Shops We Love: Car Conjurer

"In the early days, we’d be working on our own cars until Thursday afternoon,” remembers Dick Crosthwaite, carefully closing a Bugatti Type 35’s right-side engine cover with the ease that comes from having done something thousands of times. “Then we’d realize we needed a few quid to buy some cornflakes, so we ought to get busy with some customer jobs.”

This story originally appeared in the May, 2018 issue of R&T - Ed.

Things have changed a bit in the intervening half century. Type 35 Bugattis like the one Crosthwaite bought for £150 are now worth seven figures, and his shop, Crosthwaite & Gardiner, is in such demand that there’s precious little time for toys. Maybe that’s why Crosthwaite’s E-type has been almost finished since 1973.

You may not know of C&G, but if you’ve been to Goodwood Revival or the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, you’ve almost certainly seen-or heard-its handiwork. Whether it’s a simple driveshaft joint or a complete, from-scratch replica of an Auto Union grand-prix car, C&G can do it, and to a quality that has the world’s leading restorers and, more recently, OEMs beating a path to their door.

That door isn’t easy to find. Even as you enter the parking area next to the warren of C&G’s folksy farm buildings in Sussex, 50 miles south of London, there’s not much to give it away. No big signs, no parking lot littered with historic race machinery.

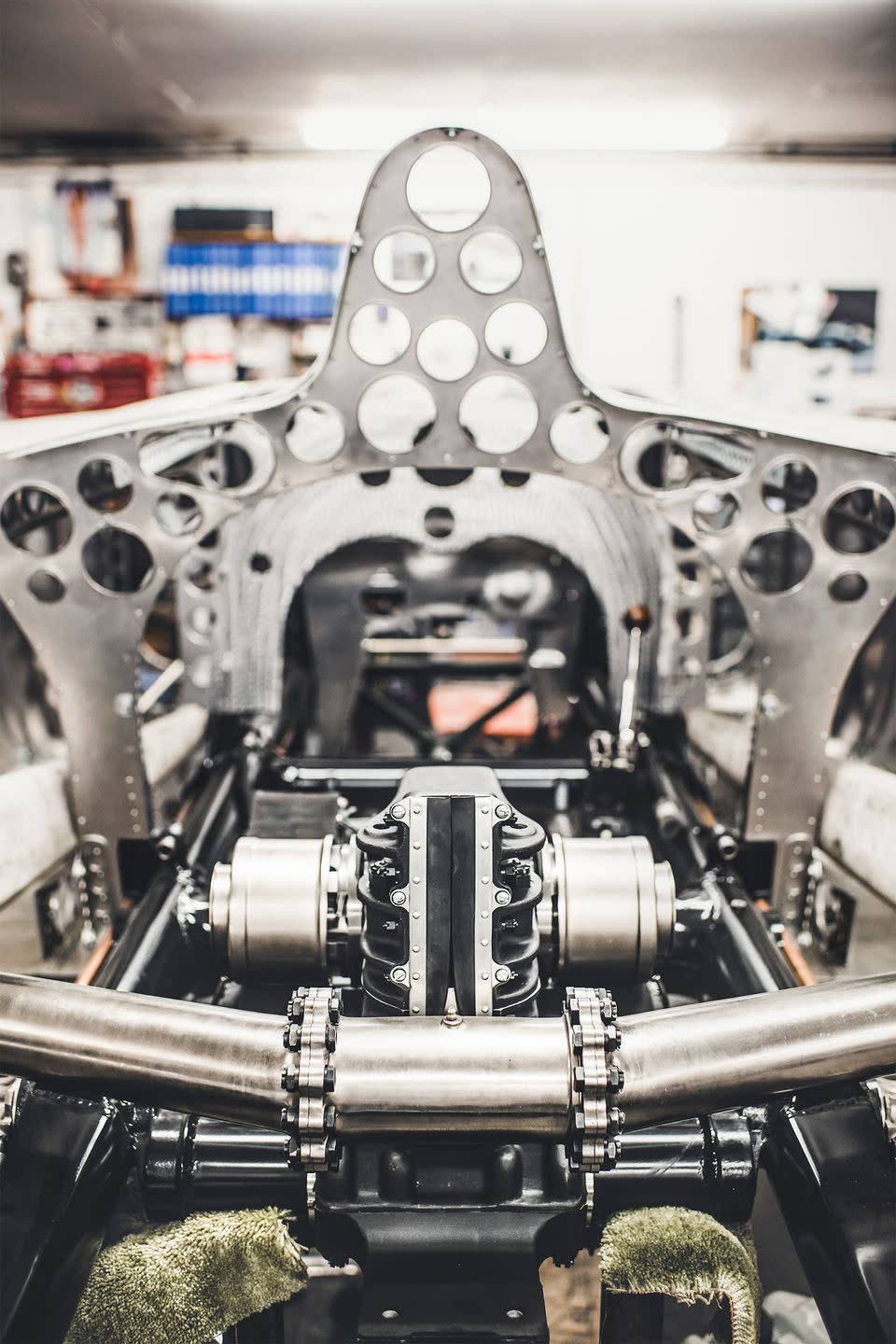

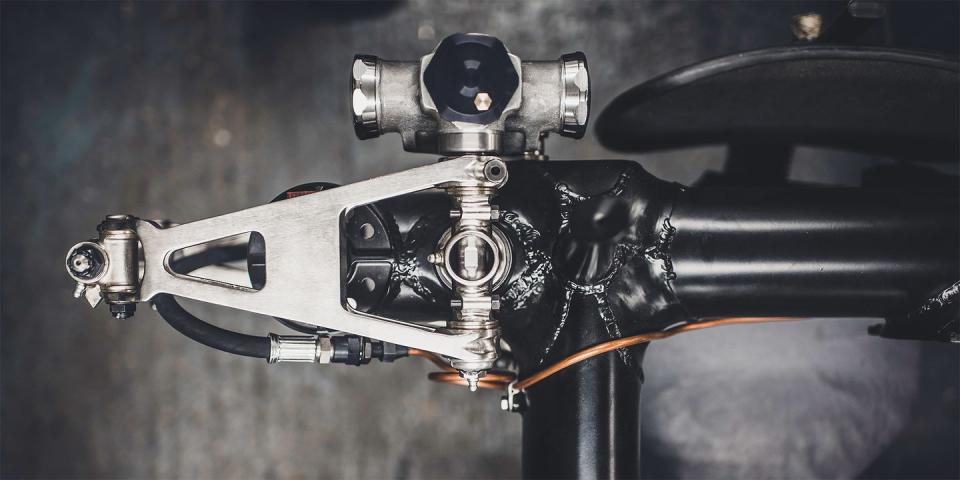

Inside, it’s a different story. First come the visual clues: the Norton Manx race bike, walls adorned with vintage photographs, and the exquisite Auto Union gearshift setup in the bijou reception.

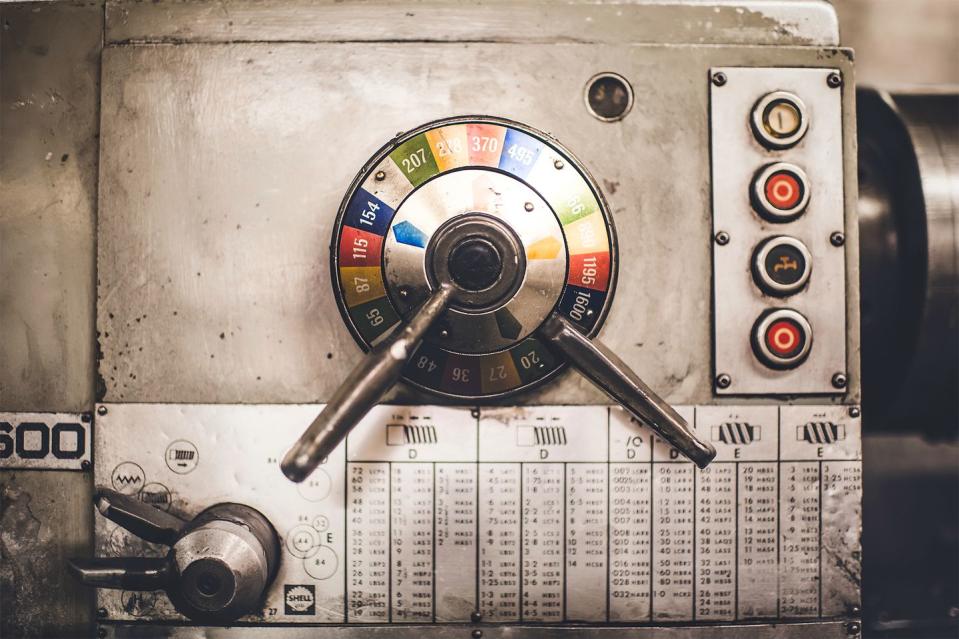

Then you step onto the shop floor and experience sensory overload. It’s dark and appealingly grubby. There’s the sound of machine tools, the bustle of knowledgeable-looking men in blue coats, and the patina that characterizes great old shops. But it’s the aroma, that unmistakable confection of oil, metal, and cutting fluid, that knocks you sideways.

This must be how shops looked, how they smelled, how they sounded in the 1960s, when Dick Crosthwaite and John Gardiner bonded over a shared love of old Bugattis and historic racing.

“There’s always been a historic-motorsport scene,” Crosthwaite says. “As soon as the cars were obsolete, people were buying them up to race them again. But there were only about three meetings a year in England back in the Sixties. These days, you could race every weekend.”

Crosthwaite was good at working the front of house and on the restoration side, making use of his encyclopedic knowledge of cars. Gardiner was the manufacturing genius and a brilliant toolmaker who dealt with the money. Gardiner succumbed to cancer a decade ago. The name remains, but in reality, it’s Crosthwaite & Crosthwaite, Gardiner’s share having been bought out by Crosthwaite’s son, Ollie, an accomplished toolmaker in his own right. He’s the managing director and has been instrumental in helping C&G adopt the latest and best technology available to evolve a business that started as a restoration shop but is now firmly focused on making parts that restoration shops can’t operate without.

“We have a lot of original [drawings and blueprints], but we redraw everything. We computer model it, using the latest technology,” Ollie Crosthwaite explains, showing me a laser scanner. “We’ve got three people just doing engineering drawings. It’s a big part of what we do.”

Out in the shop, beyond the traditional mills and drills, there’s a brace of huge, computer-controlled milling machines. One is working on a 3.4-liter straight-six XK block, one of C&G’s specialties. The firm is known to have supplied its 100-pound-lighter aluminum blocks to Jaguar for the marque’s lightweight continuation E-types, though Ollie Crosthwaite is too discreet to brag about it. The mills’ software alone costs some $35,000 and the hardware 10 times that, but he’s convinced the jump in quality is worth it.

“Sometimes we look at some of the parts that are 25 years old, and we end up chucking them away because they’re not up to the quality we sell now,” he says.

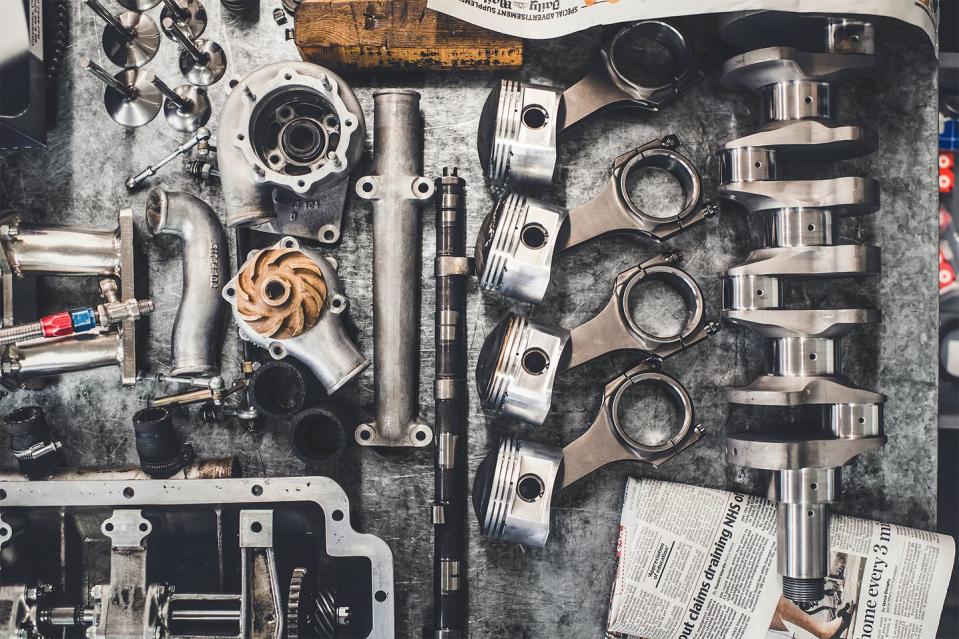

Evidence of that quality is everywhere: wide-angle Jaguar D-type cylinder heads with their valve-guide bosses machined flush to maximize flow; a cush drive for a grand-prix Mercedes-Benz supercharger that’s far too beautiful to be hidden away; and, in a separate room, behind trays and trays of small but expertly machined bolts and brackets, new-old-stock Bugatti parts Dick Crosthwaite picked up from the factory in Molsheim, France, decades ago.

Then there’s a perfectly re-created magnesium wheel for a Porsche 917K sitting upturned without a tire, 19 inches deep and looking like the world’s most beautiful trash can. Wheels are big business at C&G. Why risk ruining a set of originals racing, and who wants to take a chance doing 200 mph on 50-year-old rims anyway? Better to store them carefully and let exquisite replicas take the strain.

The difficulty in finding people willing to part with original vehicles, even with bank-vault quantities of cash on the table, means a ground-up replica build is often the only solution. As was the case with the complete Auto Union grand-prix cars C&G built for Audi and the series of W125 Mercedes racers commissioned by a U.K. construction tycoon.

“We like a challenge,” Ollie Crosthwaite says, smiling. To find a few of these projects, we climb some stairs, swapping the noise and darkness of the engineering area for the wide-open spaces of the calm, daylight-infused engine-assembly room. A pair of race-ready Coventry Climax engines sits next to a partly assembled XK six. At the far end, there’s the brass cylinder head and associated parts that make up the heart of an early Bugatti. That’s the bread and butter. The real buzz is the re-created roller-bearing cranks used on Porsche’s four-cam, four-cylinder engines and, lurking under a sheet, something intriguing for a major European OEM that the shop can’t reveal but promises we’ll hear about soon.

Downstairs, Dick Crosthwaite is making soup for us in the café he recently installed in his private garage area of the shop. He tells comical anecdotes about months spent jetting around the world helping Ralph Lauren buy the cars that make up his legendary collection. And the time in late-1960s London when racing friends Frank Williams and Anthony “Bubbles” Horsley built an entire Cooper F3 car in an upstairs room. It later proved impossible to extract through the window.

Dick Crosthwaite could have stepped back from the business by now, but the 10 minutes he spends studiously removing the luggage area and carpet in the rear of his Frazer Nash to show me its incredible chain-drive setup proves that he’s not lost the enthusiasm. Maybe he’ll get that E-Type finished this year. Apparently there’s only some wiring work left to do.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos