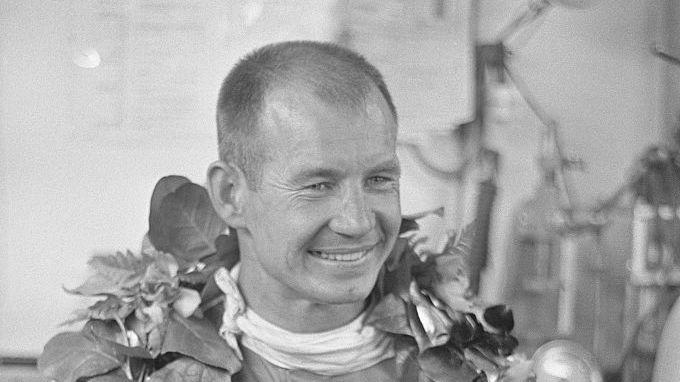

Racing Great, Indy 500 Winner Parnelli Jones Dies at 90

Parnelli Jones, the Southern California racer whose career arced from the earliest days of wheeled competition on long-gone Southern California dirt tracks to the Indy 500 and beyond, has died. He was 90.

The family announced the passing on social media. Son P.J. Jones reported that his father had battled Parkinson's disease.

Jones won in just about everything with four wheels on it: from the original Jalopies that gave him his start on Southern California dirt tracks, to sprint cars, midgets, all manner of NASCAR stock cars, IndyCars both front-engine, rear-engine and turbine, Trans-Am back when the best drivers in the country were driving in it, and two wins in the Baja 1000. As they say, “among others.”

He got by on talent and transparent determination in an era before big money and sponsor-pleasing platitudes took over, when guts and the will to win were all anybody brought to the line. When his driving days were done, he became a team owner with friend and long-time business partner Vel Miletich and won Indy twice with Al Unser driving. Mario Andretti even drove for him in Formula 1 from 1974 to 1976.

But it all started in Southern California, where Jones grew up the son of Arkansas immigrants to the Golden State. Jones was born in Texarkana on August 12, 1933. When the Dust Bowl enveloped the Midwest and wiped out the economy of that state and many others, the Jones family got into their Ford Model T and headed west, along with about a quarter million other Arkies, Oakies and Texies in the same situation.

Jones’ father found work picking fruit at first, before landing a job at a shipyard and setting up the family in Torrance. So Jones didn’t exactly come into racing with a big pile of sponsorship money provided by rich parents. It was that hardscrabble beginning that gave Jones a reputation as the toughest kid in his school, a trait that he would later carry over to the race track. Jones had a reputation as a brawler, both on the track and off. But it wasn’t as deserved as some say, at least the on-track aspect of it.

“People sometimes get it wrong about Parnelli; they talk about him being a bull in a china shop because he was so aggressive, but he was just the smoothest guy to watch,” said Mario Andretti in Jones’ autobiography titled, As a Matter of Fact, I Am Parnelli Jones, written by Jones himself with racing scribe Bones Bourcier. “I’m sure that’s what made him such a good road racer. There was nothing in his background to make you think he’d be good on a road course, but his finesse would allow him to drift a car and do all the other things that work for you no matter where you’re racing.”

As Andretti said, there was nothing in his background… That background was about as simple as any racing career ever.

While in his teens, when Torrance, Calif. still had a lot of wide open, empty fields, Jones and friends began experimenting with cars - and with the laws of physics.

“My friends and I used to buy old cars right out of the junkyard and fixed them up just so they’d run,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Then we’d take ‘em out to the fields and destroy them. I mean we wrecked those cars every way we could. We drove into trees, sideswiped each other, even flipped them by driving off homemade ramps.”

One flip resulted in several barrel rolls and convinced the remarkably uninjured young driver that he never wanted to flip anything again

“Bam, bam, bam, bam. I have no idea how many times that car rolled over, with me rattling around inside. I got banged up a little, but somehow I wasn’t hurt. Never again did I flip another car on purpose.”

If you think about it, though, you could learn a lot about how cars reacted to ridiculous inputs that way, assuming you survived. From those crude beginnings he advanced to more formal racing, or as formal as a class called “Jalopies” could be.

“It was a cheap form of racing,” Jones said at a tribute to him last year at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles.

At the time Carrell Speedway, one city over from Jones’ Torrance hometown, offered all manner of wheeled circle track competition, from Jalopies on up. Young Jones saw them all, even if he didn’t have any money to get in.

“There was a great spot near the restroom where you could jump the fence without being seen…”

What he saw was a young Troy Ruttman, another young racer from humble beginnings, who would go on to be the youngest driver ever to win the Indy 500. It had a huge effect on the slightly younger young kid from Texarkana.

“I didn’t want to just be a race car driver. I wanted to be as good as Troy Ruttman,” Jones wrote in his book.

But how? This was years before karting, before any established entry level racing, before even the Bondurant School of High-Performance Driving.

“The only way you could find out if you had the knack for doing it was by doing it,” he said.

When his cousin’s wife’s ’34 Ford blew its engine, Jones bought it for $25, put a salvaged powerplant in it and raced. His life would never be the same.

Jones started out in the Jalopies – street cars that had had too much street –at tracks like Orange Show Speedway, Culver City Stadium, Long Beach Stadium, Balboa Stadium in San Diego and, of course, Carrell Speedway and Ascot – most of which are long gone. He raced under sanctioning bodies you’ve never heard of like the Southern California Jalopy Association, Stock Jalopy Association, Circle City Racing Association, and the American Jalopy Association. Some races were even televised live on local TV.

After success in Jalopies, he attracted the attention of SoCal Ford dealer and car owner Oscar Maples and Vel Miletich, who was soon to become a Ford dealer. Jones raced stock cars for both of them in NASCAR’s Pacific Coast Late Model Division from 1956 to 1960, occasionally racing in Grand National events. He won 10 PCLMD races and “four or five championships.” Miletich entered Jones in NASCAR 500-milers at Darlington and Daytona.

“Parnelli drove deeper into the corners than anyone, and passed in places no one else could” Miletich once told Bill Libby, author of Parnelli: A Story of Auto Racing.

He went from Jalopies to Sprint Cars and Midgets to stock cars on famous tracks. He raced at Daytona in 1960 for Miletich in the Daytona 500, on the track which had only opened the previous year.

“Daytona… was the fastest track I’d ever run, but it wasn’t the speed that bothered me. It was the air… drafting was a brand-new science…”

And while drafting was one thing, the turbulence was quite another.

“I’d find myself catching some cars, humming right along, and all of a sudden my car would start shaking like a small airplane in a storm… Aerodynamics was not something we’d given much thought to.”

Back in sprint cars, Jones got his first victory in a USAC Sprint Car at Milwaukee, beating such greats as A.J. Foyt and Tony Bettenhausen. By 1961 he was racing at Indy for famed Ascot promoter J.C. Agajanian. His first time out, in 1961, he qualified fifth, not bad, driving the car he called Old Calhoun, a front-engined Watson Offenhauser, to a 12th-place finish. In ’62 he was the first driver ever to qualify over 150 mph, and then lead 194 of 200 laps before the brakes stopped working. In 1963 he was in the lead till the end but was almost black flagged for spewing oil all around the track. Only fervent intervention by Agajanian, who inventively argued with the stewards that there was no more oil to spill, prevented them from black flagging Jones. He won, the second-to-last front-engine roadster to win at Indy.

Jones would come close to winning the 500 again, of course, in one of Andy Granatelli’s radical turbine cars in 1967, when he lead 171 laps before the tranny went out four laps from what would have been his second victory.

After that he turned his considerable driving talents to Trans-Am, where he raced against some of the best drivers in the world, winning the championship in 1970 in a Ford Mustang. Ace fabricator Bill Stroppe soon talked Jones into off-road racing. Jones initially balked at the sport until Stroppe said he guessed maybe Parnelli wasn’t man enough for it. That was all it took. Jones won two Baja 1000s and five Baja 500s.

By that time he and Miletich had formed Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing and he won two more Indy 500s as an owner, with Al Unser driving. By 1974 VPJR was fielding a car in Formula 1 with Mario Andretti behind the wheel. The team scored points in F1 but had to withdraw when Firestone pulled its sponsorship (which sent Andretti to Lotus and his own F1 championship, so it wasn’t all bad).

The whole time Jones and Miletich ran a string of Firestone tire dealerships with the slogan, “Get your Stones from Parnelli Jones.” Many people did.

Jones was not perfect. He came from an era where disagreements with other drivers were settled with a punch in the nose. Parnelli was about the best of the brawlers of his day, so it was usually him getting in the first and often only punch. That settled that, right or wrong.

In retirement, at least as far as every time I saw him, there was none of that. He slid gracefully into the role of elder statesman of racing as easily as he once slid sprint cars around dirt tracks. His sons PJ and Paige, as well as grandson Jagger all followed in Parnelli’s racing shoes with careers of their own.

Just last year, when the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles honored Parnelli with an evening of reminiscing, emcee and interviewer Tommy Kendall asked him how things are now that he’s hung up his helmet.

“First of all, I haven’t hung it up yet,” he said.

The crowd cheered.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos