How Rusty Wallace’s Flying NASCAR Cup Car Saved Countless Lives

In the early 1990s—after upwards of 15 rollovers in that era—NASCAR had a problem: when turned around at speed, its cars and trucks often became airborne.

Driver Rusty Wallace, an NASCAR Hall of Famer, was involved in such crashes at Daytona Beach and Talladega in early 1993.

Wallace's crashes that year, in part, led to development of roof flaps to help keep cars grounded in the event of a crash.

By almost any measure, Rusty Wallace had a tremendous NASCAR career: 36 Cup Series poles and 55 victories, the latter resting 11th on the all-time list. There were 17 top-10 points seasons in 22 tries, including 10 consecutive (1993-2002) for owners Raymond Beadle and Roger Penske. He won the 1989 championship with Beadle and crew chief Barry Dodson and went into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2013.

Impressive? Indeed… but perhaps his greatest contribution—unintentional, to be sure—came from spectacular crashes at Daytona Beach and Talladega in early 1993. There’s no telling how many drivers are alive today because of them.

It happened like this…

In the early 1990s—after upwards of 15 rollovers in that era—NASCAR had a problem: when turned around at speed, its cars and trucks often became airborne. Even at 3,600 pounds, they soared high enough to become entangled in grandstand fencing. Fans were injured when Bobby Allison got into the Talladega fencing in 1987 and Richard Petty went into the fencing at Daytona Beach a year later. Despite those frightening incidents, officials seemed unconcerned until Wallace’s two rollovers in 1993.

First came the season-opening Daytona 500. After contact with Derrike Cope and Michael Waltrip in the waning laps, Wallace spun and elevated, then sailed and rolled and tumbled eight time along the backstretch before landing upright. Footage shows his car clearly above the backstretch wall during one of its cartwheels. Penske’s No. 2 Pontiac was destroyed, but Wallace was uninjured.

Next, about three months later, came the Winston 500 at Talladega. A last-lap nudge from Dale Earnhardt in the trioval turned Wallace’s Pontiac around. Its tail lifted like a small plane taking flight, then began tumbling and rolling and bouncing a half-dozen times while shedding debris for almost 200 yards. Neither Wallace nor any fans were injured, but the unsettling question remained: what if he’d been in the high lane, closer to the grandstands? What if he’d gotten in the fencing as Allison had done six years earlier?

After more airborne crashes that season, officials reacted. When they suggested more engine restrictions to slow cars and keep them grounded, competitors howled. So, NASCAR president Bill France Jr. told Cup Series director Gary Nelson to gather experts and study ways of aerodynamically preventing rollovers. The effort turned an “oh, by the way” concern into a compelling one. France wanted answers, and he wanted them yesterday.

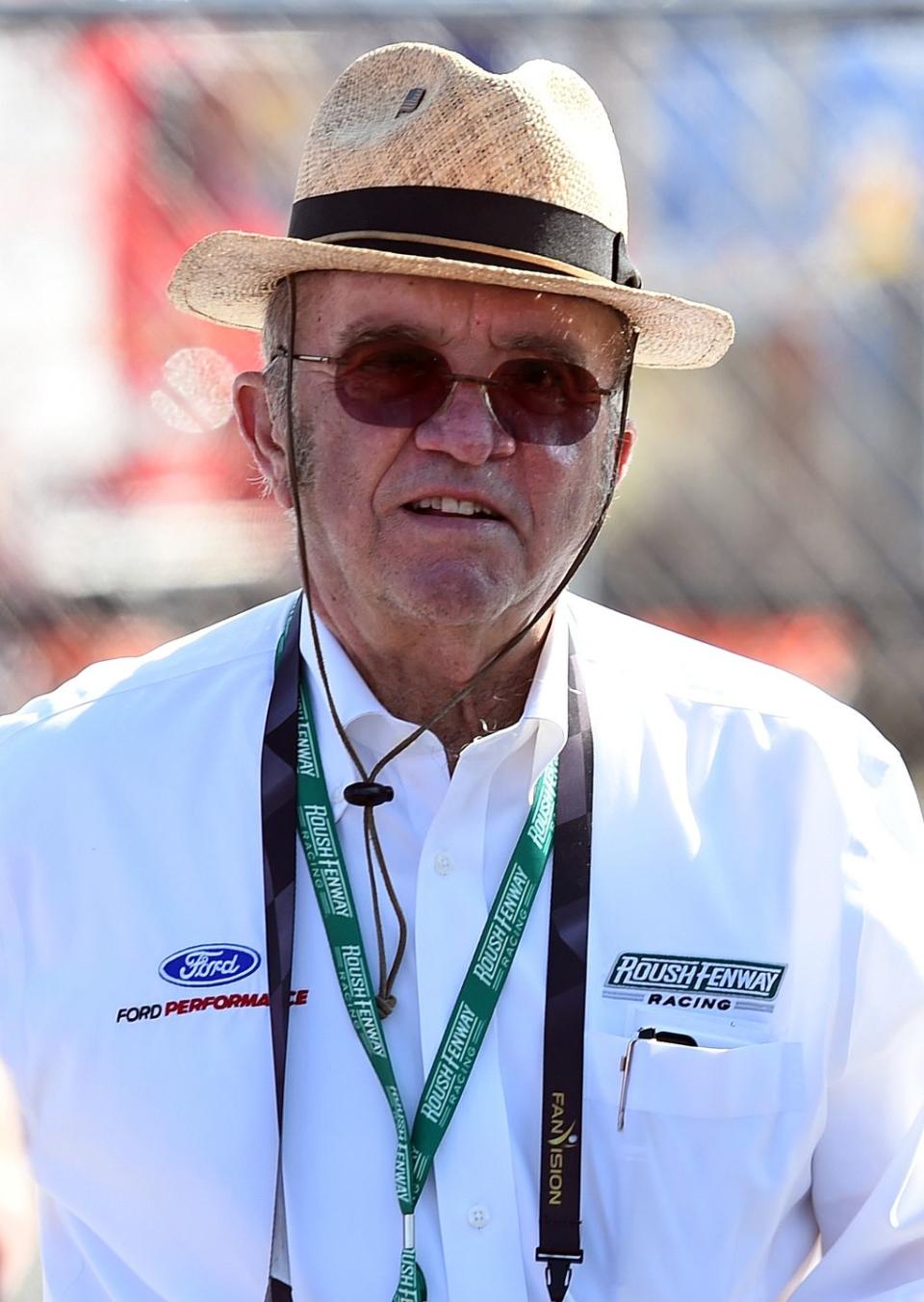

“NASCAR racing as we know it was threatened in the ‘70s and ‘80s because we were having so many rollover accidents,” Hall of Fame owner and aviation enthusiast Jack Roush said in 1994. “That’s because the production cars (on which race cars are roughly based) were getting aerodynamic for fuel economy. The tops of them were getting more rounded like the surface of airplane wings. That caused cars to generate lift when the air went over the top in a sideways or backward direction. We had to disrupt that air flow to keep the cars grounded.”

After the 1993 season—marked by Wallace’s two high-flying crashes and one by Johnny Benson at Michigan—Nelson, engineers from Roush Fenway Racing and former driver/crew chief/innovator Norman Negre (son of long-time racer Ed Negre) addressed the problem.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos