cylinders to be further compressed and sparked, and when everything is working well, the inlet valves close, and then the explosion happens in the cylinders, and the burned remnants are disposed of when the exhaust valves open and the expended mixture is fired through the exhausts and sent out through the back of the car.

But in the event of the flame sneaking back up through an inlet valve, all of that combustible mixture in the plenum gets lit and burned before it gets a chance to reach the combustion chamber.

It’s believed that at high boost, the extra pressure being applied to the inlet valves from the compressed mix in the plenum is making it possible for the brief unsealing of the valves to then let fire escape when it shouldn’t.

So why are we having a bunch of plenum fires at Indy on qualifying runs?

There are a few reasons, with the first being the high boost pressure that’s being used of 1.5 bar this weekend. We’ve also seen plenum fires at road and street course races; Pato O’Ward was on the way to victory in his Arrow McLaren Chevy at St. Petersburg in 2023 when a late plenum fire caused his car to stumble and let former Chip Ganassi Racing driver Marcus Ericsson sweep by and win with his Honda.

With the Chevys at high boost, the fires — more accurately, the millisecond or two where an inlet valve stays open to let flames fire upwards into the plenum — here at Indy have been triggered when drivers are shifting while the engines are at their 12,000 rpm limit and the rev limiter is engaged. Something in the interaction between the electronic rev limiter cutting in to prevent the Chevy motors from going over 12,000 rpm while shifting is the cause of the “engine events.”

And while we’ve seen plenum fires happen on upshifts, the common denominator with most we’ve seen this weekend have come while on qualifying simulations or proper qualifying runs while downshifting from top gear — sixth gear — to fifth.

What does it feel like for the drivers when it happens?

“The engine stops,” said Team Penske’s Will Power, who experienced a plenum fire during Sunday’s Fast 12 practice session. “It kills your speed massively. At first, I thought the engine was blowing up, but it wasn’t.”

It feels that way because the continuous flow of air and fuel into the combustion chamber has been temporarily halted; there’s no mix to explode and make power and that means the engine is momentarily starved of what it needs to keep accelerating. Think of it like a bad, single hiccup.

Once the hiccup clears, breathing goes back to normal, but when you’re flying at nearly 240mph, any brief interruption in acceleration is alarming and will certainly hurt your qualifying speed.

What about Honda?

It’s worth noting that while Honda has far fewer plenum fires with its engines at 1.5 bar, they do happen on occasion with their motors. But the frequency has been much higher within the Chevy camp. It’s hard to say why since we don’t know what both manufacturers are doing mechanically within their engines and with engine calibrations, but there’s something that’s different enough to make this a Chevy story instead of a Chevy and Honda saga.

And finally, what can Chevy or their drivers do to solve the problem?

Nothing that we know of on the Chevy side. GM racing boss Jim Campbell said on Saturday evening that Team Chevy engine technicians would be working overnight to try and devise engine calibrations that would be loaded into the engine control units to use Sunday morning in the aforementioned Fast 12 practice session, and while there were many options to try, it happened again with Penske and Power.

For the drivers, once they get up to speed on their warmup laps and shift into top gear, they need to stay there. It means they might lose a bit of ultimate speed where quick downshifts to fifth would keep the revs and speed up, but with the ever-present threat and clear downside of triggering a plenum fire, holding the car in sixth is the one obvious remedy for the problem.

Again, this is by no means something new for Chevy, but it has become a serious concern as it looks to break Honda’s four-year pole position streak at the Indy 500. Once qualifying is over and the engines are reverted to low boost, plenum fires should be all but forgotten on race day.

Let’s talk plenums and fires at the Indy 500. pic.twitter.com/FyNlc9nB8v

— Marshall Pruett (@marshallpruett) May 19, 2024

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos