How 'Need For Speed' Became the World's Biggest Racing Game

Senior feature editor Doug Kott takes the Porsche 911 hot into a corner and lifts off the gas. The 911 starts to rotate, the rear-engine performance icon’s trademark liftoff oversteer snapping the back end around. Two and a half decades later, he still recalls being stunned by that moment.

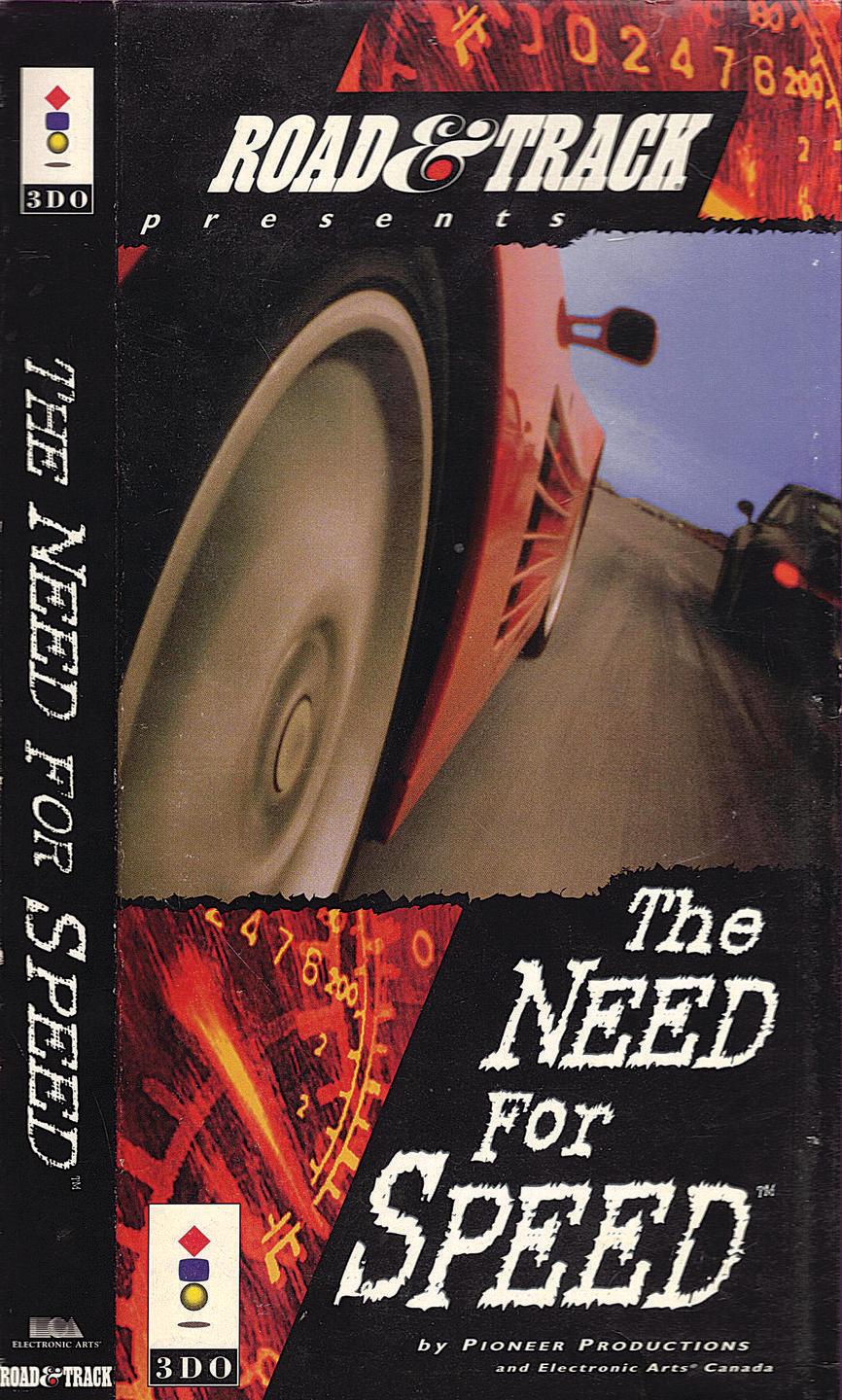

Kott wasn’t on a racetrack. He was in his Newport Beach office playing a beta version of what would become Road & Track Presents: The Need For Speed. And for the first time in his life, he was seeing a digital car, rendered on the cutting-edge 3DO game console, behave like its real-life counterpart.

That Kott was the one testing it was no coincidence. The market was full of simple racing games, unsophisticated stuff paying little mind to how real cars behaved. Hanno Lemke, the producer behind The Need For Speed, wanted to make a driving game that immersed you in the perfect drive, that gave you a window into what the best road cars could actually do, and how.

“We wanted you to smell the leather, hear the gated shifter and all the unique sounds of the engines,” Lemke said. “We wanted the experience to be what it might be like for the player to have the keys to that car for a day.”

That degree of authenticity required lots of performance data, detailed drive impressions of the cars themselves, and ample feedback on the virtual cars developed for the game. So Lemke and his team from game studio Electronic Arts approached Road & Track, hoping to use the magazine’s name to bestow credibility on the fledgling series, and the staff to fine-tune the game.

Road & Track sent photography assets, testing data, and detailed drive impressions on cars such as the Porsche 911 and Lamborghini Diablo to EA. Editors were required to put in a minimum number of hours on beta versions of the game. EA used the feedback to instill the digital cars with the personalities and qualities that defined their metal-and-leather counterparts.

The game grew to encompass more than just Road & Track. After its well-received release on the niche 3DO platform, The Need For Speed was ported to MS-DOS, PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and Microsoft Windows. Sequels included blockbuster hits like Need For Speed III: Hot Pursuit; Need For Speed: Underground; and Need For Speed: Most Wanted. And though its tie-in with Road & Track ended after the original game, the missions and attitudes of the two brands moved in the same direction.

“Our goal was with each iteration to create a different story, a different experience for players while retaining the core tenets of the franchise. Which were real cars, car culture, car passion... It’s about the experience, not just about who’s the fastest around the track,” said Lemke, who shepherded the series through 2007’s ProStreet.

The game series was defined by this appetite for change. Its domain encompassed car culture, whatever form that might take. At the outset, NFS focused mostly on supercars and open-road drives, sending players in Ferraris and Lamborghinis down incredible coastal highways. But as the audience got younger, and the supercars looked less and less attainable, Lemke wanted to meet enthusiasts where they were. The pop-culture presence of tuner cars and modification was booming, evoking a rebellious counterculture of rowdy driving, sideshows, and bold music.

The 2003 release of Need For Speed: Underground dove into this, bringing the late-night racing of slammed Civics, boosted S2000s, and tuned Integras to the forefront. Supercars and proper racetracks were intentionally absent; the game was about regular roads, Dodge Neons, and Ford Focuses.

Not satisfied with making supercars feel accessible to players, Need For Speed set out to prove that the car you already owned could be a hero. It was a statement that the love of cars didn’t require six-figure investments or private racetracks. All it took was a willing driver and a place where they could drive fast, consequence-free.

That resonated. With the release of Underground, Need For Speed went from an enthusiast favorite to a cultural phenomenon. Around seven million copies were sold in the game’s first six months, with total sales eventually reaching 15 million. It became one of the best-selling games on PlayStation 2 and launched the series on its path to becoming one of the all-time most successful franchises. That single title accounts for nearly 10 percent of the sales of the entire 24-game Need For Speed franchise and stands as the first true culture-defining hit of the street-racing genre. Underground’s focus on customization, driving culture, and accessibility became hallmarks of the series.

“The way we think about it now, Need For Speed is self-expression. In a slightly more nuanced way than how it always was, either that vehicle is aspirational and says something about me or my connection to that vehicle says something about me,” says Matt Webster, who as vice president and general manager of Criterion Games oversees the development of new NFS titles. “Because it’s weird to think about this collection of engineering bits and bolts having a soul, but we talk about it all the time. And that’s because there’s a strange connection between humans and motor vehicles, I think, and one that’s very personal. The game reflects that.”

Every aspect of the series is centered around building and maintaining that connection. Expressive soundtracks of new music became a staple of the series. EA ditched blended-in background music—a hallmark of games like Forza and Gran Turismo—in favor of stuff you’d actually listen to while driving. Hip-hop, hard rock, and metal tracks from real artists brought life to the world, with EA even bringing in big-name artists like Jamiroquai to promote the game. The music, far from being a mere afterthought, was central to the experience.

Cars, significantly, would never be mere commodities. The team fought hard to avoid the paradox of choice, where overwhelming options prevent satisfaction with a decision. They were intentional and ruthless in trimming down the car list for every game, making sure it never became the bloated, 700-car mess that is the Forza menu. With a field that crowded, the machines begin to seem interchangeable and disposable. Variety retained its importance—the game needed a few dozen cars to cover tuner options, supercars, sleepers, and classics—but every car had to be memorable, a character in its own right. “The car is at the center, but it’s a human story,” Webster said.

The best expression of this ethos came with 2005’s Most Wanted, a megahit that sold 16 million copies, making it history’s best-selling real-life racing game. The car list included only 32 models, but the story brought players into direct competition with tricked-out, liveried versions of the “most wanted” villain cars, fighting for pinks and a chance to drive them yourself. Forget the enemy drivers; the opposition cars themselves were sinister, aggressive, well-defined villains. The blue-and-white E46 BMW M3 GTR in particular was so iconic that fans still recreate the livery in real life.

A decade and a half later, Need For Speed has struggled to reach its former heights. The post-Most Wanted games still sold in the millions, but Lemke notes that the yearly release schedule didn’t mesh well with the complexity of modern games. Other yearly game series, such as Call Of Duty, have multiple development teams in different studios, allowing each team to work for three years to deliver a fleshed-out product while publishers enjoy the relevance and added profits of a yearly release. With a small team, it got harder and harder to keep up with the calendar.

Carbon, the follow-up to Most Wanted, mustered fewer than a quarter of that game’s sales. ProStreet did even worse. The 2010 relaunch of Hot Pursuit brought some life back, but ultimately the 2006-2018 era of Need For Speed was a series of disappointments. From the series reboot, simply titled Need For Speed, to the micro-transaction-filled Payback, the games—developed by Ghost Games during this time—never reached the same heights as the greatest hits.

NFS Heat, the final release by Ghost Games, recaptured some of the magic. Its neon-infused Miami Vice aesthetic and modified Polestar 1 cover car signaled the series’ return to the silliness and creativity that made it a hit. The game allows you to flip between sanctioned road-course racing during the daytime and ditch-the-cops action by night, with a narrative story punctuated by billboard-busting fun. It’s inspired by what Webster calls “the innate stupidity” that we love in cars, the sheer absurdity of setting loose a pack of two-ton controlled-explosion machines on public roads. It is neither the most realistic nor the most precise driving game on sale. It is easily the most fun.

People who just love cars, Webster admits, will likely reach for Gran Turismo and Forza. That will always be a powerful niche. But a much larger group has been brought in by the ongoing boom of the gaming industry, players who love games but haven’t yet fallen for cars. To Webster, Need For Speed’s role is to bring them in, to show them what a great driving experience really feels like. It’s not about the fastest lap time or the most expensive ride. It’s about proving that cars can be so much more than soulless hunks of metal.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos