The Problem With Robert Williams

Toward the end of our third interview, Robert Williams gives me some advice about overcoming creative blocks. “Phrase it as a problem,” he says. “For example, ‘The problem with Robert Williams is...’ And then you solve it, and then you have your story.” Cool, cool. He should know about productivity, with more than 300 paintings in his oeuvre, more dirty comics than you could shake a censorship hearing at, and a hot-rod build so confounding that it inspired a whole new scene. The problem with Robert Williams is that wherever he goes, he’s a problem.

This story originally appeared in Volume 23 of Road & Track.

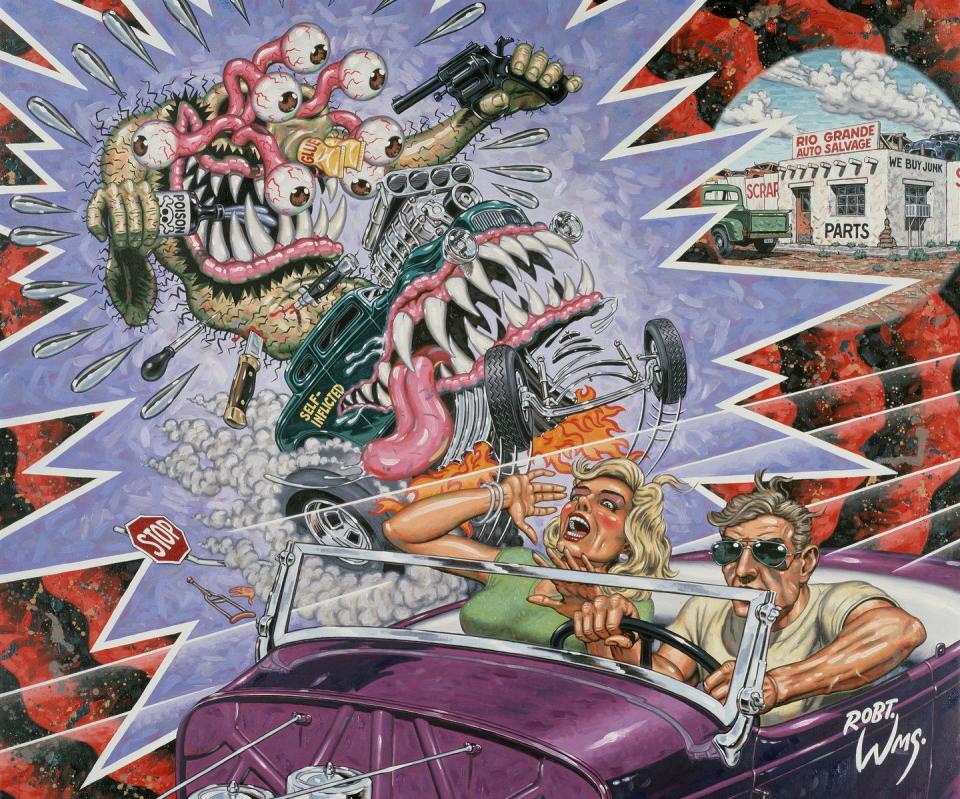

Williams has been a problem for the art world, the field of cartooning, and even the classic-car community, because his work—whether on canvas or on sheetmetal—puts a gloss on the sort of nasty daydreams civilized people deny having and smears muck on the shiny nostalgia that takes the place of real history. He’s hard to get a handle on, his images are full of trapdoors, and critiques of Williams tend to say more about the reviewer than the artist.

In 1963, Williams left Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Los Angeles to stop being a problem and start being an artist. “I had a bohemian streak that was not practical,” Williams says. “I was going no fucking place. My friends were into burglary and drugs, and everything was looking bad, and I wanted to better myself. So I said, ‘I’ll go to L.A., I’ll study art, and I’ll have nothing to do with hot rods or motorcycles.’”

Hot rods and motorcycles, see, were some of Williams’s earliest loves. When he was just a tiny guy in early-Fifties Alabama, his dad used to take him to the racetrack, and he fell hard for the exposed flatheads in the stripped and striped coupes. “I really liked those open-wheel coupes on dirt tracks. It just flipped me out that there were actual cars you could own like that. So I started working on my dad for one of these early Fords, and he got me a five-window coupe. Hold on, I’ll show it to you in this book.” We’re in the library at his ranch-style house in the San Fernando Valley, and he pulls down a copy of The Hot Rod World of Robert Williams. The first page is a torn-and-glued-back-together snapshot showing a 12-year-old in cuffed jeans, barely tall enough to see over the cowl of a sinister-looking ’34 Ford.

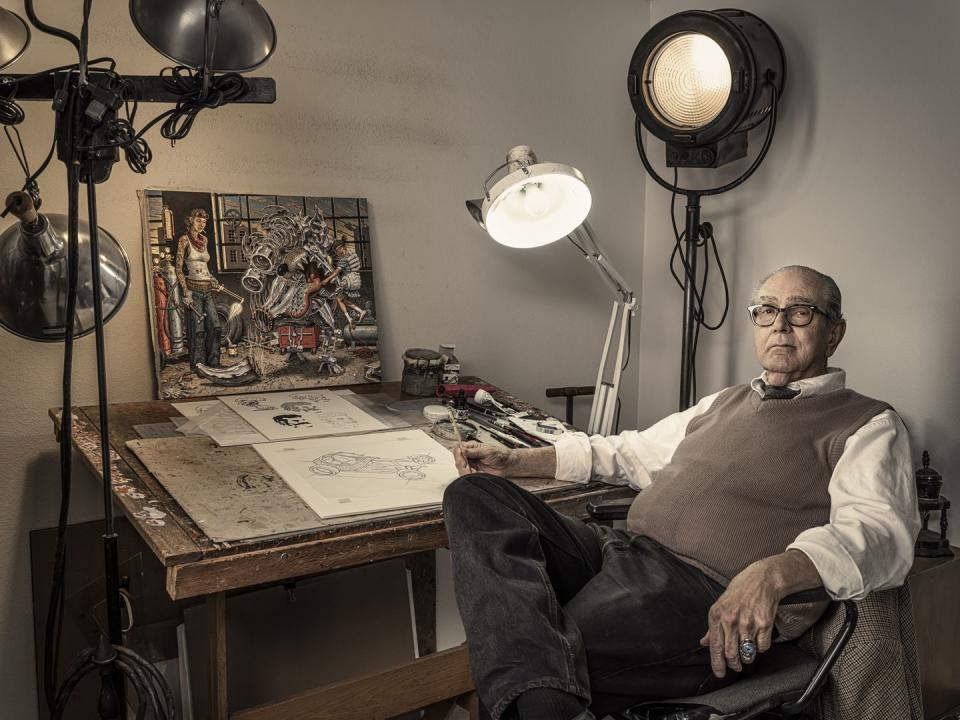

Williams would make a convincing Clyde Barrow. Even now, at 82 years old, he manages to look both stylish and rakish in a tweed sport coat, a tie with a diamond pin, and a sweater-vest that gives him the puffed chest of a perched raptor, a look that’s highlighted by his tendency to cock his head to the side before he speaks. He’s always in the process of leaning forward to nudge the conversation in a new direction. “What do you know about Ford V-8-60 tube axles?” You can please him best by answering, “Not a thing, Bob.” Then he can tell you about them, even if you’d asked about something completely different, like whether he considers himself more of a success in the art world or the car world.

I try again: “Bob, how famous do you feel you are, and for what?” He throws his hands up in aggravation. “What a question! How famous are you?” I tell him I think I’m maybe a 3 on a scale of 1 to 10. He says he can’t answer, that people know him from everything—from his work with the famous car customizer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, from the underground comics scene with R. Crumb, and from his oil paintings, which he reluctantly admits have become somewhat respected in mainstream art circles, after his decades of being the blackest of black sheep.

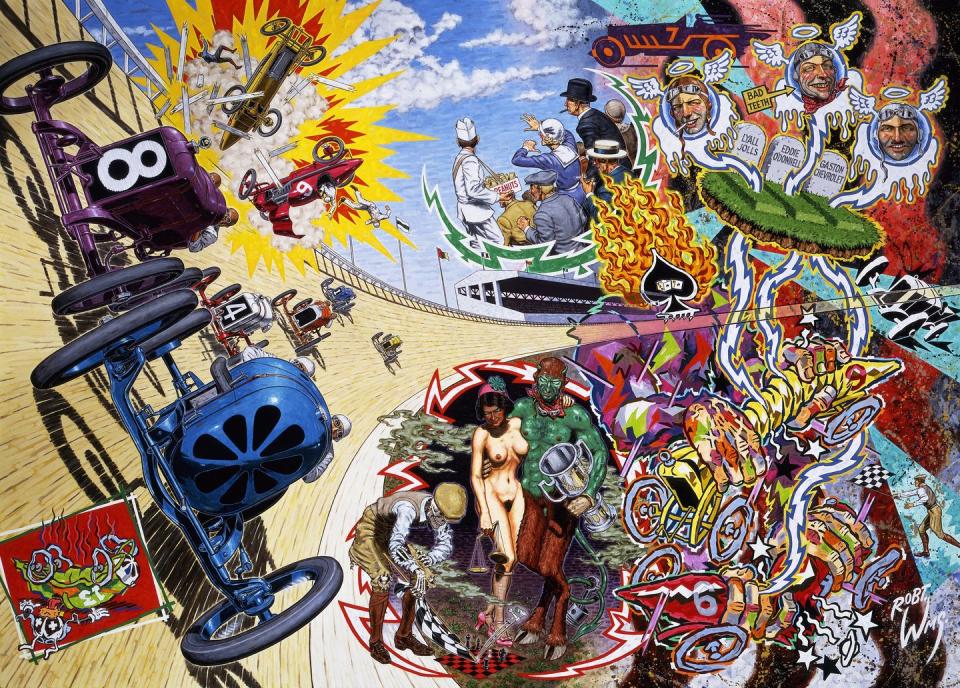

With no help from the man himself, I’m going to say that most people know Williams first from a Guns N’ Roses album cover that became a national news story, so I ask him about that, and he sighs because it’s a story he’s told many times. I did buy him dinner first, so he gives in. “Bands would contact me all the time wanting art for album covers. You know, they’re like garage bands with no money, and I’d let them have an image for $1000. This is in the late Eighties, and I keep getting this. So this band called Guns N’ Roses—they had no big record, they weren’t heard of—they kept calling and calling. They wanted a painting called Appetite for Destruction. They’d seen it on a postcard on Melrose. I told them it was going to cause them a lot of trouble.”

Appetite for Destruction is a startling image, with nudity and quite a bit of implied violence. Williams suggested the band pick something else, but Axl Rose was set on it. The record went to print and indeed caused a lot of trouble, with boycotts and news articles—this being the era of the Parents Music Resource Center hearings about dirty song lyrics and album-cover advisory labels. The furor sure didn’t hurt Guns N’ Roses. Or Williams, who found himself doing the bulk of interviews defending the work. “I’d have to explain the picture to [reporters] because Guns N’ Roses were totally inarticulate.”

He does the hawk lean. “Let me explain that painting to you. That painting was not meant for the general public.” I expect he’ll say the image is about consumerism or some other common metaphor, but instead he describes the painting’s layout and how he uses the different characters to visually tie it back together. Short version: It’s an experiment in formal composition, and the lurid subject matter is just to get people to stare at it long enough to figure it out. “If you look at it that way, it’s like really a fucking killer painting,” he says. Then he laughs and asks how on earth this story fits in Road & Track. And it doesn’t, not really, but it gives you some sense of how disruptive Williams’s work can be when it leaves the dank environs of head shops and punk galleries and finds its way into Tower Records.

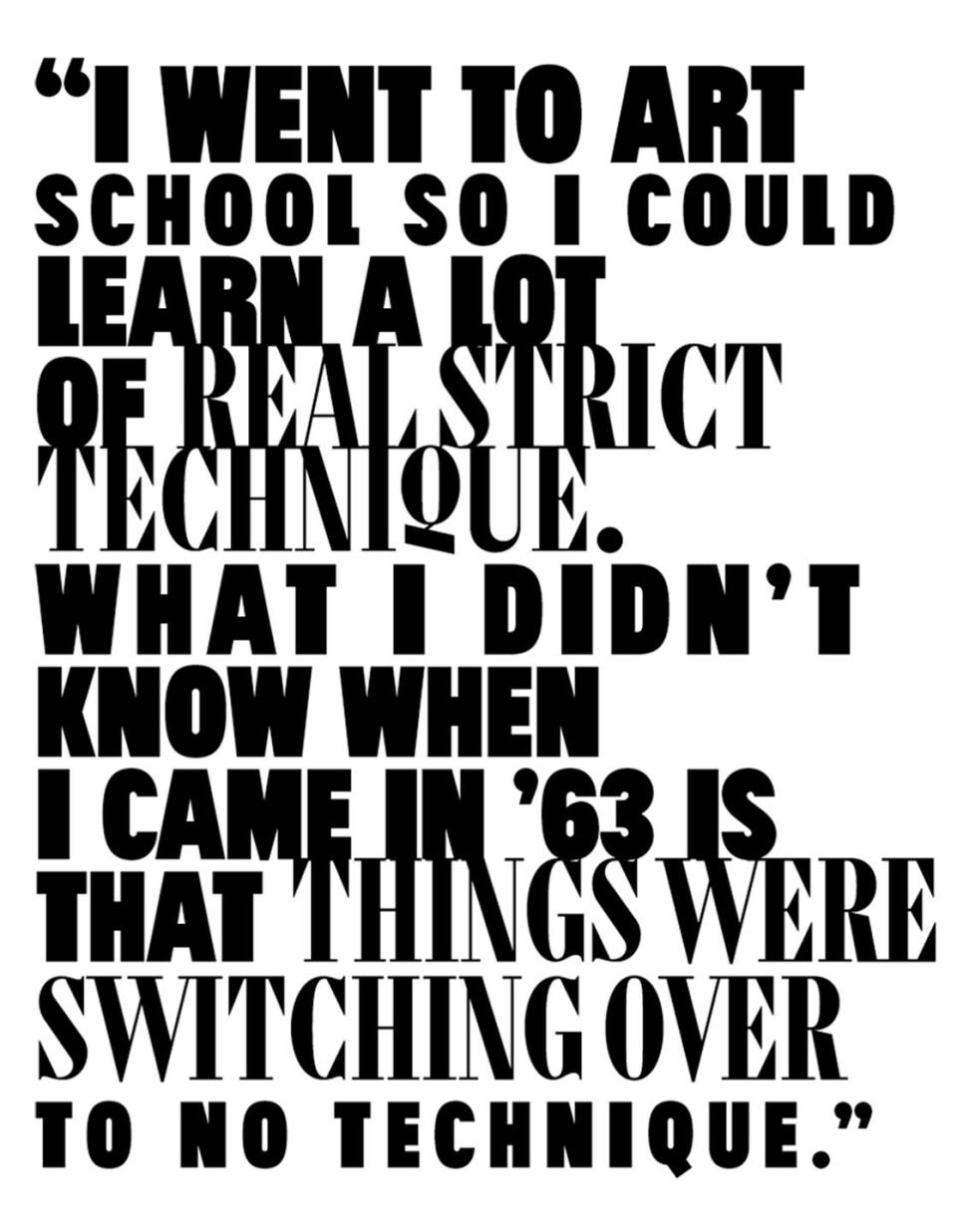

Can you see what a problem Williams is? We’ve barely even talked about cars yet. If you’ll remember, Williams had moved to California to get away from cars, because he was living out Dragstrip Riot back in New Mexico and wanted to be a gallery artist. In L.A., the art world was not what he was expecting. Williams’s interest in formal technique and representative imagery was deeply unfashionable. “I went to art school so I could learn a lot of real strict technique. What I didn’t know when I came in ’63 is that things were switching over to no technique. I made art friends, and they just saw me as no better than an illustrator. There was some resentment about me. I resented them back.” He dropped out of school, worked briefly for a martial-arts magazine called Black Belt, got fired for being too slow, worked as a container designer, got fired for being too weird, and was just about out of ideas when the unemployment office mentioned a gig nobody wanted: art director at a custom-car shop for a guy named Ed Roth.

Roth was the Walt Disney of the custom-car world. His Mickey Mouse was the scabrous Rat Fink. His theme parks were the mirrored and fur-trimmed displays of rod and custom shows. Roth saw romance in motorcycle gangs 40 years before Monster Garage and American Chopper. He could talk to Tom Wolfe in the morning and Von Dutch that afternoon and never notice the difference. He could beat a Hells Angel in a fistfight, win over an IRS accountant, and draw up a best-selling T-shirt all in the same day. Roth saw Williams’s work and told him that had he known he existed, he would’ve hunted him down. It was a good fit for an artist and hot-rodder who occasionally took payment in LSD tabs and rode a unicycle, tripping balls, through Sixties Hollywood.

“I really liked early customs because they had a mystique,” Williams says. “They were low and sleek, and they had this California look of alteration. It was real smooth, and they belonged to another world. Custom cars had a different psyche.” He doesn’t care for muscle cars or Tri-Five Chevys, declaring them nothing more than transportation. “I’m not what you call car people. You know, I’m a hot-rodder, and I like race cars and antique cars. A Nomad to me will always be a fucking station wagon. That’s like having an attraction to a dump truck.” His wife, Suzanne, breaks in to defend dump trucks, but he is on a tear.

“Now, sports cars, that’s something that I purposely never got into, because I’m not interested in developing a hunger for it. Lamborghini or Alfa Romeo or early Ferraris, or things like that, you know, Brough Superior motorcycle, it’s just way out there.” I direct us back to Roth Studios, where he and Suzanne worked until 1970. “There were always hot rods. There were famous movie stars, singers, writers. The Offenhauser brothers were down the street. Mickey Thompson. But when [Roth] got into the biker world, there were some really remarkable examples of human beings, and you’d wonder, ‘What does this guy’s police dossier look like?’ The scale from one end to the other was amazing. There were prostitutes and FBI agents.” Initially, Williams worked on T-shirt and sticker ads that ran in all the car-culture magazines, but Roth became more invested in biker lifestyles, which proved a step too far even for magazines about drag racing and chopped cars. When the mags stopped accepting his advertisements, it became hard to sell enough product to pay the bills, or Williams.

Toward the late Sixties, Roth’s relationship with the Hells Angels had devolved so much that the secretaries were moved into the back of the shop in case of a shootout. By the time Roth closed up shop, the biker drama having done a number on his marriage, mental health, and bank account, Williams was working regularly with Zap Comix, having met several of its other artists thanks to Roth’s influence. Filthy cartoons, as you might imagine, weren’t a big moneymaker, but Williams had been painting all through the Sixties. “About six months before Roth went out of business,” he recalls, “a millionaire named Jim Brucker bought all of Roth’s cars, all of Roth’s artwork, and all my paintings at that time. An enormous amount of money.”

Later, other collectors developed an interest, and even as Williams’s subject matter and style raised hackles, there was always someone willing to take a risk. Much like hot-rod culture itself, Williams went from being an underground shame to a high-dollar investment. Juxtapoz, the underground lowbrow-art magazine he co-founded in 1994, became the country’s best-selling art magazine by 2009. He sighs when I ask whether he misses being counterculture, decades after running with the perverts and punk rockers. “Every artist has to deal with it a little bit, I think,” he says, before changing the subject to his cars, a ’32 roadster and a three-window deuce coupe.

“A hot rod has still got to be an old car,” he says. “A ’32 Ford is a new car for two years, a used car for eight years, and then a hot rod for 50 years. What’s the real personality of that car? There is a romantic provenance that goes all the way back to the owner that comes to you. It has a ghost that comes along with it.”

The build he’s done that most haunts the classic-car scene is his roadster, which kick-started the primered rat-rod revival in the Eighties. Williams purposely never smoothed or painted its rough edges, leaving it in red primer with visible body damage. The look of the car wasn’t what upset people; it was Williams’s declaration that it was finished as is, a philosophical dogleg a lot of builders just couldn’t wrap their heads around. “All the hot-rodders I remember, maybe three-quarters of them never finished their cars, but they had the intention of finishing their cars. They just drove them in the meantime. But there was never anything to say, ‘This is as far as this thing is going to get.’ That was a sin, because then you look like ‘This shit thing is as far as you got,’ but I wanted to get there and call it done. I really liked that look. And that was the first rat rod.”

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW Hearst Owned

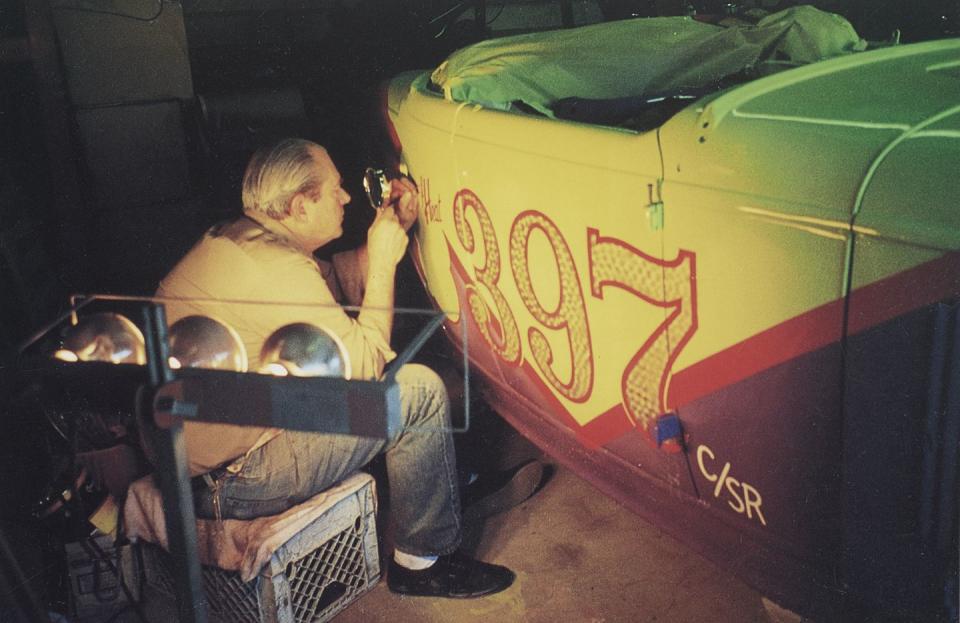

The rat rod confused folks, but the established builders just assumed it was half finished, and the younger builders found it inspiring, so everyone kinda liked it. In 2000, Williams decided to make it worse. “I kept thinking about the race-car paint jobs that fascinated me as a little kid. That redneck indifference to the body-style lines of the car. How the cars would be painted just so they could be seen from the grandstands.”

The finished car, dubbed Prickly Heat, wears a dubious color combo of lavender and American cheese separated by a red stripe the color of a recently pricked finger. More than 20 years since he painted it, the work still raises eyebrows. I tell him it’s sort of horrible, and he grins. “It has a unity of its own that’s exciting to me,” he says. “You know, that’s 24-karat gold on that door hinge.”

I don’t think he’s being willfully hard to handle. In his world, the humid dirt tracks of Alabama merge with the cracked deserts of a cowboy movie, bike gangs lead to Lawrence of Arabia. It connects for him all the ways of being brave and foolish and keeping busy lest the devil find your idle hands (and the shocking things that might happen then). Of course, he also kind of likes to be a problem.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos