Porsche 911 GT3 RS and GT4 RS Invert the Line Between Road and Track

While other brands flirt with the racetrack, Porsche has committed to it, building production-based racing cars for the track and street since the beginning. It forged that connection in 1973 with the legendary 2.7 RS, the first 911 to wear the two letters that today signify the ultimate motorsport experience for the road. RS stands for rennsport, which simply means “racing” in German.

This story originally appeared in Volume 19 of Road & Track.

The American adage “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” seems to apply better to Porsche than nearly anything built stateside today, not because the Corvette doesn’t win races—it does. It’s because Porsche will, unlike General Motors, sell you a car that looks and feels very similar to the ones you see covered in grime on the podium after a hard-fought endurance race.

Porsche wants you to believe you are buying a racing car that is legal to drive on the street, while other manufacturers want to sell you a street car that will hold up to occasional playtime on a racetrack. That crucial difference leads us to two of the hottest super–sports cars on the market: the GT3 RS and the GT4 RS.

In motorsport’s early years, the line between sports cars and race cars was pretty blurry. Racing cars were perfectly legal to drive on the street, and production sports cars went racing on the weekends. Safety considerations like roll cages hadn’t been mandated yet, and slick tires might only be found at a drag strip, so nothing really separated a race car from a street car besides power, weight, and maybe the number of seats.

In the late Fifties and the Sixties, the line became more distinct. However, high-end manufacturers frequently offered their roadgoing cars with motorsport-derived upgrades, such as magnesium knock-off wheels, thin glass, auxiliary driving lights, and aluminum-alloy body-panel options for race-ready sports GTs like the Mercedes 300SL Gullwing and the Ferrari 275 GTB/4. At the same time, full-on racing cars like the Ferrari 250 LM and GTO, the Porsche 550 and RSK, the Ford GT40, and the Mercedes SLR were road legal in most places.

Then Fiat took over Ferrari’s road-car operations and effectively stopped building street-legal race cars, except for small-batch specials such as the 288 GTO and the F40. Mercedes backed away from homologated sports cars after Gullwing production ended in 1957, focusing instead on luxury models. BMW’s 3.0 CSL “Batmobile” is an icon today but was a newcomer to motorsport in the Seventies, and it would take another 15 years to solidify the M brand as “the Ultimate Driving Machine” on the street and track. The Americans sold street-legal variants of their Trans Am icons until emissions regulations forced compression reductions that hobbled performance.

But Porsche stayed the course. While the brand’s 959 forecast a coming era of comfortable, daily-drivable supercars, its RS models kept their edge. Vehicles like the 996 GT3 RS offered unfiltered performance, while the 991 GT2 RS was an experts-only Nürburgring slayer. An RS designation from Porsche means something very special, as is the case with today’s GT3 RS and GT4 RS.

I have to pinch myself after saying that I’m the only person at Road & Track who’s driven both.

These are the most extreme, track-focused variants of the 911 and Cayman, respectively. Porsche has made calculated trade-offs to produce two of the sharpest, most responsive, best-performing cars across the entire automotive spectrum. With an RS product, Porsche focuses on changes that result in lower lap times (the Spyder RS excepted), typically at the Nürburgring, although a good Ring time will translate to a good lap time almost anywhere.

It’s not just lap times, though—RS cars are overachievers no matter the game: The GT3 RS gets to 60 mph in 2.7 seconds and runs the quarter-mile in 10.9, according to our frenemies at Car and Driver. Drag racing is not a priority for Porsche, yet this car returns the best acceleration for the least amount of horsepower in the entire industry.

A side effect of factory performance on the track is a pure, raw driving experience on the street. Porsche’s RS products feature one of the last high-strung, naturally aspirated engines on the market, a 4.0-liter flat-six that spins to 9000 rpm and makes 493 or 518 hp, depending on application. At a live sports-car race, the sound of a Cup car or a 911 RSR is unmistakable—a piercing soprano howl that singes your eardrums and leaves a permanent scar on your brain. It’s smooth and silky, not rumbling and guttural like the V-8s from AMG, Chevy, or Ford, or unmemorable like the turbocharged motors from everyone else.

The engine in the current crop of RS products isn’t closely related to that engine—it is that engine. This isn’t just a branding game where Porsche sells street cars with fender flares, stickers, and big wings and wants you to have a Pavlovian response, confusing the street car with a race car. You can literally watch the MA2.75 flat-six race on the weekend and drive home from that race in your GT3 with the same engine.

Another thing we say in America is “If you can’t fix it, feature it.” This is a great mantra for entrepreneurs struggling with shortcomings in their products. For engineers, particularly those selling the drama of motorsport, it offers a unique opportunity to build a car in which the owner can gearhead vice-signal.

Back in the day, you’d have to give up some comfort and convenience to drive a very high-performance car. It was an unfortunate trade-off but something you could spin into a positive:

The driving position is awful, but it’s the fastest car in the world.

It overheats in traffic, but listen to the sound that engine makes.

If you don’t rev it high enough every time you drive it, the plugs will get fouled, and you’ll ruin it.

It has to have the engine removed for its annual service, which costs $5000.

Technology and the demands of modern customers have resulted in an enormous market for supercars that can be used as daily drivers. There is no sacrifice to using a Ferrari 488 or a McLaren as a daily driver in 2023. Call me when you’re dailying an early Diablo.

With an RS product, Porsche has used engineering limitations to give clients something to brag about—they can vice-signal about what they must put up with in order to tap into the purest driving experience around.

For example, the GT4 RS features the same 4.0-liter engine as the GT3 RS. It makes more power than the six-cylinder from lesser Caymans, but it’s also physically bigger and taller, so the airbox sits up higher. Solution? Put the airbox in the cabin and run the intakes directly behind the passengers’ heads. At very high revs, such as what you’d see on a track or a mountain road, this setup produces one of the most obscenely sublime sounds you’ve ever heard. It is a true showstopper, an incredible aural experience worth all the money. However, at more pedestrian speeds and lower revs, this configuration produces a boomy resonance that even a gearhead would not want to live with every day.

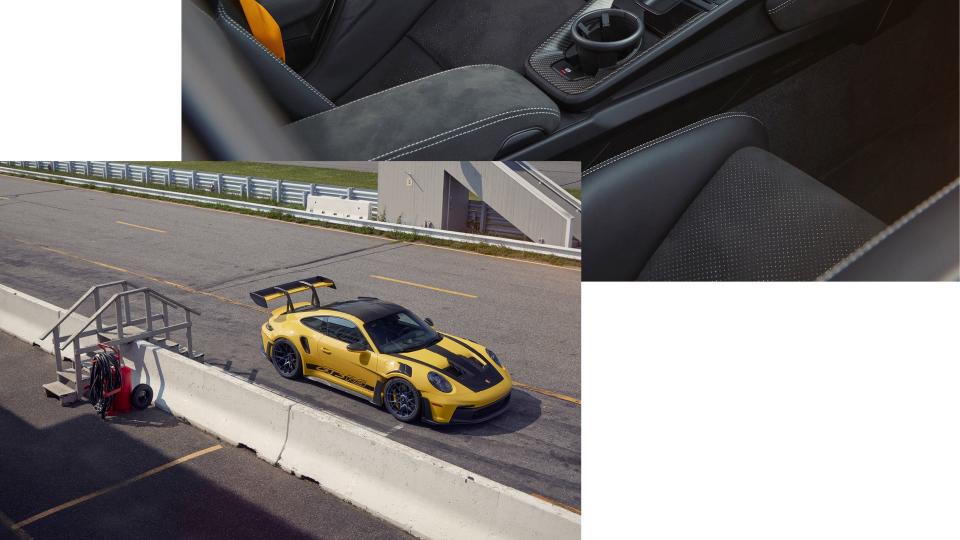

In the GT3 RS, engineers wanted to produce maximum cooling and downforce at the front for extreme levels of grip. To accomplish this, in the center they mounted a large pass-through radiator with an extractor hood lid, as in the RSR race car. Other 911s use smaller radiators mounted on the lower air dam and the sides. The GT3 RS runs cool, even in July in Dubai, while making tons of front grip. The trade-off? That ultracapable radiator is where the trunk was. Though the GT3 RS is big for a two-seater, you’ll have to explain to your friend or spouse that you can’t take anything with you because there’s nowhere to put it. There’s space behind the seats, but the fixed-back carbon buckets don’t lean forward for access to it.

The irony? Customers prefer the inconvenience. When I mentioned to Andy Preuninger, Porsche’s head of GT cars, how annoying it is to have a GT3 RS with no trunk, he responded, “The customers who buy our RS product wanted something more hardcore going from the previous generation to this one. They wanted the race-car technology in there, even if it meant giving up some usability.”

That race-car technology isn’t tamed one bit by incorporation into a street car. Thanks to the rules and regulations governing fairness with their respective racing series, the new GT3 RS and GT4 RS, when shod with slick tires, can lap many tracks faster than their non-street-legal counterparts. These cars haven’t blurred the line between street and track. They’ve inverted it.

A Symphony of Suck

The internal-combustion Boxster goes out with a resounding fanfare.

The 718 Boxster Spyder RS is the first Porsche RS in memory without a specific lap time in its crosshairs. Porsche lopped the roof off a GT4 RS and cut its suspension’s spring rate roughly in half but kept the spectacular 493-horse, 9000-rpm flat-six and 3200-pound-ish curb weight. At the foot of Germany’s Swabian Alps, where densely wooded hillocks unfurl into valleys of wheat, barley, and corn, a red-on-carbon Spyder RS unleashes its fury on the open road.

In Porsche parlance, Spyder is a riff on the Italian “spider.” That means a manual-folding fabric thimble stretched atop this Boxster’s cabin like Borat’s swimsuit, just big enough to cover a pair of... passengers. People will lodge complaints about this finicky cover.

With the top fumbled into its hold below the rear clamshell, I point the Spyder RS down hundreds of miles of tidy German two-lanes. Here, the Boxster’s ride feels firm but never flinty. Unlike the GT4 RS, the Spyder never hurts. That lowered spring rate pairs to exceptionally well-calibrated dampers, resulting in a Boxster that has enough compliance for potholes and also feints into hairpins with only a whiff of roll and all the eagerness of a terrier.

As its RS lineage grew, Porsche chased more with each new model. The rear wings spread broader, the engines revved higher, and the cars became good, real good. But at some point during the past decade, RS cars embraced “more” until it hurt. Now tiptoeing a modern RS down an imperfect back road feels like walking a screaming unicorn along Main Street—everyone stares, and you might return home with an oozing hole in your chest. With the GT4 RS able to please hardcore fans, Porsche was free to tune some on-road compliance into the Spyder RS.

But the company made no compromises with the engine’s intake note.

Just behind the driver’s and passenger’s outboard shoulders sit air inlets feeding the naturally aspirated 4.0-liter engine’s appetite for cubic miles of atmosphere. Below 4000 rpm, a classic Porsche flat-six clatter fills the air, and if you stab at the throttle, there’s an almighty whoosh, like a whale sucking air through a grate. From 4000 to 7000 on the tach, an intake resonance reverberates in your chest. It gives way to a hollering, metallic wail from 7000 to 8000. And those last 1000 rpm before the Spyder RS redlines at 9000, well, there’s simply nothing else on the road like it.

The GT4 RS plays a similar tune with its airbox, but the engine sounds even better in the Spyder RS, somehow less bracing and more textured, even enthralling. As a pure combustion-engined-roadster theater experience, it’s impossible to beat. With a base price of over $160,000 and a heavily optioned car surpassing $200K, it ought to be great.

It’s the first RS car of its kind, but Porsche says this Spyder is also the last new internal-combustion Boxster ever. It’s one helluva send-off, and hopefully, this is not the last Porsche RS with roadgoing ambitions. In that respect, we’ll always take more over less.–Kyle Kinard

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW Hearst Owned

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos