Ship Happens: How the Golden Ray's Final Voyage Went Wrong in a Hurry

From the April 2021 issue of Car and Driver.

The busy season on Saint Simons Island, Georgia, typically runs from Memorial Day to Labor Day. But 2020's tourist boom lasted well into November. A short detour off I-95, about halfway between Savannah and Jacksonville, St. Simons Island is known for golf and saltwater-based leisure pursuits. On one clear and breezy late-fall afternoon, people seeking a reprieve from their couches cruised the palm-tree-lined high street on foot or bikes; others sat on benches licking soft serve while staring at the fishing trawlers and cargo ships in the distance. The lower the sun dipped on the horizon, the more people drifted to the pier in pursuit of the perfect sunset snap. And amid all the smiles and poses, no one seemed to mind the giant shipwreck lurking in the background. If anything, they huddled closer together to keep the beached metal whale in frame.

Before it capsized, the MV Golden Ray shuttled cars through the auto industry's global supply chain for two years, leading a nondescript existence in the world of modern shipping operations. More than two football fields long and 17 stories tall, this roll-on/roll-off vehicle transporter makes your double-decker pontoon boat look like a bath toy. With its massive 17,335-hp 5522-liter two-stroke diesel inline-seven turning at a relatively lazy (for this magazine, anyway) 77 rpm, the Hyundai Glovis–owned ship plied the seas at a max speed of 20 knots (23 mph).

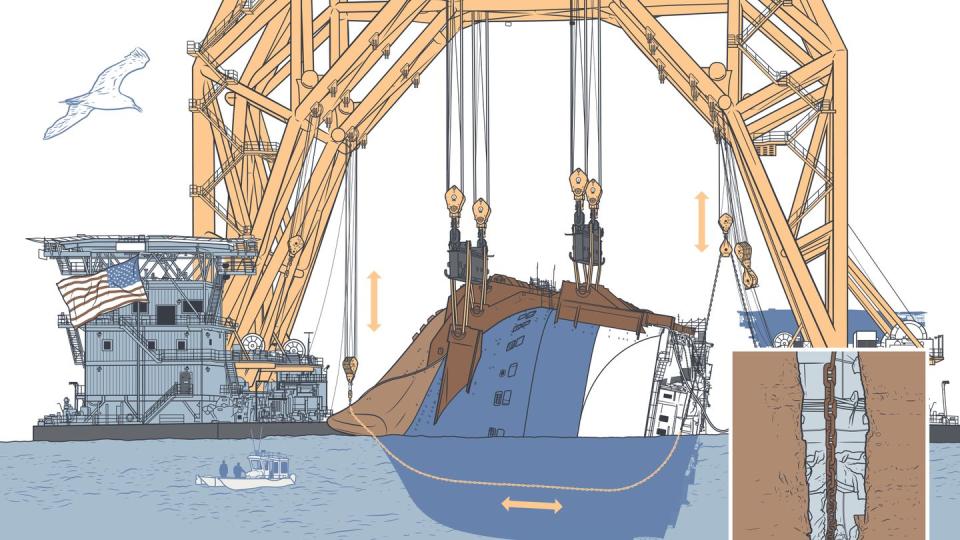

In September 2019, the Golden Ray departed the Port of Brunswick, Georgia, with a haul of about 4200 vehicles and soon developed a catastrophic list. The floating parking garage, with space for up to 7742 vehicles, tipped onto its side and beached itself just off the St. Simons Island shoreline. Nineteen months later, the Golden Ray's journey is finally nearing its end. This is the story, reconstructed from interviews and a multiagency investigative hearing conducted last September, of how a laden ship weighing approximately 38,600 tons lost its balance, became a gapers'-block tourist attraction on the Georgia coast, and launched a salvage effort that makes crushing cars look like child's play.

Even with Hurricane Dorian bearing down on Florida, the Golden Ray's final voyage was poised to be like any other assignment for the 23 Korean and Filipino seafarers serving in the ship's complement. The monthslong itinerary had the ship sailing from the Gulf of Mexico, up the Eastern Seaboard, and on to the Middle East. To avoid the storm, the Golden Ray treaded water after leaving Freeport, Texas, to slow its arrival to Brunswick, the nation's sixth-busiest auto port and an essential distribution outlet for the Hyundai factory in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Kia plant in West Point, Georgia.

On September 7, 2019, the Golden Ray eased into the harbor, where stevedores offloaded 285 Hyundai Accents and Kia Fortes from two decks and loaded 339 brand-new Kia Tellurides onto three. Harbor pilot Jonathan Tennant then joined the crew to navigate the boat out of the narrow shipping channel. Around 12:45 a.m. the next day, the Golden Ray raised its 275-ton stern ramp, and captain Gi Hak Lee declared it "ready for sea" and the voyage to Baltimore. Flanked by the Dorothy Moran tugboat, the Golden Ray made for the Atlantic with Tennant giving commands to the quartermaster at its helm. "Our job is very much about feel," he says. "You become in sync with the vessel." It was a still, 72-degree morning—"cupcake conditions," Tennant says. He remembers looking out at the moon, the lighthouse on St. Simons Island, and the lights on the Emerald Ace, an inbound car carrier. Once he felt in control of the vessel, he dismissed his tug so it could assist the Ace and pressed on, eventually ordering 10 degrees of starboard rudder to make the fourth turn of the voyage out to sea. But 10 degrees wasn't enough, so Tennant called for the next logical thing: 20 degrees starboard. That's when the ship began to lose it.

It was normal for the Golden Ray to lean while making the turn, but this "felt like she was going to spin out of control," says Tennant. Trying to slow the swing, he immediately called for midships (0 degrees), then 20 degrees port, then hard to port. When the ship didn't respond, he turned to Lee and asked, "What is happening?" Lee's reply—"Whoa!"—prompted Tennant to ease off a bit, to 20 degrees port. Suddenly, the ship's stern slid out "like someone kicking a stool out from under you," Tennant recalls. "The lights were gone. All I saw was water." Nevertheless, he kept driving, calling for full lock again, still hoping to right the ship. But unbeknownst to him, the rudder and propeller were already out of the water. Nothing could stop the Golden Ray from plowing into the sound.

The crash threw Tennant against the wheelhouse windshield, and he held fast to a gyrocompass to keep from sliding away. Water rushed into the vessel through an open door in the hull. Inside the upended engine room, engineers similarly clung to life in the dark as the seven-cylinder lost power and fires broke out across the disabled ship. With the stern stuck out in deep water, a flotilla of tugs and taxis responding to Tennant's distress calls converged on the capsized carrier to shove it onto a sandbar. The Golden Ray risked being dragged to the bottom of the channel, which could have choked off the busy shipping lane and drowned everyone aboard. Tennant is an Eagle Scout who still lives by the preparedness mindset at age 46. As he dangled 50 feet in the air, he thought about the rappelling gear in his work-issued F-250 Super Duty that was parked a half-mile away near the pier.

U.S. Coast Guard teams arrived by air and sea to contain the ship's fires and help Tennant, Lee, and 18 others escape. (True to maritime tradition, the captain refused to abandon ship before all members of his crew were safe, but Tennant convinced Lee he'd have a better chance of saving his men by leaving the vessel. That way, he could share his knowledge of the Golden Ray's access points with the Coast Guard.) Trapped in the bowels of the ship, four engineers stripped down to their underwear and climbed into the floodwaters seeking relief from air temperatures that hit an estimated 150 degrees. They banged on the hull to make their presence known. Nearly 36 hours after the accident, they were rescued through a hole cut in the hull. Tennant shudders to think what the outcome might've been had the ship rolled over at sea. "I don't believe there would've been any witness to it happening," he says. "And the ability to call for help would not have been there. I truly think that I essentially witnessed a miracle."

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos